What ever happened to velo-city?

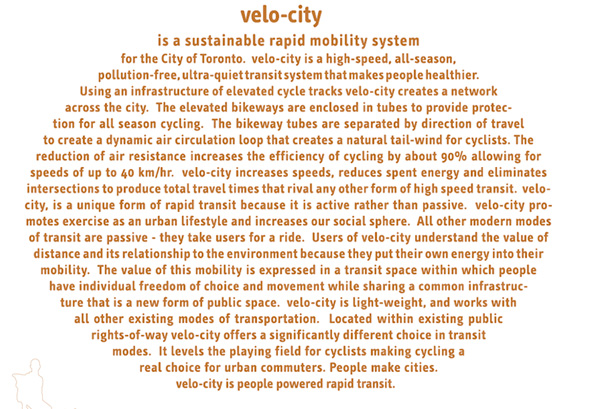

Anyone remember velo-city, the elevated bikeway network proposed by Toronto architect Chris Hardwicke back in 2006? The project got quite a bit of attention when it was first proposed, most likely because it was just so outlandish. While it made sense to think of ways to create cycling infrastructure that was independent of existing roadways and solved the problem of our unfriendly winter weather, the question was where would the money come from to build such a project?

Well, as it happens, nowhere. Not surprisingly, Hardwicke's idea never got off the ground (sorry, I couldn't resist) in any pragmatic sense. But does that mean it was foolish and naive? Some would say so, but I'm not so sure.

Doing research for another post last night, I happened to run into to some archived information about the velo-city project, which got me thinking about it again. Wouldn't it be great, I thought, to somehow send this idea back into the spotlight on the heels of Toronto's election of a less than cycling-friendly mayor? Isn't this just a more effective (albeit expensive) alternative to Rob Ford's idea to build bike lanes in ravines, where they won't interfere with vehicular traffic?

Now, I know that the realistic answer to the first of these questions is probably "no," but to indulge in a little lighthearted nostalgia, perhaps the very memory of the fact that a plan like Hardwicke's even existed -- unrealistic as it may be from a funding standpoint -- can sustain cycling infrastructure advocates as they battle for even the most modest of projects in the years to come. Think of it as the Elysian fields on the other side of the river Styx.

In fact, what's somewhat humorous is that if velo-city somehow did manage to get built when it was first proposed, it's not necessarily the type of project that Ford would hate. While the maintenance of the structures might be deemed an unnecessary expense, the key to Hardwicke's velo-city plans was the idea that the elevated cycling network would be placed alongside or on top of existing hydro, highway or railway corridors, which would thus diminish the degree to which the covered tubes would interfere with existing infrastructure and eliminate to add bike lanes to surface routes.

The reality is, of course, that given the current political and financial climate, it'd be bit silly to resume talking about velo-city in any serious way. Acquiring funding for such a project is an even more remote possibility today than it was four or five years ago. Yet, when I stumbled upon the project once again, I couldn't help writing about it. And, to be honest, it's not as if the idea of having specialized roadways for cyclists hasn't finally made its way to North America. In fact, if anything, it's gaining steam.

So for all the jokes, velo-city still stands as an example of a revolutionary way of thinking about cycling infrastructure and culture -- and that's worth remembering, at the very least.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments