Future not so bright for laneway housing in Toronto

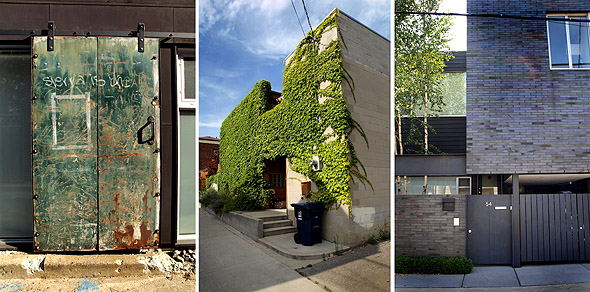

Toronto has miles of laneways, a parallel city just off the axis of our street grid, where garage doors replace porches and mailboxes. It's a place where glimpses of people are rare, though you'll occasionally find a house sprouting amidst the tarpaper siding and spalled brickwork, a lone colonist for human life in this city for cars.

Toronto's first laneways were laid out in the age of the horse, and you'll still find the odd coach house behind older streets, complete with second floors for hay storage. They spread with the auto, as the city's narrow residential lots made the street-facing garages commonplace in nearly every suburban subdivision impossible. They're traveled mostly by graffiti- taggers and stray cats, but some urban pioneers regard them as a wasted opportunity to increase urban density and add another layer to city life.

"It's unusual and that's very appealing," says architect Martin Kohn, who designed a laneway house on Croft Street, near College and Bathurst. "It's a different situation than normal and some people want to be different. There's an enforced modesty about your ambitions because the sites are so tight, and privacy issues and how you deal with those things. There is a virtue in restraint, and that appeals to people."

Croft is a unique exception to the city's laneways - a named street with stretches of housing built intermittently along its length. It's also the sort of place where laneway housing pioneers are more likely to overcome obstacles put in their way by the city's zoning laws and committees of adjustment. Kohn's firm is one of a handful that have made laneway housing a specialty, but he says that he strives to let potential clients know that they'll likely have an uphill battle getting their homes built.

"We get calls every six months, we'll get two or three phone calls people asking about it, and sometimes we'll even go look at properties. But in the end they've got to be really committed, and spend some money to push it along."

Meg Graham of Superkul Architects was the architect of a laneway house on Shaftesbury Avenue, near Yonge and Summerhill - another project that made it through city approval thanks to being sited on a named laneway where other homes already existed. Like Kohn's Croft street house, the home on Shaftesbury was built on the bones of a preexisting structure, and the architects were forced to be creative, both in satisfying myriad city requirements and applying for variances, and in maximizing the tight footprints of the sites. Echoing Kohn, she compares designing the house to building a boat, where every square foot has to be used.

But like everyone with a passion for laneway homes, Graham says that the city could be a lot more accommodating to these kinds of projects. "Policy always leads, right? And it's stated in the official plan that this increased level of density is desired. The zoning always takes a long time to catch up and there's always the NIMBY factor, too. Policy is a broad brushstroke instrument, and in the end people are going to be either really interested or completely uninterested in seeing it in their backyard."

The hurdles in building a laneway house are plentiful: besides getting services like water, power and sewage into the site, the city also has to be satisfied that garbage and fire trucks have unimpeded access. In addition, there are privacy issues with nearby neighbours, and requirements for parking spaces and outdoor space that have to be either met or argued to the point of gaining a variance. Both the Shaftesbury and Croft houses feature ingenious solutions to these issues, involving clever structural fixes and innovative features such as roof gardens and internal courtyards, which probably explains why laneway houses evoke such passionate advocacy from architects and the urban design aficionados who commission them.

City Hall is certainly unenthusiastic about the spread of laneway housing, insisting that it isn't necessary to the city's long-term growth plan, which concentrates on the condo-heavy downtown, the "avenues" (major streets) and discrete development zones such as Yonge and Eglinton, Etobicoke, Scarborough and North York.

"Laneway housing is not a key component in the City's plans for growth," says David Oikawa, Manager of Community Planning for Toronto and East York. "Laneway housing has potential adverse impacts such as over-intensification of lots, servicing issues, health and safety issues and overlook into adjacent properties. Laneway housing may be acceptable in a neighbourhood where there is a history of it in the neighbourhood and it forms part of the character of an area, but laneway housing needs to be examined on a case-by-case basis to determine if fits within a neighbourhood."

Proponents of laneway housing argue that, while many of the obstacles listed by the city are reasonable, it's an option that should be more often on the table, if only for reasons that transcend issues such as density. Architects Christine Ho Ping Kong and Peter Tan built their Carleton Village laneway house on an unusually large site near Davenport and Old Weston Road, retaining three cinder-block walls of a contractor's warehouse to create a live/work space with courtyard areas on two floors.

Tan says that it was his experience growing up in Thailand, in addition to a thesis he did of Kensington Market's laneways and the couple's travels in Europe and Asia that opened their eyes to the potential of laneway housing, which they say is usually championed by people who've traveled to places where urban real estate is both scarce and expensive, resulting in cities that have built into every corner and crevice.

"Having these layers and parallels are what makes cities amazing places to be," Tan says, "that you can discover corners that you never thought existed - it gives it layers that a city like Toronto desperately lacks. Cities like Rome that have all these layers and collisions of different things happening, you can really experience that, and if the laneways were developed that's what you'd get in the city - layers of experience."

For Elena Soni, who commissioned the Shaftesbury laneway house that recycled the rusted steel cladding of the workshop that stood on the site, location and uniqueness more than make up for the lack of space. "The city will have to change its mind because in order to keep neighbourhoods healthy you need to have people living in them, with eyes on the street all the time, and we have no more space in Toronto. So the more laneway housing we make the more alive our core will be. To anyone willing to undertake this I say keep it on, and the city will have to change its ways."

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments