That time Toronto opened the Don Valley Parkway

52 years ago this month, a herd of eager motorists took excitedly to the first completed section of the Don Valley Parkway from Bloor Street to Eglinton Avenue. The road, designed to be a rapid and scenic connection between the new Gardiner and 401 highways, was touted along with the Bloor-Danforth subway as a proud testament to the power of the new Metro level of government.

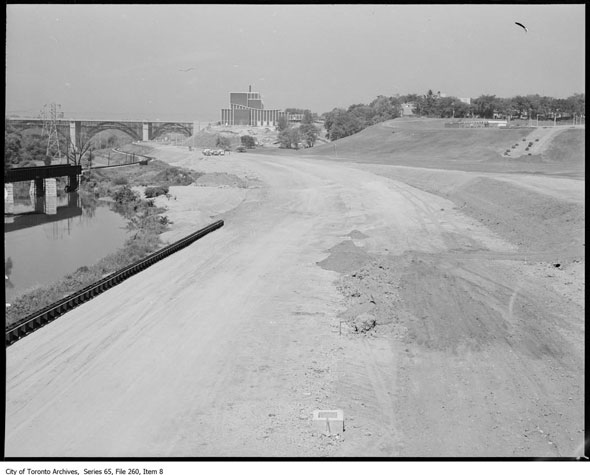

To get it built, engineers would have to drastically reshape what was already a heavily altered and overtaxed river valley while navigating existing bridges and inconvenient geographical features. Driving in Toronto would never be the same again.

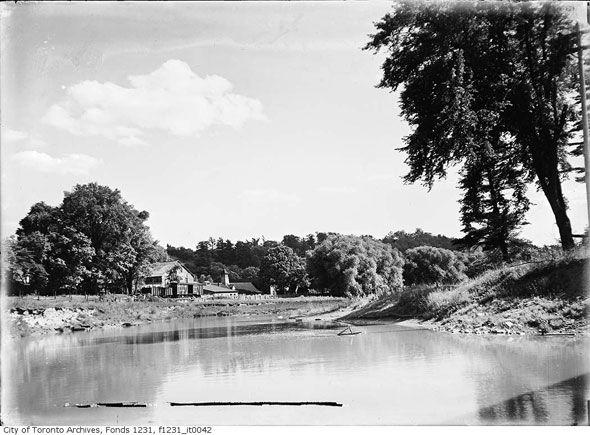

The Don Valley might seem like a relatively natural oasis from the a perspective on the popular biking and walking trail that winds between the rail tracks and roaring highway, but really few of Toronto's ravines have been more extensively manhandled and reconfigured over the last 150 years.

As described by early settlers, the Don River meandered the full width of the valley and was lined with dangling willow trees. Periodic islands in the water, the largest of which was just north of Queen Street, made ideal skating and canoeing destinations. South of present-day Eastern Avenue, the water fractured in to hundreds of small creeks as it entered a extensive marsh and eventually the sheltered waters of the Toronto Harbour.

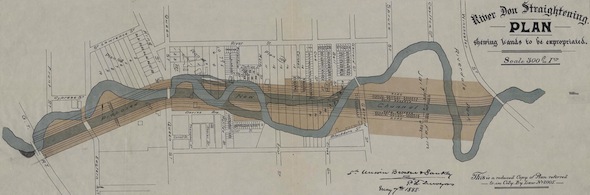

In 1886, the stretch of river south of the Prince Edward Viaduct was tamed and straightened from its original course in one of the first major engineering projects undertaken in Toronto. The costly action was an attempt to solve the "Don problem," a perception that the marsh at the mouth of the river was unhealthy and the winding curves were an impediment to industrial boat traffic.

As such, an entirely new 14-foot deep, dog-legged channel, lined with cedar, rock elm, and white pine timbers, was dug for the Don and the original course of water filled in. When it was finished, the ruler-straight river provided new space for railway lines and, almost a century later, Toronto's first (and only) fully-realized Parkway.

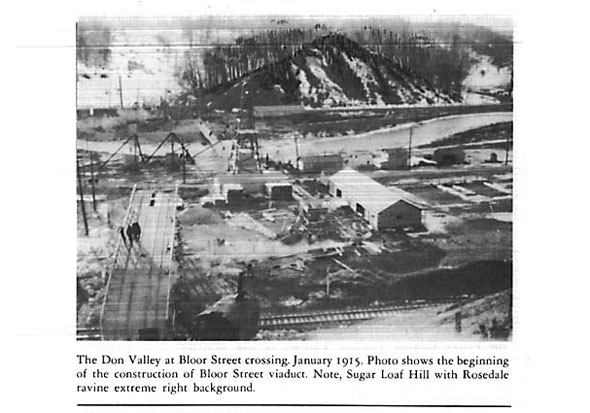

Construction of the road and extension of Bayview Avenue required the removal of several notable features of the Don Valley, including Sugar Loaf Hill, a large cone-shaped eminence located just north of the viaduct on the west side of the valley.

"The visitor who glanced down from the ramp of the viaduct, sees the top of the hill almost level with the floor of the bridge," Charles Sauriol, a naturalist who wrote several books on the valley, wrote in his book Remembering the Don. "The C.N.R. line flanks the hill on the east. North-westwards, a panorama of woodland (Old Drumsnab), becomes in summer a vista of undulating waves of billowy leafage extending towards Rosedale Ravine."

Sauriol also recalled a treacherous swimming hole in the shadow of Sugar Loaf Hill called Sandy Point, where river rapids moved quickly over soft sand and there were several drownings. It's not clear from his writing why people continued to bathe there if the water was so dangerous.

Another landmark, Tumper's Hill, located near the Don Mills Road, was also flattened and the dirt used as fill in the highway foundation.

The winding parkway was proposed in the mid 1950s by Metro Toronto in the hope of easing traffic congestion in the east end, a problem government calculated was costing $10 million a year in lost productivity and "weeks and months" out of commuters lives.

The original budget allocated for the project, which would be built in parallel to the southerly extension of Bayview Avenue, was $15.8 million. The "eastern gateway" to Toronto, as it was once dubbed, was seen as a panacea that would take heavy trucks off Kingston Road and provide capacity for the additional 25,000 people that were expected to arrive before 1960. The Don Mills development alone was projected to add 5,000 new faces.

Critics argued that spending $137.8 million (in today's money) on a highway was poor planning when many of the core's commuters arrived by transit. A rapid road link between the Gardiner and the new 401 would benefit relatively few and a subway along Queen to Bloor and the Danforth would be a much better way of tackling congestion, they said.

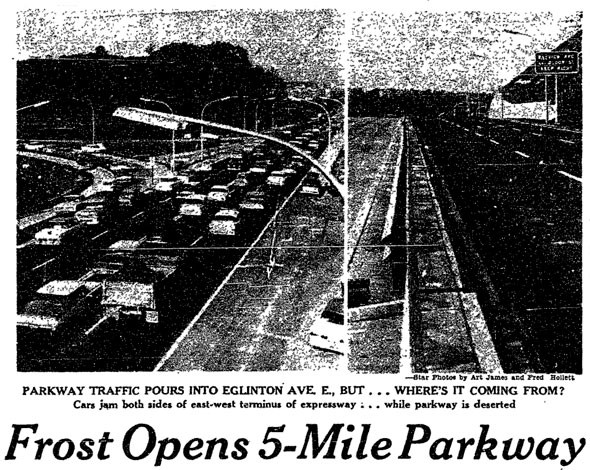

The original five-mile stretch of the Don Valley Parkway that opened on August 31, 1961 ran between Bloor Street, just north of the viaduct, and Eglinton Avenue. North and south of the termini work was already underway on additional phases that would reach the Gardiner and the 401.

The winding six-lane highway with its green median, one of the first transportation projects for the young Metro government, was designed to carry 6,000 vehicles an hour, up to around 70,000 a day when operating at full capacity (current traffic flow is around 100,000 vehicles a day, for comparison)

Opening day turned out to be something of a shambles once the formalities of opening the road were completed. A motorcade of dignitaries, including Premier Leslie Frost, Metropolitan Toronto chair Fred Gardiner, reporters, and police, traveled the length of the still-closed road lined with spectators and refreshment trucks.

Alderman Joe Piccininni was involved in the embarrassing first road accident on the DVP. While trying to execute a turn, he backed into the central guardrail and smashed one of his taillights.

At the opening ceremony, Fred Gardiner, who was already the namesake for a Toronto highway, joked the new road should be named the Leslie Frost Thruway in honour of the Premier. Perhaps luckily, Frost hated the idea, even in jest, saying he was "allergic" to having things named for him.

"It's no good for them to name anything after you when the roof falls in and the blinds go down," he said. "Recognition is better when you're alive."

Despite his wishes, Toronto now boasts the Frost Building at Queen's Park and York University the Leslie Frost Library.

In a few short minutes after the barricades were flung open to a line of eager motorists, the DVP rapidly became impassible. While the south end of the road at Bloor was almost completely silent - so few cars "I could have sat down in the middle of the road and boiled a three-minute egg," in the words of reporter Fred Hollett - the intersection with Eglinton was a parking lot.

The lopsided flow was attributed to the confusing temporary entrance at the Bloor Viaduct. Like today, drivers heading north used the Danforth side of the valley while motorists making the short (and pointless) hop south reached the road via a bridge over Bayview Avenue.

The delay went down as "one of the worst traffic jams in Metro history" despite being only a mile long and holding up most motorists a mere 20 minutes.

The impending opening of the stretch south to the Gardiner posed a big challenge for the central core. The additional cars required wider roads, additional traffic planning, and more parking spaces.

Engineers and town planners urged the city to build park-and-ride lots - pencilled in at the Bloor Viaduct, Gerrard and River, and King and Queen - with enough space for 5,000 cars that would be served by the TTC in an attempt to spare the narrow streets of the core from the worst of the traffic.

In a column in 1961, writer Ron Haggart warned of a "double loss" for the city if the lots and transit connections weren't built as they were originally conceived in 1955: congested roads and the proliferation of surface parking on prime land would prevail, he said.

The park-and-rides were of course never built. Instead, Toronto pushed ahead with the highway in sections between Eglinton and Lawrence, Lawrence and the 401, the 401 to Steeles, and south to the Gardiner with no links to public transit.

The final stretch - a short, quarter-mile hop from Sheppard Ave. to the 401 - was opened with little fanfare on April 6, 1967. Weeks earlier, the complex tangle of flyovers and slipways that connect the road to the east- and west-bound express and collector lanes of the 401 was finally completed after two years of construction work.

For the first time drivers could, in theory, travel downtown at an unbroken 90 km/h.

The traffic snarls didn't end, however. High levels of car ownership kept the pressure on the DVP and the cancellation in 1971 of the Spadina Expressway, the parkway's sister, ensured it remained the sole north-south artery for cars heading to and from downtown.

As it dawned on drivers that perhaps the road wouldn't be a cure-all, Toronto's chief traffic engineer Sam Cass tried to issue some reassurance, predicting traffic would "ease considerably" in the coming years as more connections were built.

"Until then - patience," he said.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library, Toronto Star

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments