The history of the Spadina Expressway debacle in Toronto

When I strolled recently through Cedarvale Park, it was hard for me to imagine that the leafy ravine was once destined to become polluted and congested with high-volume traffic.

But, despite how hard it is to picture today, this would have been reality if 1950s urban planners with a short-term vision for the city got their way.

Cedarvale is an early twentieth-century neighbourhood, built by Sir Henry Pellatt of the nearby Casa Loma, would most certainly have a completely different character should the Spadina Expressway have been built.

The Annex, along with parts of U of T's campus, would have also shared in this fate, and the Spadina Museum (next door to Casa Loma) would have been demolished.

Unfinished roadbed of the Spadina Expressway, 1971.

Many decades later, the Spadina Expressway controversy is a reminder of the post-war clash between the interests of inner-city dwellers and the values of suburbanites and of a redevelopment philosophy that could be summarized as "to hell with the old...bring on the new."

In The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, John Sewell, a former mayor of Toronto and one of the key activists in what became a grassroots movement against the highway, writes that as the former wanted to protect their neighbourhoods, the latter desired an easy access to downtown, where a vast majority of them worked.

Construction of the Spadina Expressway completed as far as Lawrence Avenue West, 1969.

Like elsewhere in North America, a good chunk of Toronto's middle class moved away from the inner city to the urban fringe and beyond, relying on cars to ferry them from their remotely located, under-serviced and often unsustainable, suburban communities.

These two opposing visions for the city were reflected in the Metro Council and the Toronto City Council. Not surprisingly, the suburban councillors were all much in favour of the highway, while the majority of the Toronto councillors opposed it.

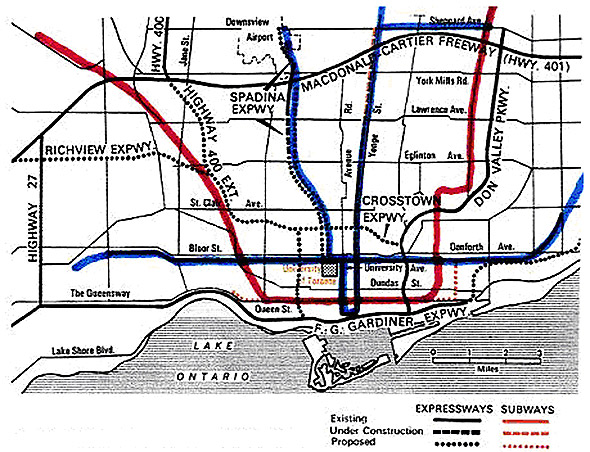

A map showing the proposed Spadina Expressway.

The Spadina Expressway was one of a series of planned highway routes for the city, which included a Highway 400 extension, Scarborough, and the Crosstown.

All of them were to culminate in the centre of the city. Nearly a thousand houses were to be demolished and in their place new parking lots were to be constructed.

To Sewell and others, this plan did not simply mean getting downtown faster; it was really a "remaking [of] the city in a radical fashion."

Those opposing the Spadina Expressway banded together in a coalition called Stop Spadina Save Our City Coordinating Committee (SSSOCCC).

It was organized in the 1960s by Alan Powell, a U of T professor, and its membership included Jane Jacobs (who resided in the Annex) as well as practically every social group who was affected by the potential appearance of the expressway.

The group lobbied powerfully for several years, organized demonstrations, crowded political meetings and researched links among various politicians to the highway.

The Spadina Expressway became the election issue in 1969, and Sewell, a member of the SSSOCCC, was elected to the Toronto City council.

In tune with other councillors who stood against the erection of the expressway, he vowed fiercely to continue to oppose the expressway at the Councils and to take the fight to the provincial government if necessary.

Residents protesting for completion of the Spadina Expressway.

The Spadina Expressway was fortunately never completed, and the part that did get built was renamed W. R. Allen Road.

However, before Bill Davis, the provincial premier, halted the construction in 1971, a giant ditch was dug up in the north end of Cedervale park, which served as a reminder of how closely it came to destroying the essence of the inner city.

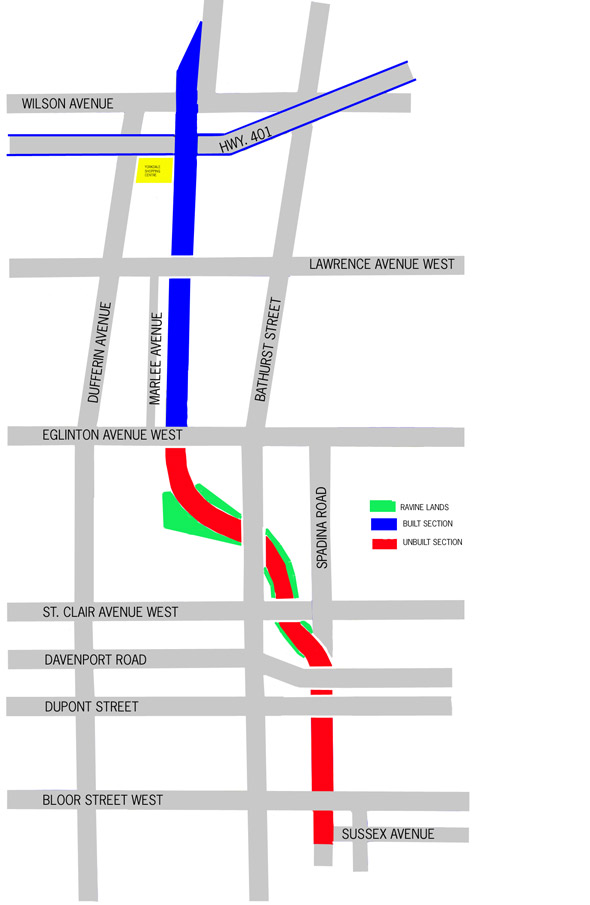

Map showing built and unbuilt sections of the Spadina Expressway.

Other bits of evidence of the planned expressway also remain elsewhere in the city. As Mark Osbaldeston notes in Unbuilt Toronto: A History of the City that Might Have Been, the facade of U of T's New College that faces Spadina is windowless (builders anticipated an ugly view).

Also, the lawn at the Toronto Archives sets the building far back from the street to accommodate the expressway that was thought to be coming and the Ben Nobelman Parkette just south of Allen Road's termination at Eglinton was built on land that had been acquired for the expressway's path south.

Dotted line shows the strip just below Eglinton Ave. that Premier Bill Davis gave the city to block extension of the Spadina expressway. The 3-foot by 750-foot strip runs from Winnett Ave. on the west to halfway between Strathearn and Flanders Rds.

In fact, in 1985 the province leased the city a three feet deep by 750 feet long tract of land in the same area just to ensure that Metro couldn't somehow find a way to continue with the highway.

This narrow strip serves as a mostly symbolic blockade, but an important one for those who cherish neighbourhoods like Cedervale and the Annex.

Toronto Library Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments