The story of the first Yonge Street pedestrian mall

As we wrote about yesterday, there's talk of bringing a pedestrian mall back to Yonge Street. If such a plan materializes, it'd mark the second time that the street has been used in such a capacity. So what happened with the first experiment? Originally submitted as a geography assignment at U of T, Astrid Idlewild and Duncan Taylor tell the story of the time "When Queen's Park smothered Toronto's Yonge."

WHAT WAS IT, AND WAS IT YEAR-ROUND?

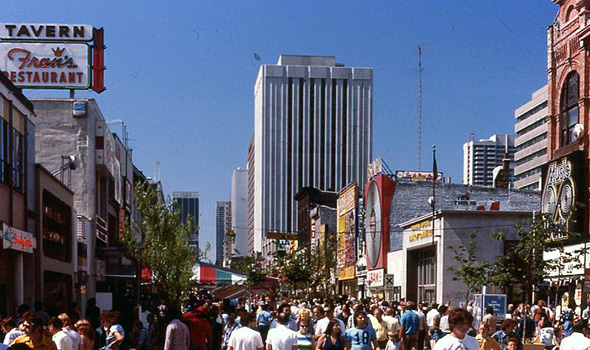

In summer 1971, the City of Toronto conducted a public spacing experiment: close Yonge Street to vehicle traffic and open it to pedestrian access, open-air cafĂŠs, street musician performances, and independent vendors. Under Mayor David Crombie's municipal government, City Council expressed concern with the lack of "open spaces" inside the "Core," or central business district.

Unlike other North American cities contemplating street malls, Yonge Street Mall wasn't intended as an economic stimulus (Yonge was doing quite well already). Rather, given high pedestrian activity in a just completed Commerce Court Square (at King and Bay Streets), the City identified a need to increase the ratio of open public space in the Core; the most affordable way to do this was to open a street Mall.

The Mall was a summer-only space: it premiered for two weeks in 1971; expanded to eleven weeks in 1972 & 1973; and eight weeks in 1974.

WHERE ON YONGE WAS THIS?

It varied slightly each year, but it was generally the 1.3-kilometre stretch between Wellington St. (on the south) and Gerrard St. (on the north). Each major intersection enabled east-west vehicle traffic to cross.

HAD OTHER STREETS BEEN CONSIDERED?

Bay St., Yorkville Ave., and Elizabeth St. were evaluated, but Yonge Street won out in 1970. It was chosen due to its ready TTC subway accessibility and its familiarity to both residents and tourists.

WAS IT BAD FOR BUSINESS?

Acclaim for the Mall in 1971 was emphatic. The Mall Project found in their year-by-year surveys that 78 percent of proprietors along the corridor rated it "good for business." 93 percent supported keeping the Mall running from two weeks to year-round -- broken down, approval was 88 percent of retailers; and 100 percent of eateries, financial services, entertainment, and personal service businesses.

But time tempered that cheerful timbre. By 1973, increased pedestrian activity drew greater awareness to criminalized activity -- namely, public intoxication, panhandling, prostitution, gay bashing, and leafletting for sex-related activity. Crombie's office recognized the need to manage municipal ownership to discourage these activities along the mall and prepared a request to the province to allow for that leverage. By 1974, merchant approval had dropped by half.

IF SO SUCCESSFUL, THEN WHY DID THEY STOP IT?

Yonge Street was a road contained within an incorporated Toronto. For the Mall to become a permanent fixture, the Mayor's office first required approval from three tiers of government: City Council, Metropolitan Council, and the provincial legislature at Queen's Park. In 1974, both councils approved the Mall's permanent installation. Crombie then approached the province to request two minor, but pivotal exemptions from the province's Municipal Act: one, to protect the City from being sued by shopkeepers for liability damages related to the Mall; and two, to give the City authority to limit leafletting on the Mall without a municipally-issued permit.

As holder of that city corporation and favouring the interests of well-moneyed objectors (such as the Simpsons' and Eaton's families), Queen's Park declined to grant Crombie these exemptions from the Municipal Act. Without provincial support, the Mall was relegated to dissolution after 1974. Despite its shortcomings, the Mall enjoyed continued public support. Queen's Park, by asserting its constitutional control over Toronto, enforced how municipalities were beholden to the province, making them unable to assert leverage without first seeking approval. It vetted the notion that cities, even Canada's

largest, were still "creatures of the province".

WHERE DID THE STREET ACTIVITY GO?

Once the Mall closed, foot activity shifted slowly to the PATH underground tunnels (devised by property owners to create real estate in unused basements) and the Eaton Centre.

WHY DOES IT MATTER NOW?

The Mall offers a comparative lesson to contrast against a modern-day, public-private partnership like Yonge-Dundas Square. At first, it seems unusual that the City scrapped the Mall idea entirely. Acquiring private space is a costly, protracted process involving approvals by multiple parties, expropriations, and pending real estate deals. Securing approval for razing buildings to construct a Square needed several years and political dealings; by comparison, the Mall was prepared in a short period of time.

But as Queen's Park's decision demonstrated, a public-driven, publicly-spaced initiative -- even when it smartly demonstrated a potent economic, social, and cultural engine for Toronto -- was off the table if they so chose, forcing the city to explore other measures that would not require provincial approval.

Writing by Astrid Idlewild and Duncan Taylor.

Photos (in order) from the Toronto Archives and Wikimedia Commons.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments