Fidelio: Love & Liberation in the 20th Century

At this time of year spirits can be low, and just as the cold weather was starting to creep into my soul, I attended Fidelio, the Canadian Opera Company's first production of 2009. This fierce tale of romantic heroism, beautifully presented by some of the company's top vocal talents, served to warm my winter-addled heart.

As Beethoven's only opera, Fidelio is a unique experience in and of itself, and the COC co-production with the Opera National du Rhin and Staatstheater Nurnberg was no exception. Presented in the political light of early 20th century Germany, punctuated with Kafka epigraphs, and set in the oppressive confines of a Spanish prison, I wasn't sure whether the love story would shine through the production slant; but to my delight, I found the performance was profoundly romantic, showing how love and loyalty triumph in even the coldest of circumstances.

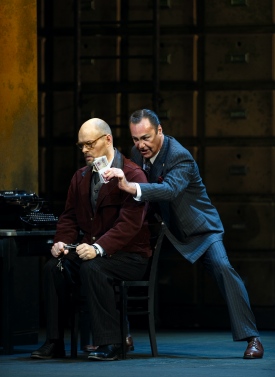

Returning to the COC stage for another flawless performance as Marzelline was Virginia Hatfield, the former COC Ensemble soprano who I recently saw in Don Giovani. But the most memorable vocal performance was that of Gidon Saks playing Don Pizarro - the cruel magistrate who has run the jail into corruption. Not only does his liquid baritone rise above the rest of the cast, but the passion and anger with which he delivers his presence to the stage is tangible.

Less tangible, and frankly somewhat disappointing, was the lead Leonore/Fidelio, played by Adrianne Pieczonka. Though her voice is absolutely beautiful and technically exact, she was not an ideal choice for this role. A fellow blogTO reader, Cavan Campbell, seemed to agree with me (quite eloquently): "She gave me no sense of the conflict in Leonore, no sense of strong desire, and there was a total absence of duality in her performance. She's leading a double life in the most extreme sense, hiding her own gender, and yet she gives off no sense of doubt in her performance. She just seemed to skip through every scene, as if her body, her face, her arms and legs were only place-holders for the voice, merely walking her set of lips from song to song."

Though it can sometimes seem that opera ignores the dramatic accoutrements of theatre, the set was one of the more striking features of this production. Set in a very modernist-looking prison, the walls of the stage were lined from floor to ceiling with filing cabinets, adorned with industrial desk lamps and accompanied by a large steel door. The bureaucratic efficiency and mechanization of the German work ethic seemed echoed in the characters' surroundings, and impressed the feeling of confinement on not only the prisoners, but also the prison employees working under Don Pizarro.

Less impressive was the jail cell used to hold Fidelio's husband, Florestan, which was some sort of laundry pit reminiscent of the garbage compactor in Star Wars (above). It seemed incongruous to the otherwise clever set design, and ultimately didn't give the oppressive feeling I got from the pillars of sky-high filing cabinetry.

One of the most memorable scenes came in the first act, where prisoners were shown to be desperately reaching for civilian clothing suspended high out of reach (top). The prison detainees were an integral part of the opera, being moved around in shackles and coming on and off set at the whim of the guards. The hopeless deterioration of these men within corrupt institutional confines is constantly juxtaposed against brief glimpses of the outside world - such as a shaft of natural light piercing through the filing room, or a blue sky peeking out from behind the steel door left ajar - which poignantly disrupt the despair of their situation.

Also worth noting is that although the story takes place in a Spanish prison near Seville, the German libretto and obvious 20th century symbolism suggests Nazi-undertones to the character of Don Pizarro and his assistant Rocco, who 'just follows orders'. The tension created by implying a connection between the corruption at the jail and the Nazi movement is undeniably present, if not entirely clear.

Despite some puzzling attributes, the love between Leonore/Fidelio and her husband Forestan does shine through in the production, and the final scene is an extremely emotional culmination. While the prisoners are being freed from Don Pizzaro's tyranny, Florestan is at last unshackled as the entire chorus sings the praise of Leonore, and of her loyalty and heroism as a dutiful wife. Not exactly a modern romance, but a true celebration of liberation and love in a more desperate time.

Next up is Rusalka, another love story but somewhat on the steamy side, which opened just last week at the Four Seasons. The COC seems to be setting me up for a winter love affair, and I'm looking forward to more heart-warming performances, complimented by world class vocal and instrumental talents.

Photos by Michael Cooper

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments