That time when the Toronto Star was the Daily Planet

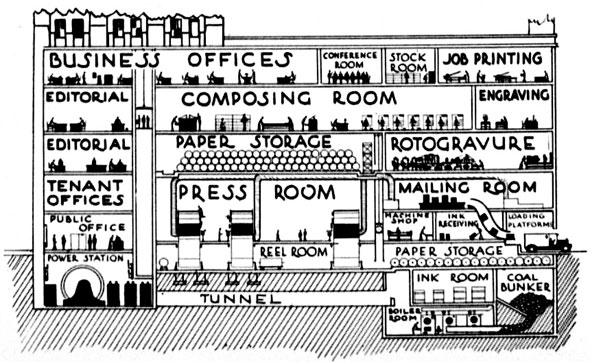

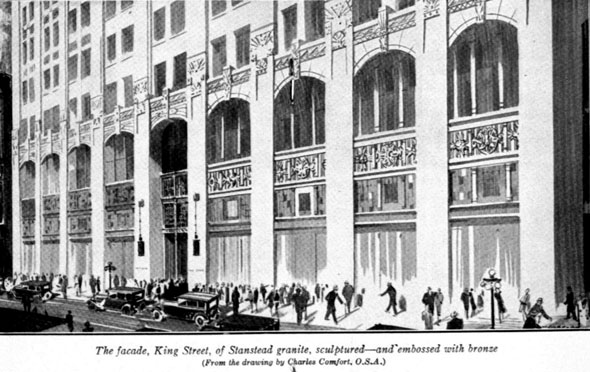

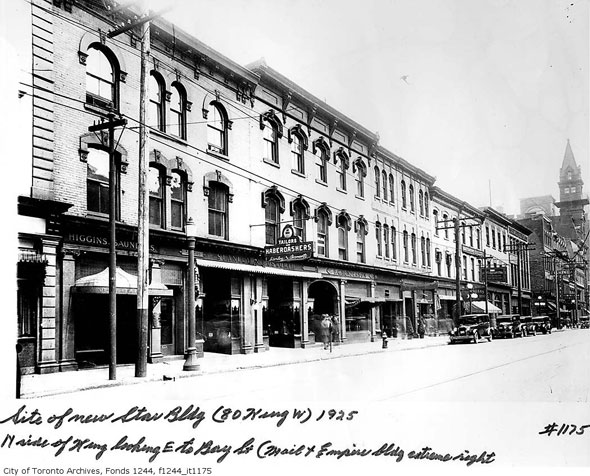

Before it moved to 1 Yonge Street, an absolute monstrosity on the waterfront, the Toronto Star was headquartered in a stunning, 22-storey art deco tower at King and Bay. When it was opened in 1922, the Toronto Star Building was equipped with a state-of-the-art newsroom, printing press, and even its own power station.

The building had two plumbing systems: one for water, one for ink. The floors were connected by a conventional elevator and a set of fireman's poles that, among other things, allowed journalists to swoop between the newsroom and reel room in a flash, presumably to yell "stop the press!" or whatever the journalists of old used to do. It even inspired a key part of the world's most famous superhero.

A commemorative booklet handed out when the granite and limestone tower was officially unveiled to the public describes the building as a "symphony of vertical lines" that "recede and fade into the sky ... like a mountain top." It's safe to say the newspaper took their new home very seriously.

And rightly so. The Star Building was a treasure trove of innovation we can only marvel at today. Thirty miles of pipes lined its walls, a special "one-man air lift," which sadly seems to be lost, "[shot] a man up to the press room almost as quickly as he [could] slide down (the fire pole)." Special "washed air" humidity controls forced treated air around the building."

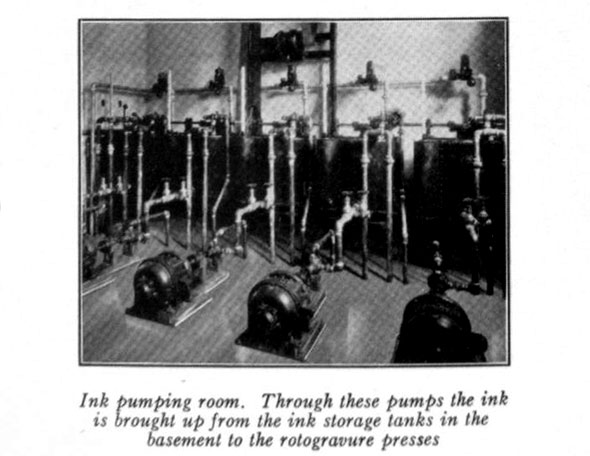

Starting in the basement, the Star Building had its own hydro-electric substation to feed power to the giant printing press located several floors above in the rear of the building. A tunnel led under the reel room to a coal bunker off Pearl Street. Here, a team of workers fed the building's heating system like a scene out of the movie Titanic. The ink storage room, the hub of the tower's ink plumbing system, sat just above.

The beating heart of the Star was located in the central core of the lower floors. Here, receivers feverishly typed up incoming rushes in the wire room, printer machines ("a combination of typewriter and telegraph") automatically tapped out dispatches from across the continent, and writers, editors, and copy-handlers processed and flushed the finished stories down special tubes to the printing room.

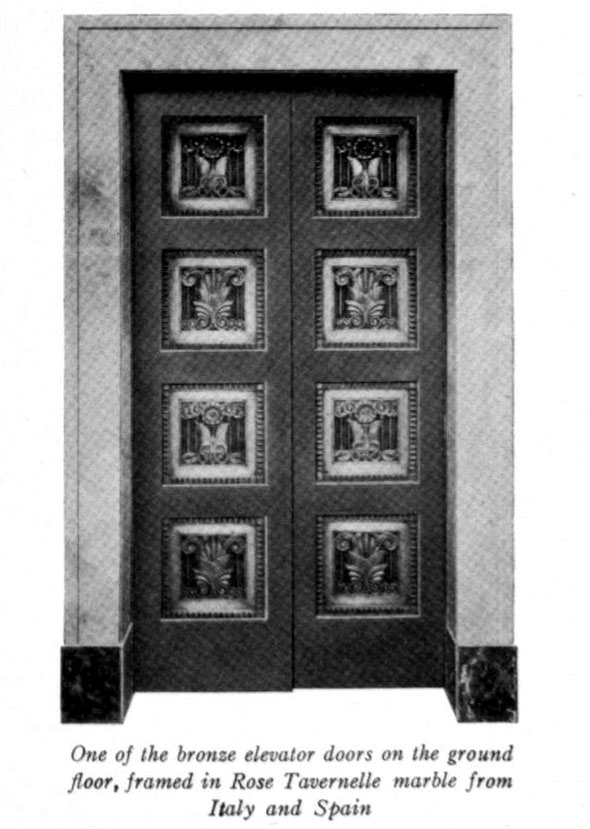

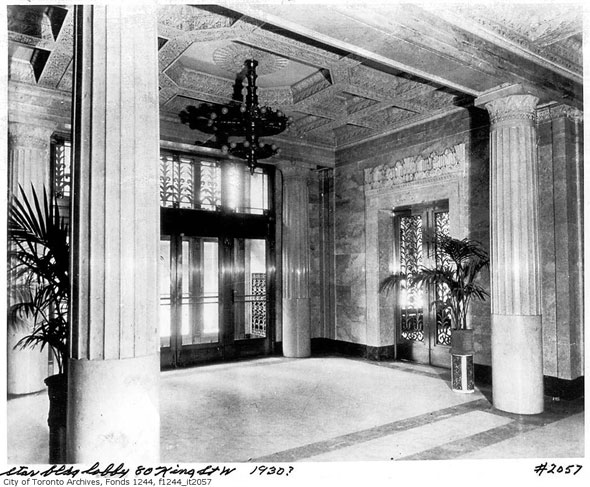

The souvenir pamphlet was also keen to sing the praises of the Star's bank of electric elevators. Set behind bronze doors, the operator-controlled lifts were among the first in Canada to use entirely electric signals to select the destination floor. It's not exactly clear why operators were needed at all â the system seems to be practically identical to what we expect to find in an elevator today â but this was the glory days of newspapers and there was plenty of money to spare.

The author even wonders if elevators controlled by mental telepathy are on the horizon.

Superman co-creator Joe Shuster clearly saw the magic of the Star Building. He based the look of Clark Kent's Daily Planet building on 80 King Street West. As a youngster, Shuster worked as a paperboy for the company, delivering the Toronto Daily Star door-to-door.

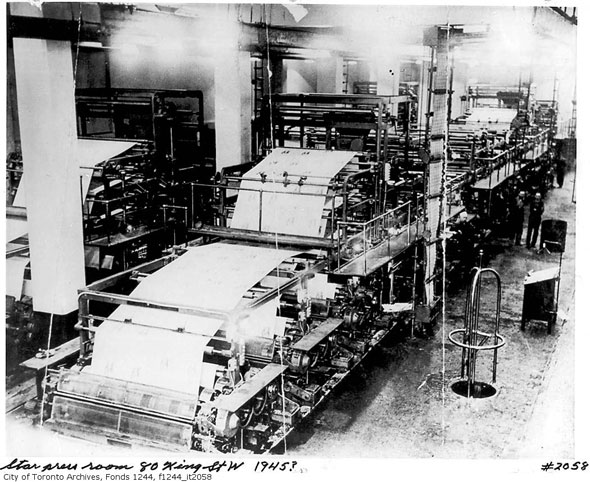

The journalists huddled around their desks in the picture above are working on the Thursday 18th September 1930 edition of the paper. Thanks to the Toronto Public Library, you can view the finished product here. The big news of the day was the struggles of Sir Thomas Lipton's yacht, the "Shamrock V," in the America's Cup. Lipton founded the Lipton tea company and regular entered boats in the sailing competition.

The Shamrock V would be plagued by bad luck during Lipton's fifth and final attempt at the prize, and would ultimately lose out to the yacht Enterprise, captained by the ruthless Harold Vanderbilt. Lipton died a year later, never fulfilling his dream of winning the competition.

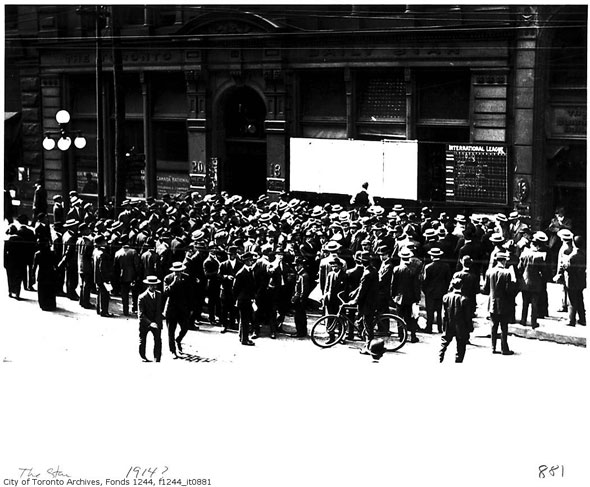

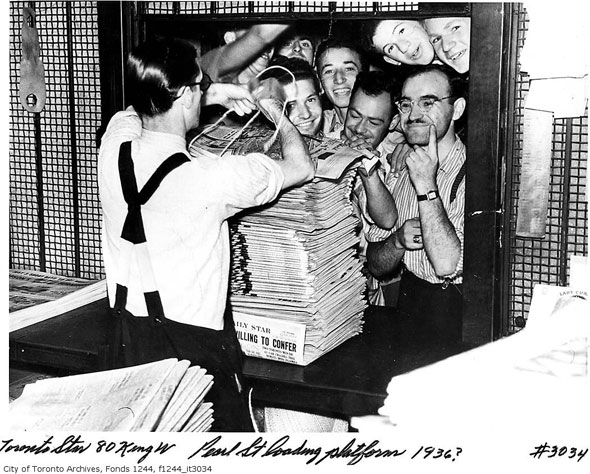

In the days before television and radio became established sources for breaking news, the Star regularly used the street outside its headquarters to deliver public bulletins. During major stories, people crowded the street, which was also home to the Globe and Mail (the pointed tower in the background of the second image) to snatch a copy of the latest edition of the paper. The Star also regularly set up baseball and hockey scoreboards outside the main entrance, as seen below.

The paper abandoned the building in 1970 for its new waterfront headquarters and the tower lay vacant for several years. It was eventually torn down in 1972 to make way for First Canadian Place.

Portions of the stonework can still be found on the grounds of Guild Inn in Scarborough, a portion of land home to several recovered pieces of lost Toronto buildings. Chapman and Oxley, the building's architects, would go on to design The Bay building at Queen and Yonge and the Toronto Reference Library, now the Koffler Student Centre.

MORE IMAGES:

News-hungry Torontonians clamor for a copy of The Star

A paper salesman sells The Star on the street

The ornate lobby of the Star Building

The ink pumps in the basement of the tower

A sketch of the granite and bronze facade

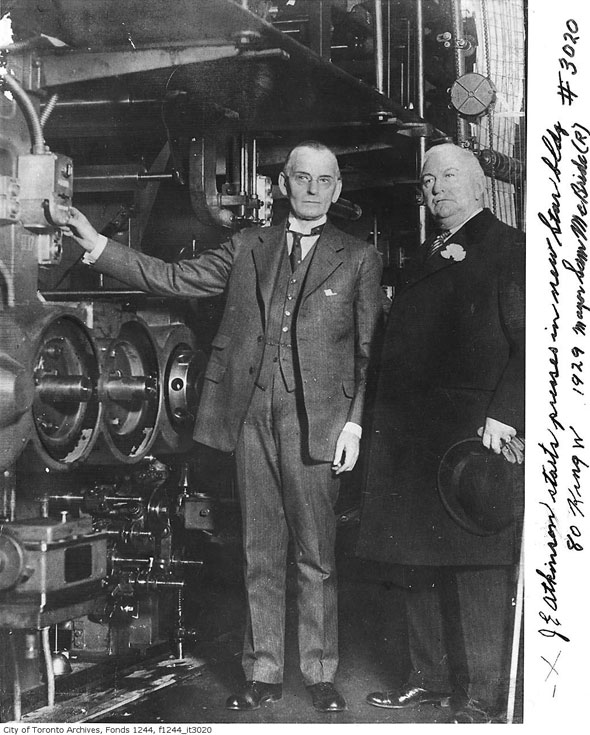

The new presses are started for the first time at 80 King West

Sports journalists at work

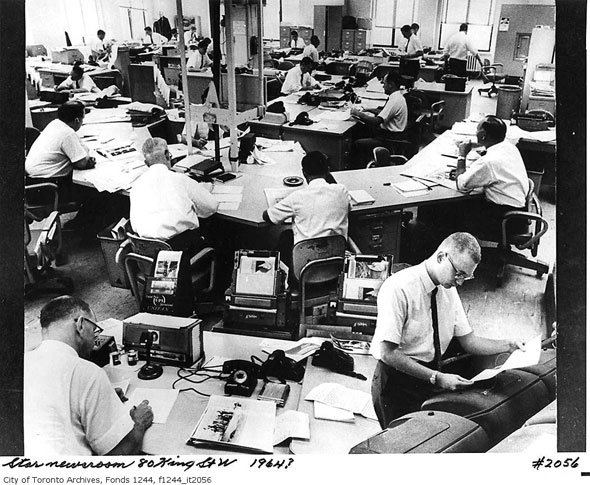

The newsroom as it appeared shortly before the paper moved out

The King West block before construction of the Star Building

Images: City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments