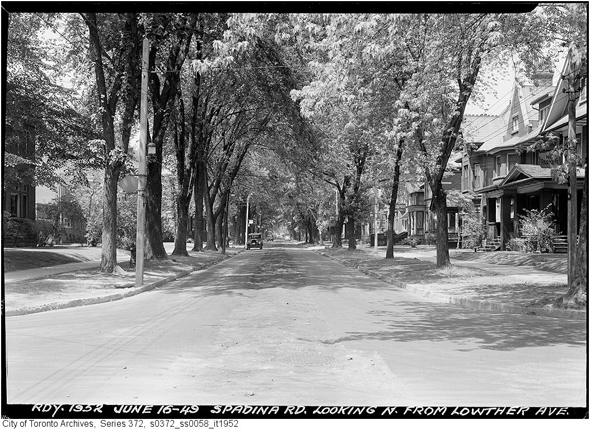

This is what the Annex was like in Toronto during the 1950s and 60s

The Annex remains one of my best-loved Toronto neighbourhoods.

Not only do I admire the architectural character of the residential streets, but I'm constantly drawn to the stretch of Bloor between Bathurst and Spadina on account of the fact that it houses a couple of my go-to used bookstores (BMV and Seekers Books) not to mention my favourite cinema, Hot Docs.

Like other inner-city neighbourhoods, the Annex experienced decline after WWII. Jack Batten, in The Annex: The Story of a Toronto Neighbourhood, writes that the middle- and upper-middle class residents gradually began to move to more exclusive neighbourhoods, including Rosedale and Forest Hill.

Why the exodus? According to Batten, two factors contributed to this shift away from the area: fear and snobbery.

Many widows, who, following deaths of their husbands, were no longer able to afford their residences, began to rent rooms, eventually turning their homes into boarding houses.

Over time, this practice became more widespread and the older residents started to see this as the beginning of a social upheaval.

Other older suburbs, such as the ones mentioned above, offered them more land on which bigger houses could be built, whereas in the Annex, lots are close to each other, offering limited opportunities for structural expansion.

The move of numerous fraternities to the residential core of the neighbourhood north of Bloor was also seen as a deteriorating factor.

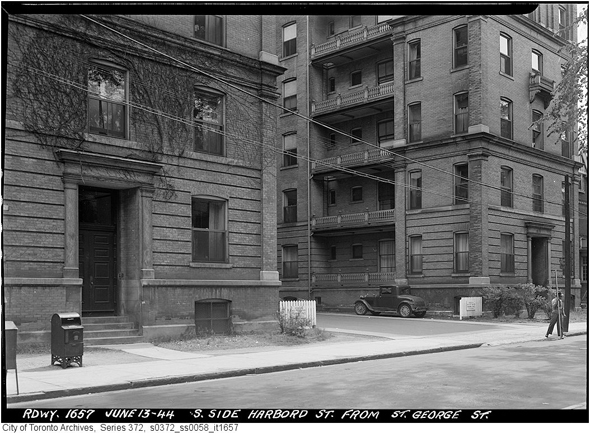

University of Toronto expropriated some fraternal residences on St. George Street in order to construct Innis College and other academic buildings.

The fraternities posed a problem particularly to the residents of Madison Avenue, Lowther Avenue and the north section of St. George.

Trade in illegal drugs began in the 1960s in the Annex, and the residents of Howland Avenue jokingly referred to their street as "speed alley" at that time.

In the same decade, many of the residential houses became homes to small commercial enterprises, such as minor magazines and charities.

Admiral Road and St. George St. in 1957.

Fortunately, the decline of the Annex was short-lived. Starting in the late 1960s, when U of T professors and middle-class families began to buy and renovates the houses, that value of which had dropped following the war.

The older, established homeowners, who remained in the Annex, kept their houses in a good condition in spite of the gradual deterioration of the area, and the ratepayers association reorganized itself to lobby against developers.

The corner of St. George and Lowther in 1967.

Inevitably, however, the character of the neighbourhood started to change again. The north section of St. George Street and its vicinity are characterized by an interesting mix of E.J. Lennox's handsome Richardsonian Romanesque houses and Uno Prii's apartment buildings.

The stark differences between the two symbolize the change in the Annex as a neighbourhood of single-family residences and rooming houses to an area of a much higher density stemming from the postwar population boom.

Prii rejected the influential and fashionable Bauhaus and Stark Modernism, whose styles were characterized by straight lines and cubist shapes.

In his own designs, he emphasized circles, loops, and curves. In 1957, he established his own architectural firm and soon his clients included apartment developers.

One of Prii's designs located in the Annex is the Prince Arthur Towers at 20 Prince Arthur Avenue, erected in 1968. It is twenty-two storeys and described as "massive, monumental, and shocking."

Here, Prii attempted to combine old and new, medieval and modern. The most striking are the sixteen flying buttresses, half of them in the front and the other half in the back, curving from the roof to the base.

The first few decades following the war contributed greatly not just to the architectural character of the neighbourhood today, but also its commercial and residential mix.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments