The history of the Toronto Lunatic Asylum

Riding the streetcar on Queen Street West near Ossington Avenue, it's impossible not to notice the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

Over the years, the site has witnessed evolving modes of psychiatric treatment, some of which eventually came to be questionable, dating back to 1850.

According to the Toronto Public Library, the Provincial Lunatic Asylum (as it was then known) at 999 Queen West was the first institution in the province to care for the mentally ill.

The establishment of such an institution was part of the larger shift in Europe and North America toward the confinement of the "insane", as their care was increasingly perceived to be the responsibility of the state.

Prior to this, the care of the mentally ill (often referred to in such derogatory terms as "lunatics" and "maniacs"), were in care of their family or were placed in jails and poor houses.

The term "asylum" is now associated in popular culture with Victorian Gothic Revival architecture and imaginary ghostly appearances, but at the time, these institutions were founded as benevolent places of refuge.

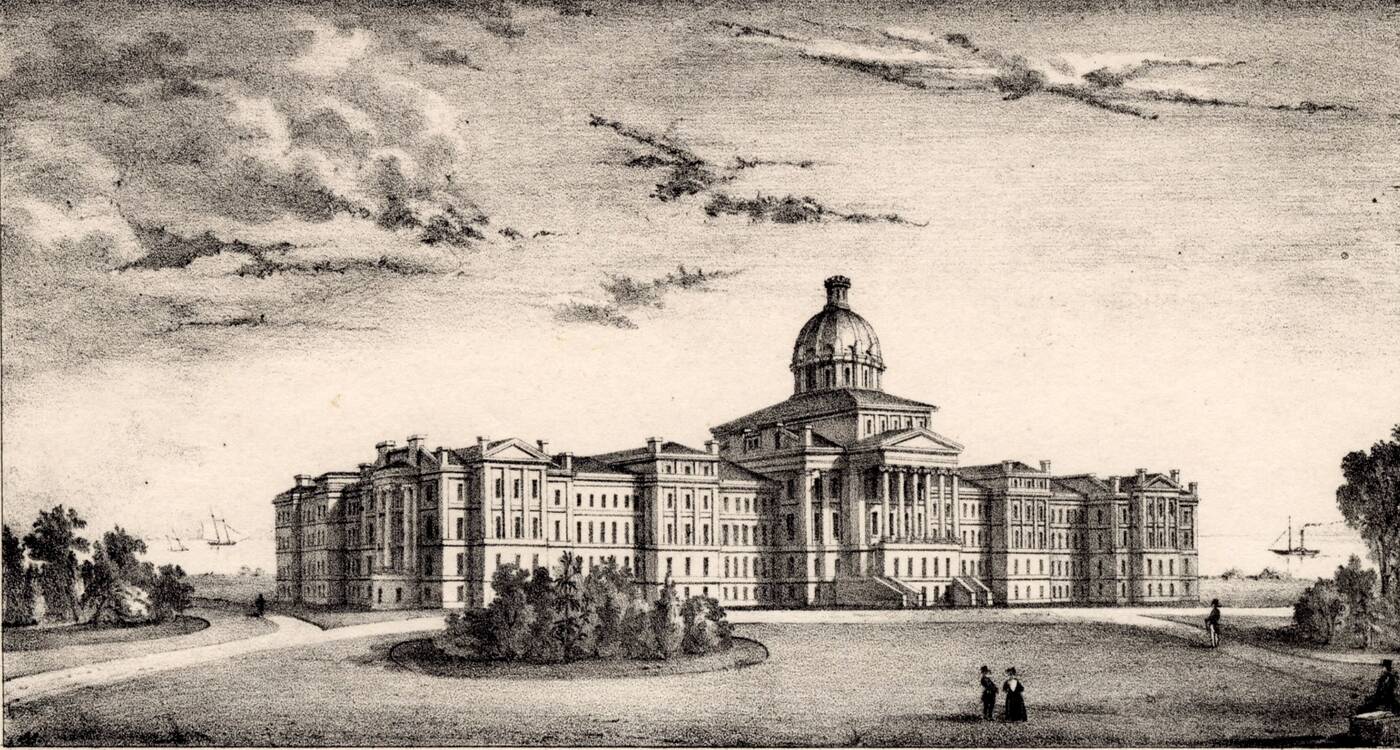

The Toronto Lunatic Asylum, 1868. Photo from Toronto Library Archives.

Over time, however, many of these institutions succumbed to chronic overcrowding and shortage of staff. Subsequently, they became something akin to warehouses for the containment of the insane, where violence was an everyday reality and medical care was scarce.

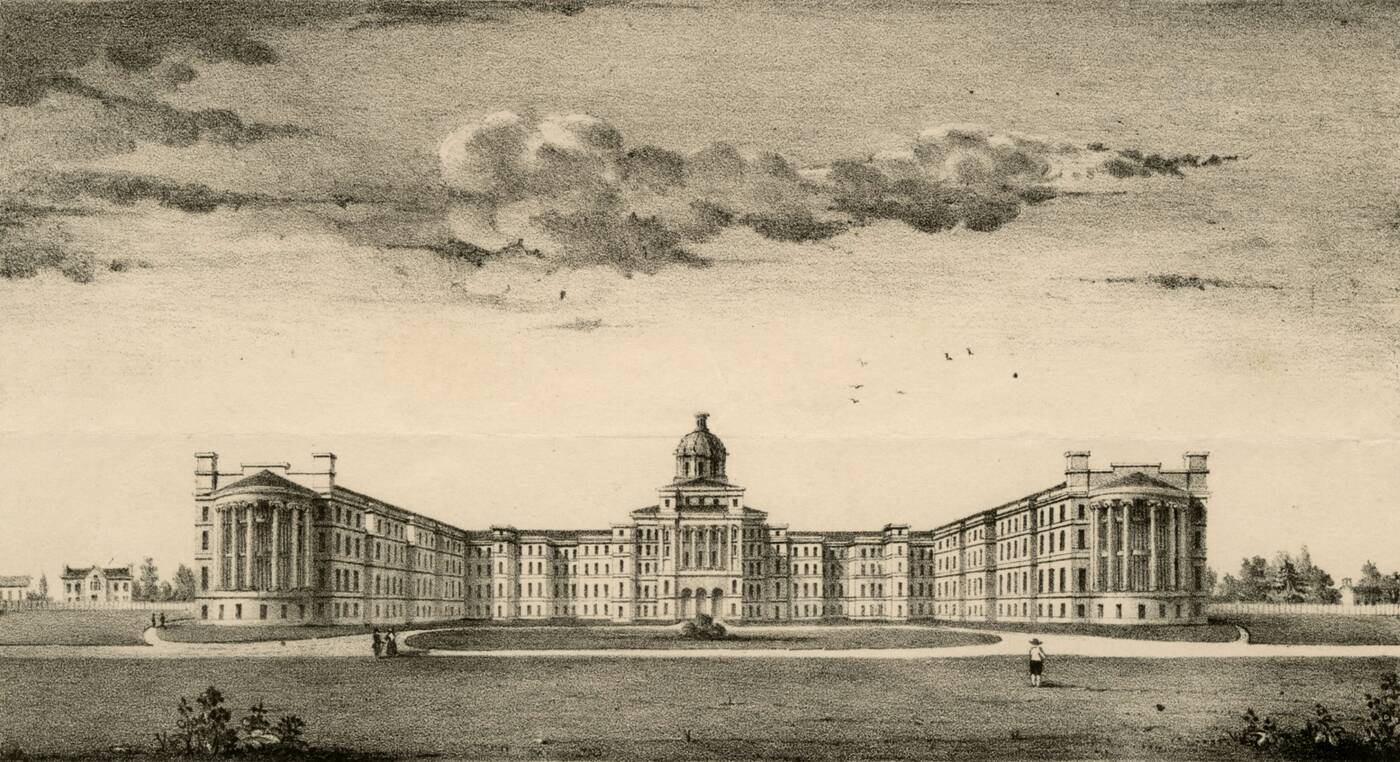

The structure, encompassed on all sides by sprawling 50-acre property, which was part of the Garrison Reserve, was designed by architect John George Howard.

Construction began in 1846 and the asylum officially received its first patients on January 26, 1850.

The building was considered a modern facility, equipped with central heating, mechanical ventilation, and indoor plumbing. The main cupola over the front entrance contained a water tank. The landscape was also carefully laid out.

The Lunatic Asylum in 1849. Image from Toronto Public Library.

Kivas Tully, who was later appointed as the chief provincial architect, designed the wings that were added between 1866 and 1870.

It was located near the city limits, and the inmates were required to work on the asylum farm without any compensation. It was considered beneficial for them to engage in light labour, even though the farmwork was quite the opposite.

At the same time, these conveniences represented a more humane approach to the confinement and treatment of the insane.

This new attitude, known as "moral management," was directly influenced by such intellectuals as Thomas Kirkbride and Philippe Pinel, who emphasized kindness, light restrains, cheerful surroundings, and relaxing domestic tasks as part of therapy.

The first superintendent, Dr. Joseph Workman, directly espoused these principles in his work and treatment.

The Toronto Lunatic Asylum, 1849. Image from Toronto Public Library.

In spite of these advances, the asylum experienced overcrowding from the beginning, with further decline of quality of treatment that occurred following World War I.

It was eventually renamed as the Toronto Lunatic Asylum. In the 1950s, the hospital introduced numerous outpatient programs and was renamed Queen Street Mental Health Centre.

The old structure started to be demolished in 1975, in spite of opposition from heritage advocates, who aimed to bring attention to its architectural merit.

The original wall of the asylum, built by inmates, is all that's been preserved, mainly due to the efforts of the Psychiatric Survivor Archives of Toronto.

The process of deinstitutionlization, which began following World War II, favoured community-based psychiatric programs over long-term confinement of the mentally ill.

In addition, large-scale Victorian asylums, which began as places of refuge, were now perceived as antiquated facilities, not suited for more modern, advanced psychiatric care.

First psychiatric drugs were introduced in the 1950s, which resulted in lower patient populations. At the same time, only a small percentage of the new programs materialized, and were therefore inadequate. As a result, many of the former inpatients became homeless.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments