Harolding in Mount Pleasant Cemetery

Harolding, if you've never encountered the term, involves spending one's time hanging around cemeteries taking in the ceremony of death — or at least soaking up the solemnity of what we like to call a place of rest. A neologism seemingly made for the Urban Dictionary, the term's etymology derives from the 1970s cult film Harold and Maude in which the protagonist's obsession with death leads him to frequent graveyards and attend the funerals of strangers (amongst other dark and moody activities).

Having missed out on the film until later in life, my initial exposure to the term came courtesy of Douglas Coupland's 1996 collection of non-fiction Polaroids from the Dead, in which he shares his youthful experience harolding in B.C.'s Capilano View Cemetery.

Reading that narrative, I realized that, for better or worse, harolding was something that I'd been doing for some time.

It started when I was given my first real bike. A snot-green Fuji with 21 gears, my mother thought that a little indulgence on this purchase might keep my activities clean over the impending — and my first — unregimented summer. Less a gift than an unspoken promise, the purchase of this bike was a pact between the two of us that I would keep my hands firmly affixed to the handlebars and not upon whatever other trouble presented itself.

So, as my friends headed north to summer camps, I was left city-bound and primed to explore the world at my wheels, the Toronto of a 12-year-old.

Living at Yonge and Davisville at the time — and having a relatively limited geographic range — I was drawn to Mt. Pleasant Cemetery. Its many turns and undulations were the thing that would, to some extent, make the pact stick: where else could you ride like this?

I spent the entire summer in the cemetery that year, getting to know more than just its roads. While it might seem odd now — all those dead people in the ground, so close! — this was a remarkable place to explore at such a tender age. From my early discovery of the Eaton family mausoleum to my later location of an entrance to the neighbouring ravine, the cemetery always felt like a place that was at once mysterious and welcoming.

But, of course, there was also the occasional funeral.

One doesn't spend so much time in a graveyard without encountering a few of these silence-inducing ceremonies. The first time I happened upon one, the carefree "park" that I had become accustomed to ceased to exist.

The final resting place of more than 168,000 people, I now find it rather remarkable that I had been so cavalier about treading its grounds. Although I had spent day after day there, I wasn't really a harold so much as an obtuse pre-teen.

But even after witnessing the act of mourning a few times, I continued to return to Mt. Pleasant Cemetery. And though I still stuck mostly to the roads, refusing to get off my bike and explore the areas off the beaten-track, I began to take notice of the tombstones.

I had always been aware of them in some vague sense, but I had never paid them any focused attention. So as the summer neared its end, I started reading the epitaphs. Still so young, I'm quite sure that was, to a great extent, clueless to the gravity of these inscriptions — and yet I was obviously intrigued by them in some way that's still difficult to explain.

As school resumed, I frequented the cemetery much less. Not only was I occupied by activities with my friends — none of whom were big cemetery-dwellers — but that entrance to the ravine I had found led to an obsession with mountain biking that would turn me off paved roads in general.

It was not until many years later that I returned to Mt. Pleasant Cemetery. I was in grad school and living on Woodlawn Avenue at the time. Suffering from bouts of anxiety (so much Nietzsche, so much angst), I would walk in the ravine near my apartment in an attempt to manage stress. On one such walk, I found myself at the ravine entrance to the cemetery that I'd discovered so long ago.

Walking around the place as an adult was a profoundly different experience. Both familiar geographically and unfamiliar psychologically, the cemetery now engaged me as someone who spent a tad too much time considering my own mortality. But, being on foot, I only explored a small area of the grounds that day. This reacquaintance, however, lead me to return with a careful regularity. As much as I enjoyed my contemplative walks, I didn't want to indulge my harolding habit too much. Despite their calming effect, a looming depression seemed to hover whenever I spent significant amounts of time there.

So I spent the fall of that year studying modernist literature and harolding on the weekends. But, eventually this phase passed as well. Who knows if it was the onset of winter or simply the fact that I grew bored of my cemetery-dwelling — either way, it was once again a long time until I returned.

My latest visit to Mt. Pleasant cemetery was made primarliy so that I could finally come to terms with all the time that I'd spent there in the past. I happened to re-read Coupland's account of his harolding days, and decided that I wanted to take some of my own experiences down. Knowing that I would likely publish it here, I also decided that I would photograph the place for the first time.

This was far more difficult than I expected. As I drove along the roads I still knew so well, I was hesitant to get out of the car and reveal myself and my camera. As was the case when I came across that first funeral, I once again felt that I was an intruder. Although I had used the cemetery for years, I was struck by this feeling that it was a private place not meant for photographs.

Who were these people, after all? George Pears? Captain Fluke? Intriguing and mysterious are the lives behind these monuments, but also so distant. Surrounded by tombstones bearing the names of strangers, there was something alarmingly voyeuristic about the act of snapping away.

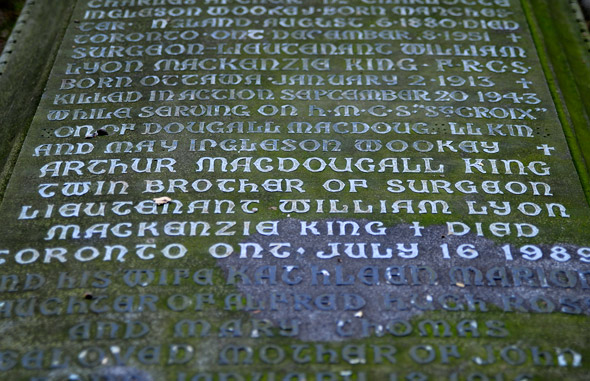

It was not until I stumbled upon the gravesite of former prime minister Mackenzie King that I started to become more comfortable with the camera in my hands. His grave is marked by an official government plaque and is obviously welcoming to member fo the public who wish to pay their respects.

While Mackenzie King's tomb can't be compared with Jim Morrison's, it nevertheless dawned on me that the majority of cemeteries aren't really private places at all. Sure, most are technically private properties that grant access to the public, but that technicality isn't altogether important here. No, what I'm driving at is the fact that they're places of commemoration. Perhaps this is an obvious observation, but as I was trying to shoot the tombstones and mausoleums that day, I felt it come upon me as something of an epiphany.

There will always be a discomfort in capturing, once again, what is a monument to fixity. But, that word — monument — it reveals so much. A tomb is a reminder, a record, a narrative condensed into a figure of the lived, now gone — but not forgotten when looked upon, when witnessed.

So I must cast out my shyness, this fear of the shutter-trips.

I'm here.

And the act of sharing is a testament not just to those interred at Mt. Pleasant Cemetery, but to memory itself.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments