That time Toronto banks went to war over Scotia Plaza

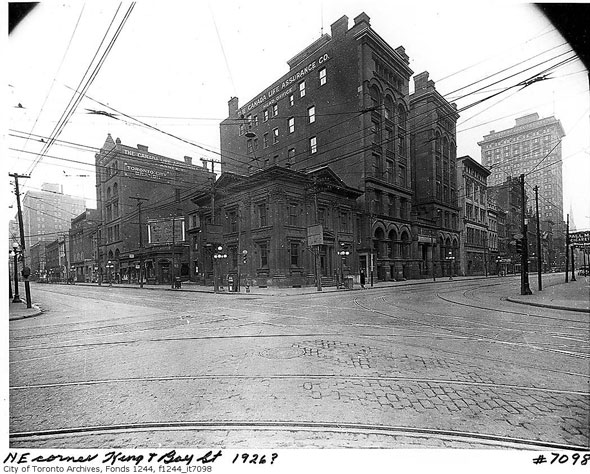

Before the TD Centre forever altered the appearance and scale of Toronto's skyline, the city was unaccustomed to battles over density and height restrictions. The financial centre was dominated by the Old Toronto Star Building, Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the Royal York Hotel, large stone structures all under 35 floors.

Those buildings were all finished within a year of 1930 and would hold dominion over the city's upper limits until Mies van der Rohe's obsidian towers, angular and modern, heralded a paradigm shift in Toronto's architecture and ignited the area's leasing market.

In the 1980s, the $430 million Scotia Plaza, a gigantic project that aimed to cash in on the flourishing rentals game, attracted a significant amount of press due to its developer's controversial deal to stretch the tower's size at the expense of existing density rules.

The agreement blurred the lines between deal-making and city planning and left a particularly sour taste in the mouth of TD bank, the building's would-be neighbours, who engaged a very public mudslinging match with the complex's developers, the Bank of Nova Scotia, and even Art Eggleton, the city's mayor.

Tower wars had arrived in Toronto.

Unveiled on Oct. 1982, Scotia Plaza was designed to be a giant from the outset. At 66 floors, the building would be second in size only to First Canadian Place, Canada's tallest office building that had been completed 7 years earlier.

The building's colossal size, a staggering twelve times over the zoning limit, was negotiated by the developer, Campeau Corp., who also owned vacant land at Yonge and Lake Shore. There, the company had planned to start construction on a mixed-use building several times higher than the city really wanted.

So, in a controversial move, Campeau was allowed to add 25 extra floors to the top of Scotia Plaza in exchange for reducing the size of its planned Lake Shore development. One of the first groups to publicly cry foul was rival banking group TD.

The first round in a bitter campaign against the project was fought before the city's land use committee. TD argued that Campeau and Bank of Nova Scotia (to use the bank's original name) gained more than $40 million in zoning concessions thanks to its deal with the city. J. Edgar Sexton, lawyer for the owners of TD Centre, likened the deal to a Houdini slieght of hand.

The committee wasn't much interested in TD's complaints. They voted 8-2 to reaffirm the city's support for the project, comparing the bank's rabid opposition to "corporate bullying."

At the time, the TD Centre was Toronto's most prestigious office address and the company was working on a new addition to the complex - the building now known as TD Waterhouse Tower - at the same time as the Scotia Plaza project.

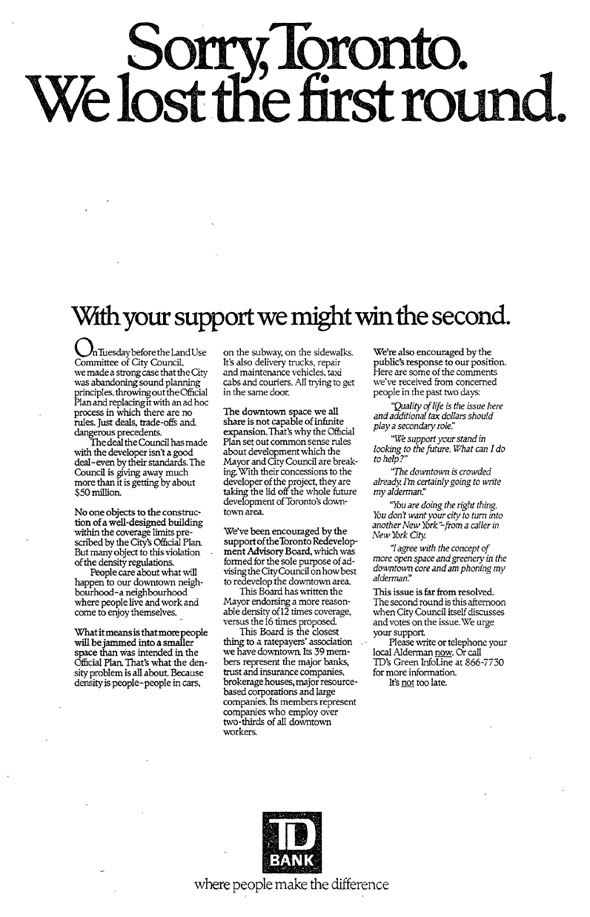

Shortly after its defeat at the land use committee, TD published an passive-aggressive attack ad in three of Toronto's daily papers, including the

Toronto Star. Though it avoided naming the project directly, the accompanying text accused the city of "abandoning sound planning principles" for "deals and trade-offs" in its approval of Scotia Plaza's density swap and signed off with a pledge to fight the final approval vote at city council.Meanwhile, confident of success, Ontario Premier William Davis, Toronto Mayor Art Eggleton, and Robert Campeau staged a "wrecking ceremony" using a scale model of the project site ahead of the crucial meeting. An editorial the same day worried about the city abandoning its own master plan in order to approve the tower.

Sensing the power of the political momentum building against it, TD attempted to stall progress with its last ace in the hole: the lease agreement to a building on Adelaide St. within the footprint of the proposed tower. In a play straight out of a spirited game of Monopoly, the bank asked a staggering $36 million in compensation, almost 10% of Campeau's estimate cost cost for the entire project.

Mayor Eggleton was so incensed by TD's politicking that he penned a scathing letter to Richard Thompson, head of Toronto-Dominion, accusing the bank of "misleading cheap shots," "media manipulating" and "fear-mongering." Toronto's leader stopped just short of signing his letter with a lengthy raspberry.

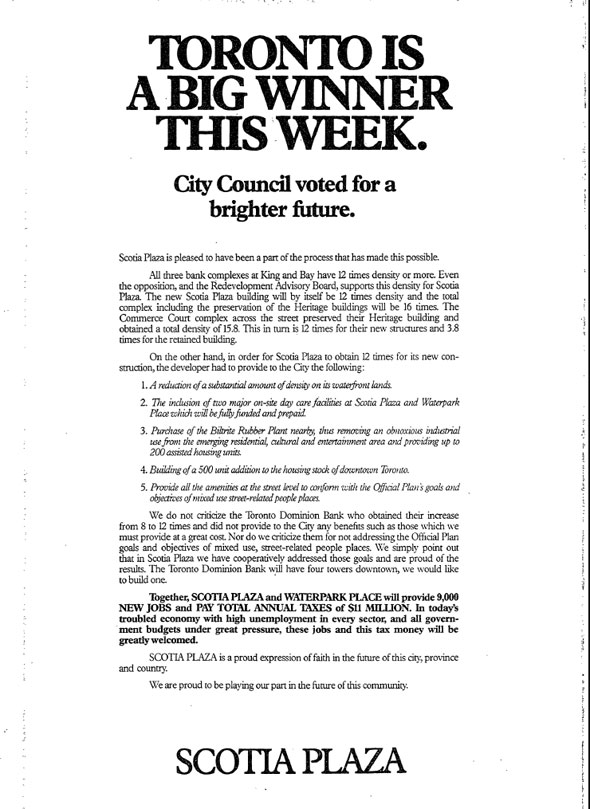

Two days later, after a marathon four-hour debate, city council approved the Scotia Plaza by a vote of 12-7 on the proviso Campeau build 200 units of assisted housing and keep the original Bank of Nova Scotia building. In true sporting manner, the ban and Campeau Corp. ran their own advert mocking the style and tone of the earlier TD missive, but the bank refused to lie down on the matter.

This wasn't the first time TD had made a fuss over rival banking groups for perceived encroachments on its turf. In 1972, while the paint was still wet on its own downtown offices, the bank fought against the bending of Piper St. northward for the construction of the Royal Bank Plaza because, they said, it would disrupt the entrance to their parking garage.

Despite suggesting it would appeal council's decision at the Ontario Municipal Board, the provincial watchdog with jurisdiction over Toronto's city council, TD quietly dropped its opposition in July 1984.

In the bank's place, Downtown Action, a long-dormant activist organization, took up the quarrel with Campeau. The group consisted of NDP councillors Jack Layton, later a vocal opponent of the SkyDome project, Dale Martin, and David Reville, as well as several others.

"While we don't have the massive economic and political clout of the Scotia Bank and Campeau Corp.," the group said in a press release. "We are inspired by the ancient story of David and Goliath and are hoping that this action will be the stone that brings the Scotia Plaza down to manageable proportions."

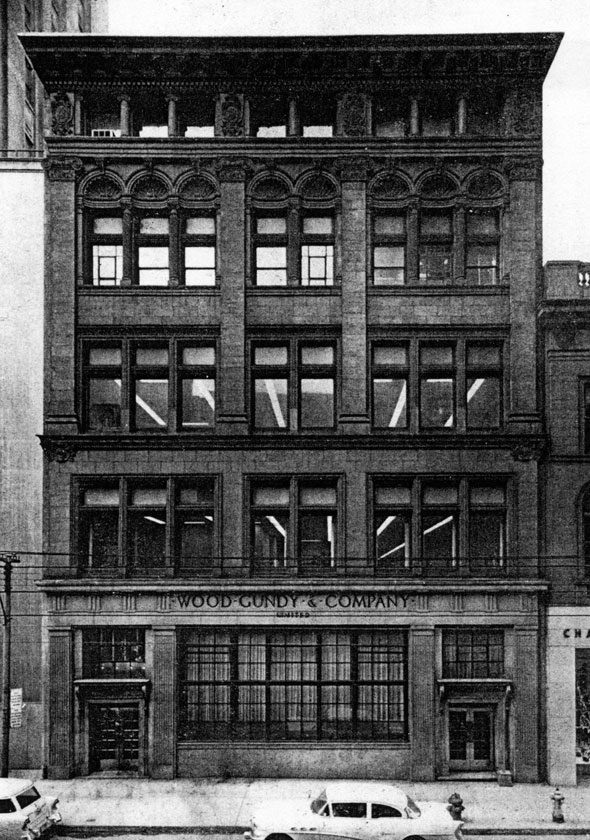

Meanwhile, Goliath was busy preparing the construction site. As part of its deal with the city, Campeau agreed to carefully dismantle the historic King St. facade of the Wood Gundy building and rebuild it immediately north on Adelaide. The 1,500-piece, terra-cotta and limestone structure was taken apart, cleaned with brushes, and put together a block north.

The 5-storey structure was originally home to Jon Kay and Son's carpet store; Wood Gundy, an underwriting and bonds specialist, now a CIBC company, carved its name above the door in the 1920s. Ironically, the brokerage firm moved to office space at TD Centre.

Then, with the hearing date looming, the non-profit Downtown Action abruptly withdrew its objections to the tower amid rumours of a clandestine $2 million deal with Campeau. The 5-member group had been active fighting housing issues in the late 1970s but had entered stasis prior to the Scotia Plaza saga.

It would later turn out Downtown Action had traded their silence for a $2 million donation to a housing co-operative from the developers. It was a good deal for Campeau - the legal costs and delays associated with an OMB hearing could have set the company back more than $10 million. Still, the closed-door deal left a bad taste in the mouth for those seeking transparency in the city building process.

A meeting by the city's land use committee would later find the NDP councillors "misused" the system, and all this before the building had even risen from its foundation pit. The

Star said the payoff cast a "long shadow" over due process in Toronto.TD's last desperate bid to stifle the tower's progress ended when the bank relinquished its lease to its hold-out branch. The fee was never disclosed, though it was definitely much less than the original asking fee. The building was hastily demolished with a wrecking ball though Campeau had asked to use an implosion device to save time (and look really cool.)

Despite being bogged down by delays, the Scotia Plaza project was perfectly timed to coincide with a leasing market boom in Toronto. As far back as 1986 experts were predicting its 1.5 million sq. ft. would in high demand as local companies grew and new ones arrived. One report predicted the market would grow by almost 50% by 1991.

It was good, then, that the building was beginning to take shape. The pit excavated for the building's foundation had already become the largest of its kind ever dug in Canada at 23 metres below street level. Then there was the Red Napoleon granite, shipped to North America from Italy and Sweden and stored in a staging area on Unwin Ave. in the Port Lands that would give the tower its unique colour.

At the heart of the work site, two West German-built cranes perched on the podium and rose with the tower, hoisting girders and assisting with concrete pours. The pair were named Falkor and Artax by school children in Europe after characters from The Never Ending Story and helped assemble the unique tubular construction that allowed for something approaching even weight distribution (some skyscrapers rely heavily on an inner core for support.)

The building's stats alone are impressive: 1,496 corner offices, 44 elevator cars, 28,000 exterior tiles, 5,000 windows, and 18,500 lights, all subtly brightened and dimmed automatically by a light sensing computer. A giant 2.95 million litre water tank in the basement circulates water through each floor, cooling in summer and heating in winter much like the Toronto's Enwave system does today.

Suddenly, with the building approaching full height, a faulty driveshaft in a construction elevator failed. The knock-on effect sent a car carrying two workers racing at more than 100 km/h toward the top of the shaft. Both were killed on impact and another man caught in the wreck was seriously injured. All work was suspended pending an investigation.

31-year-old crane operator Joe Dowdall, profiled in the Toronto Star two months earlier, underwent emergency spinal surgery. The fallout from the accident would rumble on for months as the families of the killed workers fought for compensation.

The building topped off on Feb. 10 1988 and opened later that year. The co-op housing units promised to the city were, at the time, held up in a building freeze on Queens Quay and tangled up in a land deals in the St. Lawrence neighbourhood. It did, however, go on to earn its owners the money they expected.

Scotia Plaza sold for $1.28 billion in 2012.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Public domain, City of Toronto Archives, "Wafers in Cherry Flavor" by yoyoeq/blogTO Flickr pool.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments