Remembering the deadliest transit disaster in Toronto

This week's deadly collision between a Via Rail train and a double-decker Ottawa city bus has once again underscored the dangers of vehicle traffic crossing busy rail lines at grade.

While investigators are still searching for the cause of the accident, the tragedy has awful parallels with an accident in Toronto 37 years ago.

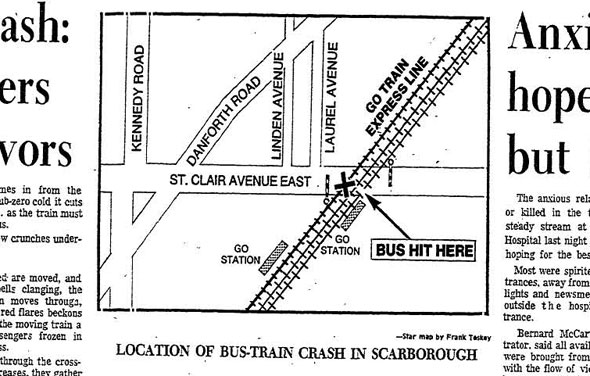

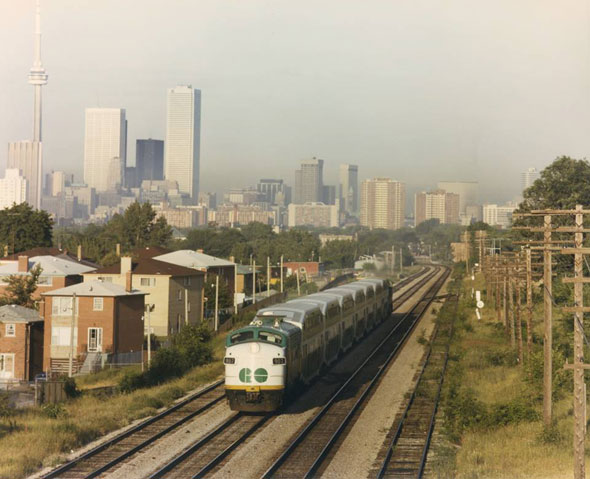

In the weeks before Christmas 1975, a packed TTC bus became stranded and was struck by a fast-moving Lake Shore GO train in Scarborough, near Midland and St. Clair Avenue East.

Toronto's accident was, and still is, the worst mass transit disaster in the history of the city in terms of its death toll. The subsequent investigation and coroner's report would lead to widespread changes in the way rail lines interact with busy arterials.

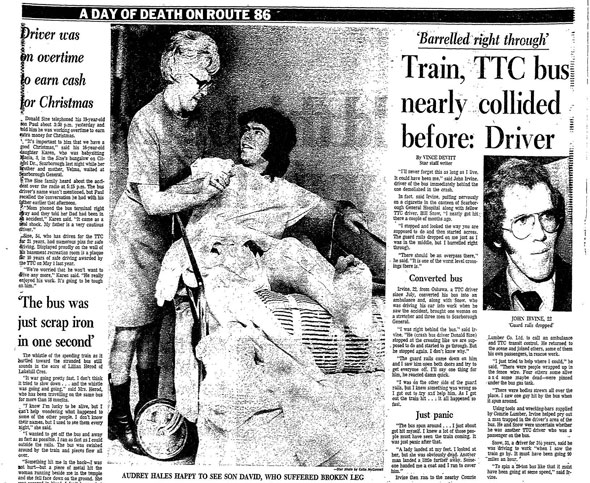

December 12, 1975 was cold and overcast. The temperature hovered just above freezing and the threat of icy rain and snow lingered in the air. On St. Clair Avenue East, TTC bus driver Donald Sine was at the wheel of a No. 86 bus, making his usual round trip from Warden station to Metro Zoo via Kingston Road and Military Trail.

Aged 54, Sine was a 22-year veteran of the Toronto Transit Commission. He had operated buses for the last 14 years and earned merit pins for safe driving. A year earlier, on May 14, Sine had received his 10-year certificate of appreciation from the TTC in "recognition of his outstanding record of safe driving" over the last decade.

As usual for a Friday evening, bus 8044 - a brand new General Motors "fishbowl" model - was packed with rush hour commuters recently released from the subway. Christmas was a little over a week away, and the 65 regular passengers, familiar in each other's company, chatted as the vehicle rattled toward a level crossing at the GO tracks just beyond Kennedy Road.

The crossing, like others in Toronto, had been controversial for years. While subways and underpasses had been built to separate downtown traffic from busy train tracks, outside of the core the same lines regularly crossed major roads at grade.

Local residents and councillors, fearful of an accident at the busy St. Clair East crossroads, had been demanding the road be diverted beneath the rails for years, but federal funding had ben slow to materialize.

"We applied for the project last February 12," Metro Chairman Paul Godfrey told the Toronto Star at the time. "I have written to the transport minister, every member of Parliament, and spoken to (former transport minister) Mr. Marchand about the four or five grade separations needed in Metro."

That December, all that separated the roaring diesel GO and CN freight locomotives from the heavy rush hour vehicle traffic was a set of automatic wooden barriers.

At the last stop before the rail crossing, Leda Gulis, a 36-year-old newcomer to Toronto on her way home to help her 10-year-old daughter decorate the family Christmas tree, remembered the rear door of the bus became jammed closed, stopping people getting off.

Donald Sine called back from his seat to ask riders to open and close the door by hand, which they did, according to Gulis.

Moments after the bus was back in motion, the stuck rear doors suddenly popped back open, drawing giggles from passengers near the back of the bus. Sine tod two young boys to get off the automatic step, but no-one was there.

The bus slowed, its automatic brakes activated by the open doors, and witnesses remember the veteran driver fiddling with the electrical control panel. The bus was straddling the southbound GO train tracks when warning lights came on and the safety barriers eased downward.

"Don't panic," David Hales, a computer operator at Queens Park riding at the back of the bus remembered Sine calling out.

What happened over the next few seconds was a blur to the passengers on the bus. Some people, realizing their perilous position, began to file from out of the bus and gather on the tracks beside the stranded vehicle.

When the horn of the GO train sounded, the mood immediately turned to panic. "Everybody out," Sine yelled, but not everyone could hear in the crush towards the doors.

The driver jumped from his seat and out the front of the bus. "We saw the train coming and there was a little bit of panic, with a lot of people pushing and shoving," remembered passenger Dag Greeven.

GO train driver Patrick Gartland and second engineer Lorne Holder were traveling at 112 kilometres an hour at the first sign of trouble, having just passed a similar at-grade crossing at Midland Avenue. Donald Sine was running toward the train, arms waving, as his bus lay stricken, surrounded by a crowd of people.

"We'd better soak her," Holder called, using a technical term for shutting down the engine.

Gartland immediately threw the emergency brake, unleashing a deafening screech as the wheels dragged across the polished steel rails. The train lurched and juddered violently as its standing passengers fought to regain their balance.

Back at the bus, confusion reigned. Witnesses would later recall that some people thought the train was on a different track while others fled for the road. Several passengers stood on the tracks behind the bus, unable to see the looming train.

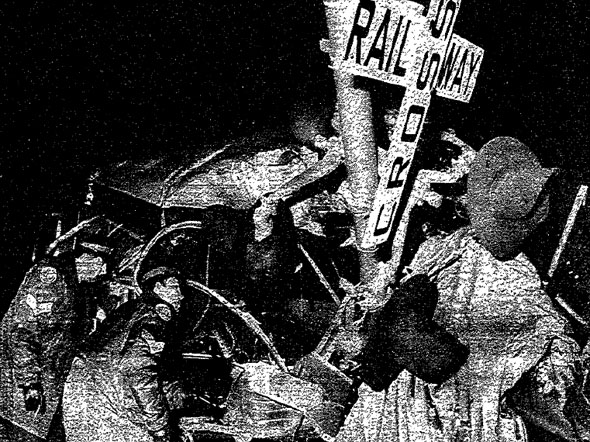

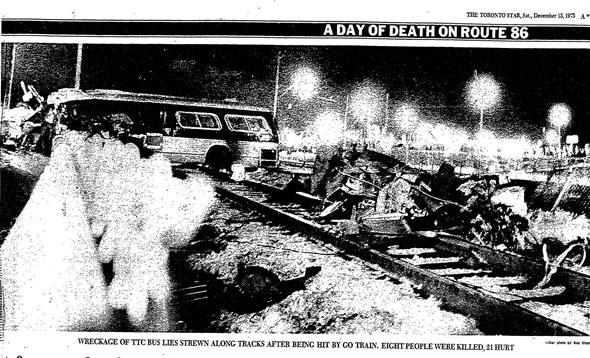

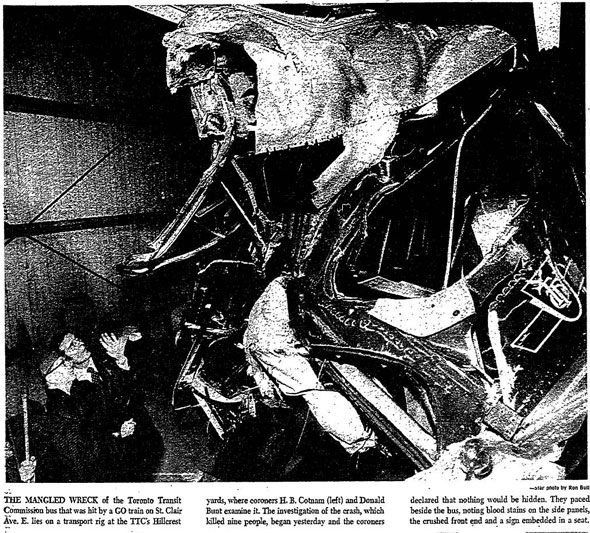

Sine stepped out of the train's path at the last possible second. He watched as the green 236-ton locomotive screamed past at 80 km/h and slammed in to his half-full bus, tearing it in half. Shreds of aluminium, dust, and bodies were scattered by the impact and part of the vehicle was dragged down the track.

John Irvine, the driver of the bus following Sine's, had been calling passengers to safety until the moment of impact. "A lady landed at my feet," he said. "Obviously she was dead. Another man landed a little further away."

"I've never seen anything like it in 15 years of nursing," off-duty nurse Barbara Hollness recalled of the accident, which happened just metres from her St. Clair Avenue East home. "I had to fight to compose myself."

Hollness, like dozens of witnesses, were drawn to the scene of the accident. She attended to a woman in her 50s with compound fractures to her legs who asked that they pray together while firefighters applied an oxygen mask and a pressure bandage to her head wound. Close by, Hollness' husband Ed helped with the bodies as the growing dusk turned to night.

There were eight in all, four of them beneath the crushed remains of the rear section of the bus. The men and women ranged in age from 19 to 66. They were Margaret Andrejek, 19; Joan Mich, 40; Wendy Gamey, 20; Renato Diano, 30; Leo McCale, 29; Frank Lederer, 42; Edelle Petersen, 48; and William Stride, 66.

Hundreds of bystanders looked on from the crossing gates, their collective misty breath visible in the spotlights set up by rescue workers. The glow of the red emergency flares wielded by police officers danced on their faces. No-one spoke.

Donald Sine was in shock. "I tried, I tried," he muttered as he surveyed the scene. He had been working overtime to raise extra money for his wife and three children to enjoy at Christmas.

The 16 injured were taken by ambulance to Toronto East General Hospital, where they were treated for a range of injuries, some severe, some mercifully minor.

"It was a sea of injuries ... like war," said Dr. Ed Moran, a general practitioner on duty that evening. His quiet emergency room at the hospital was transformed in moments by the flood of ambulances.

"I stood there for a moment. My first major impression was one of indecision. Should I blow the whistle and call out the whole team? What if it turned out to be a few sprained ankles?" Moran made the call - five surgeons, the only ones on duty, were immediately summoned to the ER and worked late in to the night stitching wounds and resetting bones.

65-year-old Leslie Levin, riding the bus after staying late at work, died a short time after his arrival, becoming ninth and final victim of the crash.

The immediate legacy of the Christmas tragedy was increased urgency for grade separations on major roads. Five days later, Ottawa pledged the $5.2 million needed to build underpasses on St. Clair Avenue East and Midland Avenue, just down the tracks. Funds for similar bridges at Eglinton East, Kennedy Road, and Islington Avenue were also sought.

Sine was hailed as a hero for his attempts to restart the bus and flag down the approaching train, an honour he consistently rejected. "I'm no hero ... I did the best I could," he told the Star. "I don't feel heroic because nine people died and that is terrible, really awful."

The TTC made changes to the electrical systems in its 8000 series buses after a leaked preliminary report from coroner Dr. Donald Bunt suggested the brakes on the vehicle, which were programmed to automatically engage when the doors are open, may have been to blame for the bus becoming trapped.

The accident spooked TTC drivers, too. A report a month later revealed that bus operators were breaking official guidelines by refusing to stop at the crossing due to poor visibility and the unusual width of the tracks. Starting a bus from stopped and getting it across the five sets of rails took too long, they said.

When the coroner's verdict arrived in March 1976, it blamed a variety of failings at the TTC and CN, the operator of the GO trains. A switch that could have released the stuck brakes had been purposely moved out of the driver's reach to prevent "irresponsible" operators moving with the doors open. The TTC had neglected to mention the change to its staff.

The emergency brakes on GO trains were also scrutinized. It took the packed commuter 1.2 kilometres to reach a full stop, and the verdict recommended slower speeds and longer warning times for approaching trains at level crossings.

Dr. Bunt accepted that a wiring fault near the control switch for the automatic braking system was to blame for the bus stalling. The coroner took time to praise the actions of driver Donald Sine in his verdict.

Today, St. Clair Avenue East passes under the GO tracks via a concrete underpass completed in 1977.

Toronto Star, WikimediaCommons, City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments