The End of Kodachrome and the Death of Kodak Heights

Last week's announcement by Kodak that they were discontinuing their iconic Kodachrome slide film made me wonder what's become of the Kodak lands where their Canadian factory stood for 80 years. The disappearance of Kodachrome is just one more milestone in the end of the film era of photographic history, but for me, the closure and demolition of Kodak's Mount Dennis plant four years ago was the one that rang the death knell resoundingly.

There's nothing left of the Mount Dennis plant but Building 9, though that might not be the case for much longer - the former home of Kodak's employee centre is a derelict hulk, open to the elements and the depredations of local kids who've smashed nearly everything breakable and covered the walls with graffiti tags. Metrus Properties, the developer who demolished the plant two years ago, has obviously put the preservation of the sole remnant of what was once called Kodak Heights at the bottom of their list of priorities, and it's hard to imagine it still being around when Metrus - or anyone - finally gets around to breaking ground.

Kodak literally made Mount Dennis - the aerial photo above (Building 9 is shaded with green) shows Kodak Heights in 1930, a few years after my mother began working there. The neighbourhood grew to provide places for employees of Kodak - and CCM and Heintzman and Willys Overland, to name a few of the industries to the north and south in Weston and the Junction - to live. Weston Road on either side of Eglinton thrived with Kodak's fortunes - so much so that the company's decision to cut the lunch break to half an hour in the '70s is still considered the fatal blow that gutted the street's merchant life.

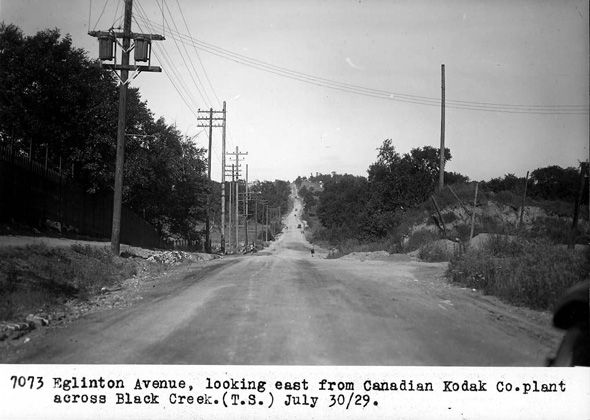

From the air, Kodak and Mount Dennis seem prosperous, but look at the vast expanse of woodland, farm and pasture to the north and east, or this photo, taken at the same time, of Eglinton Avenue looking east - a rural road that actually ended a few hundred yards to the west, just before Jane Street. This is the Kodak where my mother worked, and the Mount Dennis where she lived - a self-contained, working class "unplanned suburb" that had changed a lot before I was born, by which time Eglinton was a paved thoroughfare that roared through the neighbourhood.

Kodak prospered the whole time, and by the time my mother had left to raise a family, my cousin had begun her long career with the company, and my sister would later work summer jobs at the plant. Employment reached a peak of over 3,000 in the '70s, but had fallen to just 800 when Kodak Heights finally closed in 2005, an obsolete legacy that the company had to shed to survive in the digital age. While I can understand why Kodak Heights couldn't survive, it's still hard to suppress sadness and even anger when I approach Building 9 from Photography Drive.

Two years ago, I was aiming my camera through the fence to shoot the machines tearing down the plant; today I can just step over the fence and walk out into the wasteland around Building 9. Kodak's imposing presence in Mount Dennis still lingers enough to make me wonder that it's disappeared so completely. Besides Building 9, the only remnant is the burned-out security checkpoint by Industry Drive, and the massive pylon for the backlit Kodak billboard that faced Black Creek Drive.

Building 9 has become a destination for camera-toting urban archaeologists, and their photos from just the past few months reveal how quickly the building is being destroyed. As I walk through the side door to the auditorium/gymnasium that was added to the rear of the building in the '30s, I can't help but remember that the last time I was here was almost a decade ago, when I was given a tour of the plant while writing a feature on Mount Dennis for Toronto Life. The gym was filled with rows of chairs facing a screen, in preparation for a company address to the employees, most of whom already knew that time was running out at Kodak Heights. I illustrated that article with a film camera; it seems like so long ago.

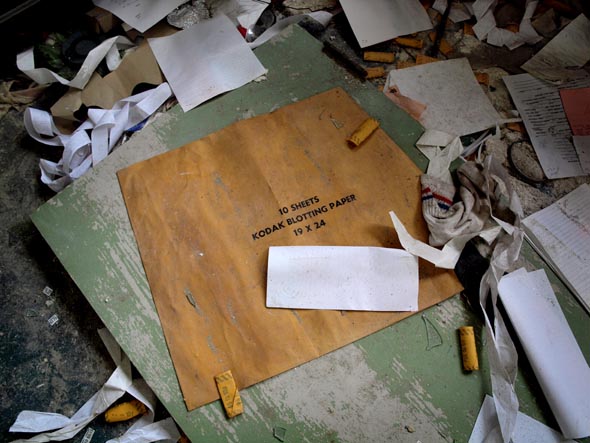

Upstairs, the offices have been trashed, sheer curtains sway in the breeze through broken windows, and the soggy pulp of broken ceiling tiles melt into torn carpets. My search for some Kodak artifact is finally rewarded by what's left of the camera club darkrooms - a package of blotting paper for drying prints. Downstairs, the lobby floor is covered with broken glass and shards from the shattered art deco chandeliers that once lit the sweeping staircase. I imagine my mom, an irrepressibly sociable woman, hurrying up the stairs to some company function, an image that becomes more vivid later that night, when I find this heartbreaking photo of the lobby from a 1942 employee's guidebook.

I understand completely why Kodak, eager to avoid the fate of its onetime rival, Polaroid, had to make drastic decisions such as the one to close Kodak Heights. I can also understand why local residents and politicians are pressuring Metrus Properties to try and replace the industrial jobs the area has lost, instead of filling the Kodak lands with big box retail stores. I can even understand why bored local kids are trashing Building 9 - frankly, I might have been one of them if this had happened 30 years ago. What I can't understand is how no one can see the value of Building 9, even if just as a reminder of when even blue collar life had its touches of elegance, but I'm sure my dismay is largely a personal reaction to what seems like the erasure of all that history, much of it my own.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments