Five ill-fated projects from Unbuilt Toronto 2

On Wednesday night Mark Osbaldeston gave a talk at the ROM about his second book, Unbuilt Toronto 2. It was great opportunity for fans of the author's lost histories of the city to hear him offer additional insights and a few opinions about the Toronto that might have been. A confident and engaging speaker, Osbaldeston highlighted some of the most interesting unbuilt projects from his latest prolonged dive into the archives. Here are five worthing knowing about.

1. The ROM was built on napkins

In 2001, when Daniel Libeskind submitted his proposal for the addition of his much-maligned crystal to the north facade of the ROM, he did so on napkins from the museum's restaurant. In doing so, he probably wasn't aware that almost 100 years prior, the original plans for the ROM were similarly sketched on a envelope.

In 1903, Charles Currelly, a man who would become one of the ROM's early directors, met Sir Aston Webb, the architect who famously designed the front facade of Buckingham Palace. Riding on a train to London, Currelly asked him what he thought was the best design for a modern museum. Webb obliged him by saying that he had contemplated the matter extensively and then drew him his ideal design on the aforementioned envelope. After arriving in London, Currelly sent the envelope back to Canada to the building's architects.

It turns out the design that Webb had suggested was popular during its time and the ROM's original architects, a firm by the name of Pearson and Darling, were going to use something similar anyway. Although the beautiful design was never fully realized due to the outbreak of World War I, the building's west side gives a glimpse of what might have been.

2. Dundas West could have been a contender

In 1963, planners from the Art Gallery of Ontario proposed a promenade that would have drastically altered the look and feel of Dundas Street. They envisioned a grand pedestrian promenade that would start at University and lead west on toward McCaul. The planners of the walkway even managed to buy three of the four blocks required for the project, but they lacked the necessary funds to seal the deal (not surprisingly, they weren't offered any provincial funds for the project). After appealing to several different sources for capital without success, the plan was abandoned.

While the dream of the promenade never came to existence, the surrounding area still hints at the ambitious plan, though in a much reduced fashion. The 52nd Police Division is equally set back with the AGO in preparation for the walkway, and the OCAD building closest to the AGO received a rather meagre — some might say pathetic — colonnade, which students now use to lock up their bikes.

3. Doug Ford belongs in the 1970s

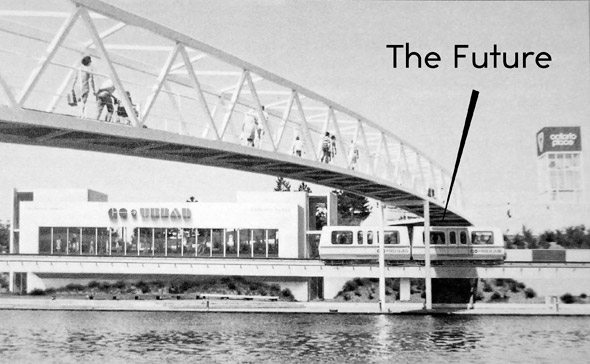

In 1971, after cancelling the Spadina Expressway, the provincial government started to look for new ways by which to expedite the transportation of a burgeoning number of Southern Ontarians. The plan they eventually settled on? Monorails — or at least something very close. This particular technology was referred to as intermediate capacity transit systems (ICTS).

By 1973, the government had decided to build a 5.6 kilometre proof-of-concept track that would encircle the CNE grounds. They hoped the new system be in place for the 1975 CNE Fair. The government asked three companies to draft proposals for the vehicles that would service the track. KraussMaffei, a now-defunct transportation firm from Munich, dazzled the province's bureaucrats with their vision of the future: driverless, computer-controlled cars that would glide through the air courtesy of magnets above elevated rails.

The project quite literally became derailed when it was discovered that the vehicle which KraussMaffei designed had a tendency to blow a magnet when it took to a curve on the track. KraussMaffei quickly lost the support of both the provincial government and the West German government, which had subsidized much of its work. And on November 13, 1974, the undertaking was cancelled. Over the next year, the guideways that had been built to support the trains were removed, and with them, the dream of a driverless transit in the GTA.

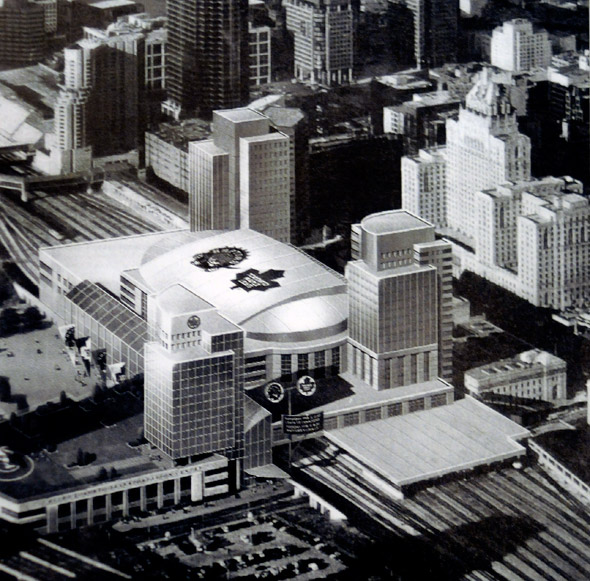

4. How about an arena on top of Union Station?

By the start of the 1990s, the Leafs decided that they desperately needed a new venue. Maple Leaf Gardens was just too small and too lacking in concession stands to allow the company to maximize profits. Around the same time, the Toronto Raptors had became one of the NBA's newest franchises. Although it always made sense that both teams would play out of the same venue, in 1996 the Raptors had purchased land that the Air Canada Centre would eventually occupy. The Raptors approached the Leafs about sharing the future building, but the latter decided that the site of the proposed stadium wasn't prestigious enough given their storied history.

The Leafs, however, still wanted to hookup with the Raptors, and decided that a 19,000 seat venue behind and above Union Station was what would entice the basketball team. Unfortunately for the Leafs, the complications related to the land proved too difficult to overcome, and the site was ditched. Undaunted, the team then proposed to build a new arena at the Exhibition grounds. The team seemed ready to commit to the site, but on February 12, 1998 it made a surprise announcement that it was buying the Raptors and their venue — yeah, the same one that was once beneath them.

5. On Toronto's putative impotence

Asked by an audience member why Toronto has often failed to pull the trigger on ambitious building projects, Osbaldeston answered that, in his opinion, a culture of parsimony and parochialism has been pervasive in the city. The example that he provided — though he probably could have used many others as well — was that when it came time to secure the funding for a proposed 1910 subway system in Toronto, it wasn't the provincial or federal governments lack of support that doomed the project, but the city's electorate, who, when asked in a 1916 municipal ballot, refused to endorse the undertaking.

Osbaldeston later qualified his answer somewhat, saying that he's encouraged by the increasing level of sophisticated discourse that the public engages in regarding the city's building plans, though I doubt that's much of a consolidation to those for whom Transit City likely represented the panacea to their early morning commuting woes.

Photo credits from Unbuilt Toronto source material, Sam Javanrouh, and Torontovore.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments