That time Eaton's planned the tallest tower in the world

Toronto has had its fair share of aborted construction projects and big development ideas brought low - enough to fill two fascinating books, in fact - but Eaton's John Maryon Tower, a giant precursor the the CN Tower, is perhaps the biggest project (literally) to never get off the ground.

Planned to replace Eaton's College Street store, the tower would have bested even the World Trade Center towers in New York for height and would still be the fifth tallest building in the world (if like the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat you exclude the likes of the CN Tower, which has few real floors.)

It's perhaps fortunate for fans of College Park that the giant triangular monster never seriously got going.

Despite its grand, imposing presence, the Eaton's Art Moderne College Street store was never quite as impressive as the company had once hoped. The original proposal for the the company's second major Toronto store called for a 36-storey, 204 metre tower that would have risen from the centre of a sprawling store covering the entire block bound by College, Yonge, Bay, and Hayter.

As Mark Osbaldeston notes in Unbuilt Toronto, the building would have been second in height only to New York's Rockefeller Center, then still in the concept phase and one of the largest private enterprises ever undertaken.

T. Eaton Co. had spent the early part of the 20th century gobbling up land on the east side of Yonge, north of Carlton, west of Church, in anticipation of Toronto's commercial district shifting north to what was then midtown. The land grab was kept top secret, leading to speculation CPR was planning to build a massive new train station and run tracks underground to Davisville.

In the end, Eaton's opted to build its new flagship store on a second plot of land it had bought around the same time on the southwest corner of Yonge and College. The ambitious set of blueprints were drawn up by Ross and MacDonald and Sproatt and Rolph, two architectural firms that had previously teamed up to produce the Royal York Hotel.

It would have been the largest department store, maybe even the largest building in the world, butjust as the Depression put paid to grand plans for University Avenue, the financial downtown similarly decapitated Eaton's skyward development. The planned main tower was shifted around on drawings until it was lopped off entirely, along with several floors.

The Eaton's store that was finished in 1928 was only seven stories, though it did manage to retain much of its grandeur and some of its finest design touches, including the top-floor event space now known as The Carlu.

Perhaps in the hope of reviving the tower, Eaton's had the foundations sunk into the bedrock behind the store just in case.

Though its first attempt had come a cropper through lack of money, Eaton's clearly never gave up on its high-rise dream for College Street. In October 1971, the company announced it wanted to build a new office tower - the tallest in the world, no less - and knock down its College Street outpost.

The John Maryon Tower, as it would later be known, was to be 503 metres and 140-storeys high - taller than Malaysia's Petronas Towers, finished in 1998, the Willis Tower in Chicago, and New York's original World Trade Center towers.

The department store had been itching to redevelop its downtown holdings since the 1960s when it first pitched the Eaton Centre as a cluster of separate towers. That original proposal assumed the demolition of the Church of the Holy Trinity and Old City Hall, though it later revised its proposal to include the clock tower of Toronto's former civic heart.

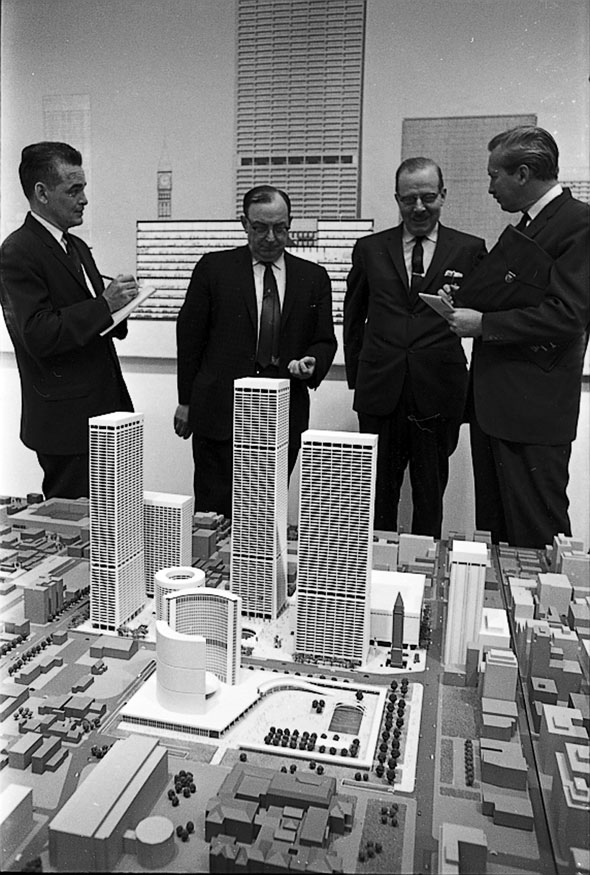

A model of the triangular concrete, steel, and glass John Maryon Tower was officially unveiled by its engineer namesake at the CNE's International Building Exhibition that year. Maryon was an expert in tall buildings and and President of John Maryon & Partners Ltd., the company behind the Bell Aliant Tower in Moncton.

The tower he designed would have been built on the vacant lot behind the Eaton's store and the original demolished to create an expansive approach from the north. Its unusual shape would deflect winds of up to 200 km/h, Maryon said, and help it stand for "1,000 years." Two small pavilions, in a similar shape, were drawn just to the north.

Office workers would have been tapping away on Selectric typewriters in the building's 265,000 square metre interior while a 183-metre rooftop radio mast ensured TV viewers in Toronto received a crystal clear picture. One of the benefits to the CN Tower, built two years later, was the ability of its antenna to transmit UHF, FM, and AM signals over new downtown skyscrapers.

In the Toronto Star write-up of the announcement, it was noted the Maryon Tower would have been more than twice as tall as Commerce Court, then under construction at King and Bay on its way to becoming the Commonwealth's tallest building.

As revealed at the time, the development was dependent on T. Eaton Co. receiving permission to demolish its original store, the Eaton's Annex, and its other buildings north of Queen Street for the Eaton Centre.

The revised proposal that offered to leave the clock tower of Old City Hall marooned in the centre of a concrete plaza was panned by Toronto residents and the company was forced back to the drawing board again, delaying construction on the centre for several years.

The company would eventually get its mall but the John Maryon Tower was less fortunate. Interest in the development petered out not long after it was proposed as demand for new office space dwindled. The handful of public drawings released in 1971 were filed away for good in the dusty drawer reserved for lost Toronto developments.

Despite its dormant status, the company confirmed it was still weighing the project next year in 1972. Announcing the news, Toronto Star columnist Alexander Ross called the prospect of the monumental tower "insane urban planning."

A series of financial setbacks in the late 1970s severely hobbled the nationwide company. A spin-off chain of smaller department stores named Horizon failed and was closed down while several other Eaton Centres in cities like Sarnia, Guelph, and Peterborough struggled with low occupancy rates.

The company finally went bankrupt in 1999 and was bought by rival Sears for $50 million. Serendipitously, the plot of land that was to be used for the John Maryon Tower is now the site of the Aura condo, which will be a whopping 272 metres tall when it's finished next year - barely half what Eaton's had once planned.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Toronto Telegram, Ontario Archives, The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments