A brief history of Toronto's iconic Massey Hall

Massey Hall has been Toronto's premier music hall for more than a century. Its intimate confines and rich acoustics have made the Shuter St. building a mecca for music aficionados and a magnet for classic performances. This week, the venerable old institution turned 119 years old. It's also been 32 years since it was officially designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

Big changes are in store over the next few years: a deal with MOD Developments, the builders of the Massey Condos planned for 197 Yonge Street, has provided the cash for the biggest set of renovations in its history.

By 2020, the building will have traded in its famous fire escapes for a set of exterior walkways and a new back stage area. The red brick exterior, discolored by decades of pollution, will get a major buff and polish along with the famous neon sign. With big things ahead, it's time for a look back.

Hart Massey, born in Haldimand Township, Ontario, inherited his father's agriculture business aged 33 in 1856 and built it into a wildly successful equipment manufacturer.

At the time, many of the farms in Ontario were relying on basic tools. H. A. Massey and Company held the Ontario production rights for a mower, reaper, combined reaper, mower, self-raking reaper, and other important implements that would later prove invaluable and indispensable.

The business continued to grow with the creation of new foundries for forging parts and in 1867, the same year the company won an international award for its combined reaper and mower, Massey brought his son Charles on as partner.

Tragically for Hart, Charles died suddenly from typhoid on 12th February, 1884. The family decided the best way to commemorate their beloved son would be a $100,000 (almost $2,000,000 today) gift to Toronto, where the Masseys had many dealings. Charles was a skilled organist and pianist and it was felt his legacy should be musically inclined.

The Massey Music Hall was to be gifted in trust to the city for "musical entertainments of a moral and religious character, evangelical, educational, temperance, and benevolent work."

Interestingly, Massey also stated that the hall was "not to be a money-making property; the expenses are to be as low as possible, the revenue being merely intended to meet current expenses and to provide a sinking fund for repairs, insurance, etc."

"Everything beyond that is to go to reduce the price of admission, so that the hall may be to benefit the poor rather than the rich," the Globe reported. One idea revealed at the time was to sell tickets to a season of lectures for a nominal $1 fee.

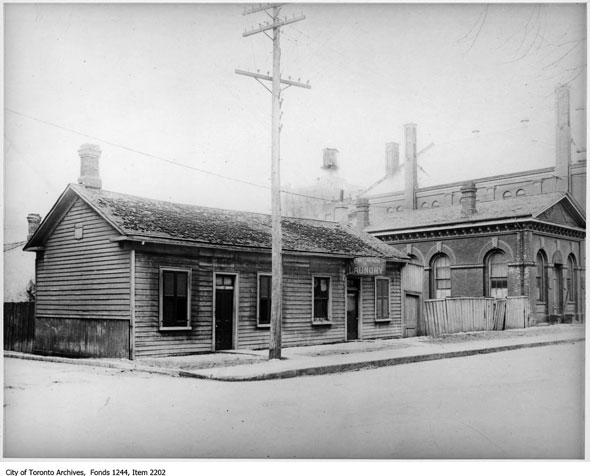

Over the next 10 years, Hart worked with his family and architect Sidney Rose Badgley to design the hall that would be built at Shuter and Victoria streets on the site of several wood frame houses.

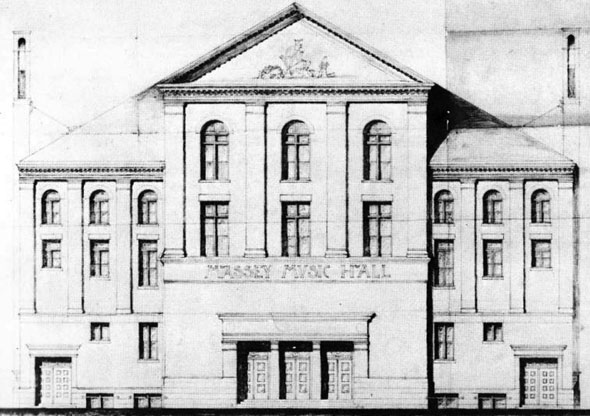

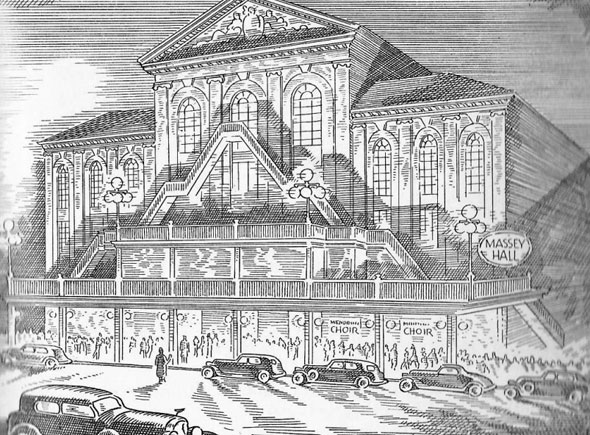

At the time, the city didn't have a secular space for choral and other musical performances. The design the Massey chose closely resembled that of the Cleveland Music Hall in Ohio. Hart Massey had a home there on Euclid Street, a stretch of sprawling mansions dubbed Millionaire's Row.

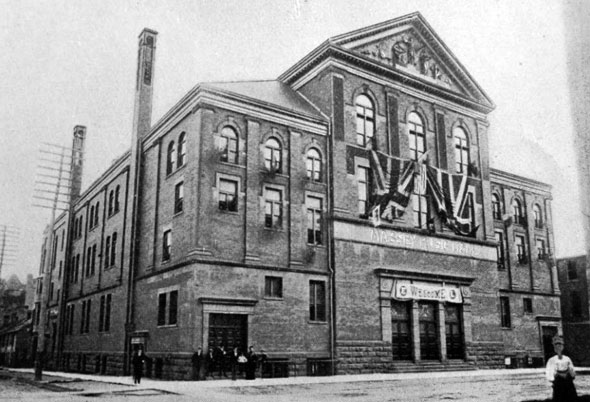

The three-storey, Don Valley pressed red brick building was built between 1893 and 1894 with on-site input from a second architect, George Martell Miller. The exterior of the building was kept relatively simple, possibly because of the family's Methodist faith, but many flourishes were included inside.

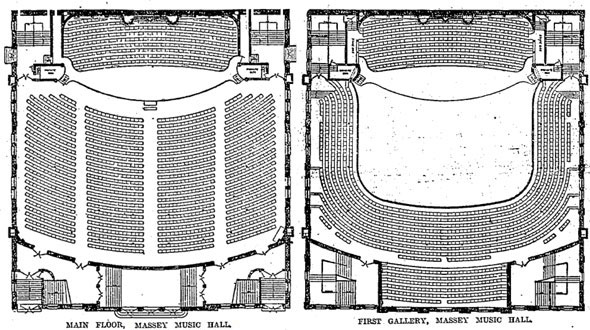

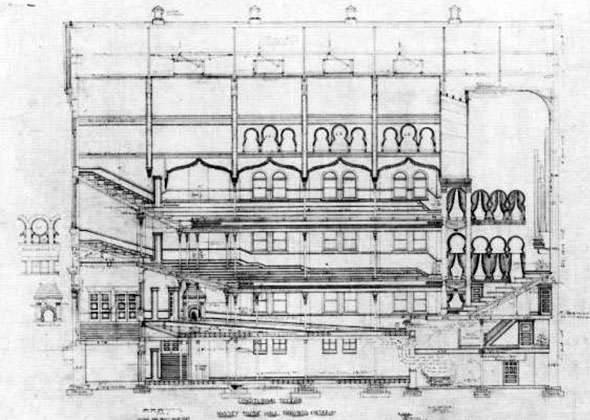

The gently arched roof was held aloft by four eight-ton iron trusses. There was officially room for 3,000 people though the Globe estimated 4,000 could squeeze in, perhaps not entirely safely by today's standards, by filling aisles and other empty spaces (for comparison, the official safe capacity is 2,752.)

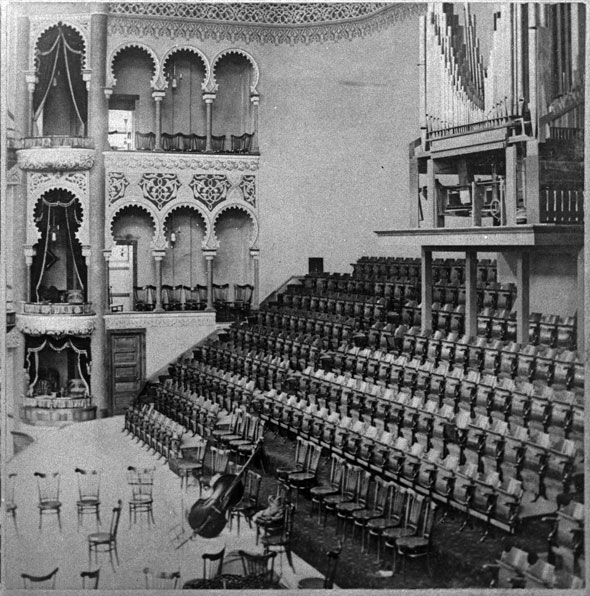

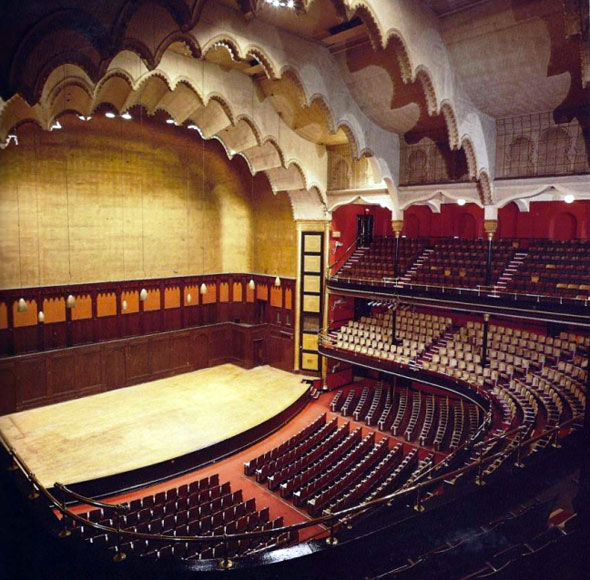

The auditorium featured stained glass windows, horseshoe balconies, and even a strange set of decorative Moorish-inspired fireplaces at the rear. The building was centrally heated by twin tubular boilers, manufactured in Boston, that forced steam through thousands of feet of pipe around the building.

The steam heated air was forced down from the roof on cold winter days with 30-horsepower electric fans. Cold air was pushed out through vents on the floor of the building so there was "a complete change of air every five minutes." In the winter, the system could be reversed to blow cold air.

From the ceiling hung giant gas and incandescent lights. Moorish arches and a massive built-in pipe organ were also among the original fixtures.

The hall wasn't without its detractors: according to historical notes from the City of Toronto, some residents felt Massey had skimped on space in order to save money, even though the final cost for the building was $30-50,000 over what Massey figured.

A lack of public gathering areas outside the main hall and a tiny backstage area are still issues the building grapples with today, ones that a proposed overhaul funded in part by money from the Massey Tower condos under construction nearby hope to remedy.

A few years later, in 1894, a small annex called the Albert Building was added to the south wall, behind the stage area. It originally served as a residence for the building's janitors but was later used as a vital, albeit small, extension of the backstage area and administrative space.

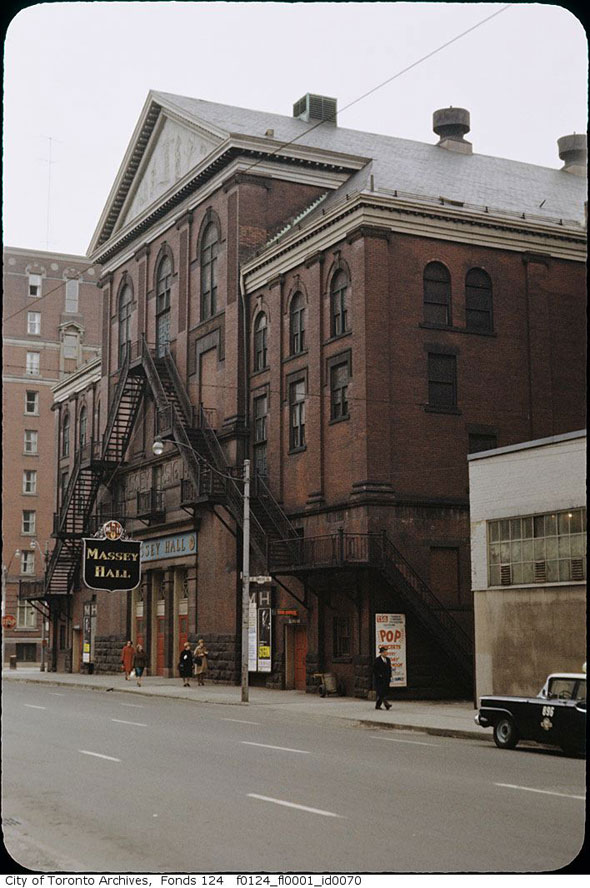

Interestingly, Massey Hall was without its now-famous exterior fire escapes for its first 10 years. The steps and ladders that zig-zag down the facade were added in 1911 to address fire safety concerns and a lack of emergency exits.

Massey Hall's outstanding characteristic was its acoustics. The Toronto Symphony and the Toronto Mendelsson Choir were the first residents of the hall, and its square shape lent itself well to warmth and depth. Performers standing at the edge of the stage can, apparently, generate unique reverb from the walls when singing a capella.

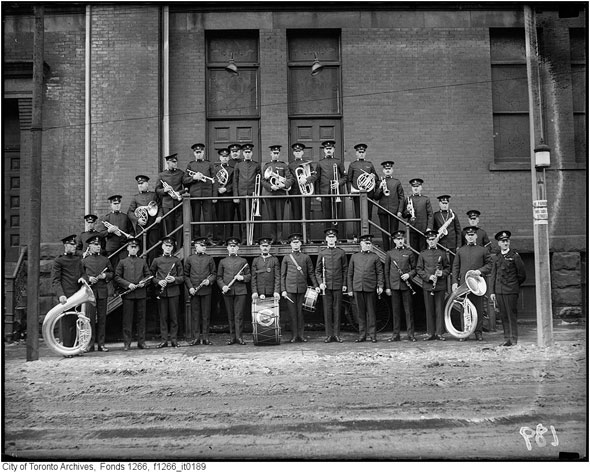

Groups like the Melba Concert Company, Varsity Glee Club and the Salvation Army choir all held performances at Massey Hall in the first few years. Ticket prices varied, but were usually between 25 cents and a dollar depending on the location of the seats.

As one of the highest capacity venue in the city, Massey was also used for speeches, meetings, and other important gatherings: everyone from striking railway workers to temperance advocates packed its more than 3,000 cushioned oak seats in the early years.

The temperance movement was a significant part of the building's history: all alcohol was banned on the premises for the first 100 years until the construction of the basement bar, "Centuries," in 1994. The lowest level was originally split in two, with room for 1,000 people according to the architect's specifications, and used for rehearsals and other meetings.

Massey Hall's most famous concert took place on 15th May, 1953. That night jazz legends Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and Dizzy Gillespie were preparing for a concert backstage. Just over the street at the Silver Rail, Charlie Parker was knocking back a triple whisky - too nervous to join the group without the help of a stiff drink.

When he finally did cross the street and slip inside the back door of Massey Hall, the concert he played with his four companions that night is still widely considered seminal in music history. Never again would this dream line up appear on stage again, let alone in a venue as acoustically rich sound as Massey Hall.

The rich sound has also inspired several live recordings. Neil Young taped an intimate concert in 1971 featuring a set of unfamiliar songs that would eventually become Live at Massey Hall.

Young was still recovering from a painful slipped disc during the concert, as referenced in some of the chat between songs, and there was some debate about whether or not to release the album straight away. In the end, Harvest would become his next solo record and the recording would sit on the shelf for more than 30 years.

Rush taped All The World's A Stage there in 1976; Ronnie Hawkins celebrated his 60th birthday by assembling a "Rock 'N' Roll Orchestra" comprised of Jerry Lee Lewis, The Band, and Jeff Healey. The tape of that concert came out as Let It Rock in 1995.

In honour of its status in the city, Massey Hall was designated a National Historic Site of Canada the 15th June, 1981. Among the features cited for inclusion on the register were the Palladian-revival style of architecture, red brick and stone detailing, and steel frame construction. Six years earlier, it had been officially protected under the Ontario Heritage Act.

Builders will have to be extremely sensitive to the these valuable features when they commence renovation work upon completion of the Massey Condos project. Only the Albert Building at the rear is scheduled for demolition, though the restoration of the brick front will mean the loss of the metal fire escapes many now consider part of Massey's character.

New offices and backstage areas for performers will be among the first additions to the venue since the 1890s. Architects have also imagined two "passerelles," glass walkways that will hug the sides of the hall, improving access, something the philanthropic Hart Massey would surely love.

MORE IMAGES:

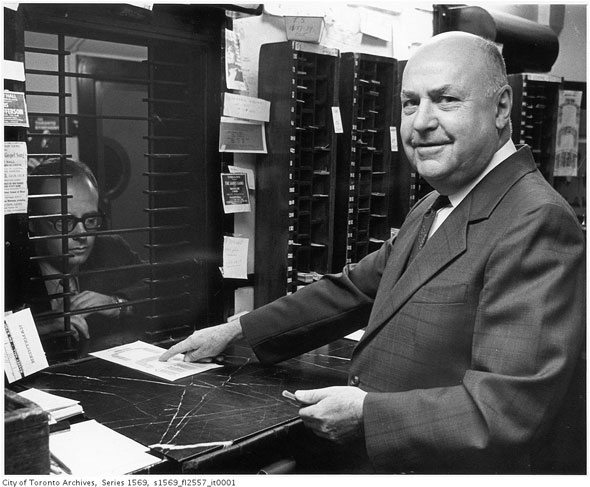

Manager Bud Connacher in the ticket booth at Massey Hall

Manager Ross Creelman poses with mover Jack Hughey while delivering a harp.

Tommy Gaw changes a stage light

A decorated Massey Hall exterior

Architectural cross section of the concert hall

One of the unusual fireplaces at the back of the main auditorium

The Toronto police band pose outside Massey Hall

The view from the stage in 1993.

An orchestra on the stage at the south end of the auditorium

Striking railway workers from the stage

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives; Globe and Mail; Toronto Public Library; Library and Archives Canada

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments