That time Canada's "birdman" crashed in Toronto

John Alexander Douglas McCurdy - J.A.D. for short - was Canada's first licensed airman and the first person in the British Commonwealth to make a controlled ascent in a powered flying machine.

At age 25, in 1911, the fearless Nova Scotian became the first pilot to attempt a massive 160-kilometre ocean crossing in a basic, single-engine wooden aircraft. He was just moments from land when an oil leak - dripping unseen since take-off - forced an emergency landing in shark-infested Caribbean waters.

Despite this and several other wrecks, one of them in a farmer's field near present day Don Mills and Eglinton, McCurdy went on to play a pivotal role in Canada's young aviation industry and would eventually become the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia.

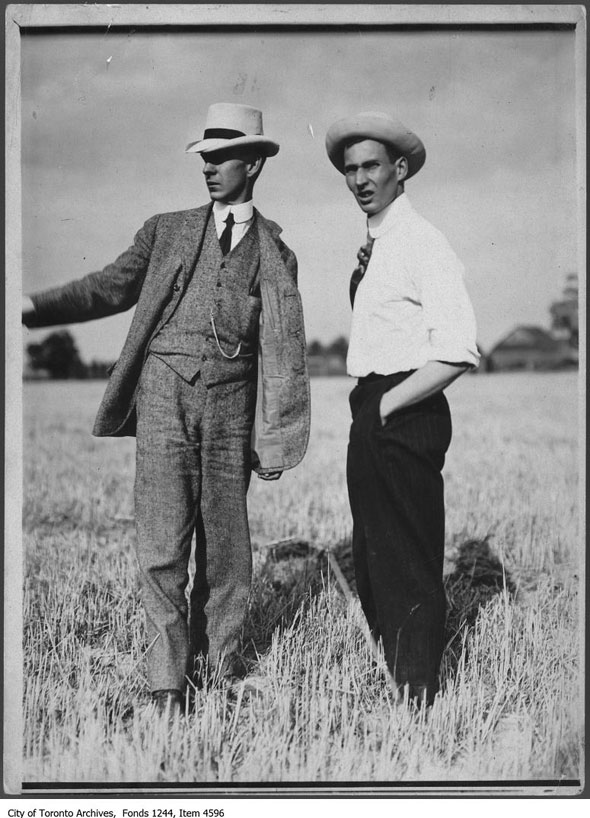

The son of an assistant to Alexander Graham Bell, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (above left) was born in Baddeck, Nova Scotia in 1886. He studied at the local academy and grew in to a handsome, well-postured young man. He had a square jaw, deep brown eyes, and a calm, unflappable personality.

As a teenager, his natural aptitude for math and mechanics, inherited from his father, landed him a spot in the engineering program at the University of Toronto, where he was to be found studying in the early 1900s.

Back in Baddeck, Alexander Graham Bell was spending his days outdoors conducting thousands of flight experiments at the foot of a gentle slope on his Beinn Bhreagh estate. In the years after securing his telephone patent, Bell had come to believe mastering powered flight was of great national importance.

"The nation that secures control of the air will ultimately rule the world," he wrote in 1908. Though he took his tests seriously, setting up blackboards and meticulously recording flight data, the names of his early contraptions were often ridiculous - "Codger," "Frost King," "Cygnet" - and often resembled kites, each one with a different configuration of cells and airfoils for generating lift.

"He goes up there on the side of the hill on sunny afternoons and with a lot of thing-ma-jigs fools away the whole blessed day, flying kites, mind you ... these kites and queer machines he keeps bobbing around in the sky. Dozens of them he has ... It's the greatest foolishness I ever did see," a confused neighbour is quoted as saying in a biography of Bell.

As the designs grew larger, Bell graduated from lighter-than-air kites to powered machines that required a pilot, someone with excellent technical knowledge and no fear of being high in the air a simple wooden aircraft with canvass wings.

J.A.D. McCurdy was a fearless youngster, and Bell recruited him and three other like-minded young men - Frederick Walker Baldwin, Glenn Hammond Curtiss, Thomas Etholen Selfridge - on the advice of his wife, Mabel Bell, with a mind to forming an association in 1907.

The goal of the Aerial Experiment Association was simple: "get in the air."

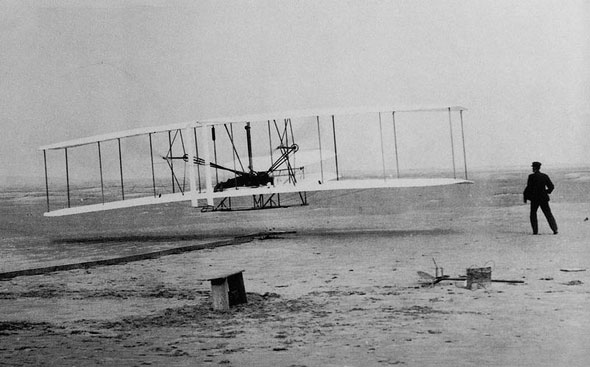

The team didn't know it, but Wilbur and Orville Wright had already claimed the prize for the first controlled, powered flight several years earlier during a secret experiment at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina. The AEA persisted a short time with kites but moved to fixed-wing aircraft after an accident that dropped Selfridge from the sky into a freezing ocean.

Their first successful flight of a powered aircraft took place in Hammondsport, New York on 12 March, 1908. The plane, named the Red Wing, flew a handful of times for about a week before it was destroyed in a crash. For the plane's successor, White Wing, Bell added flaps that could control the air flow over the wings, which he named ailerons. The plane also had wheels on its undercarriage for take-off and landing.

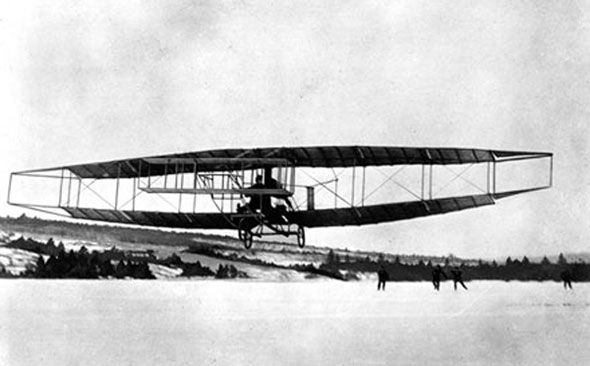

Bell and his young team won a competition held by Scientific American with their third plane, June Bug, which completed 150 flights. The Silver Dart was the AEA's fourth plane and the one that would claim a record for Canada and the British Commonwealth.

When J.A.D. McCurdy, the aircraft's designer and lead engineer, fired up the rotary engine, accelerated to 65 km/h along the frozen surface of Bras d'Or Lake, and glided into the biting winter air he became the first British subject to fly anywhere in the Commonwealth.

For his feat, the British government awarded him its first ever pilot's license. It was February 1909.

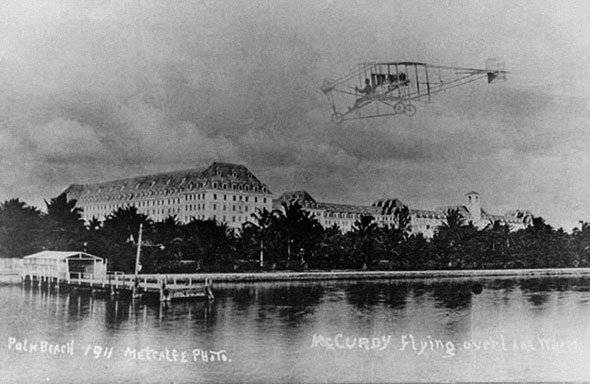

The AEA didn't last much longer but McCurdy continued to fly. In 1911, after years of unsuccessfully lobbying the Wilfred Laurier government to fund his endeavours, the aviator prepared to make a pioneering ocean flight from Key West off Florida to a field about four miles outside Havana, Cuba, a distance of around 170 kms.

McCurdy had been lured south by the promise of an $8,000 reward from the city of Havana and The Havana Post for successfully completing the crossing.

No-one had tried such a flight before and McCurdy's preparations drew rapturous attention. Government offices and local businesses closed so that workers could see the courageous Canadian depart. Rooftops and other vantage points were packed with spectators on the clear, hazy morning of the "most ambitious point-to-point feat ever attempted by an aeroplanist."

The U.S. Navy had taken an active interest in the flight and positioned a succession of torpedo boats to guide the plane - equipped only with a compass - toward Cuban soil; in case of a crash landing, McCurdy had had special pontoon floats attached to the wings.

Bad weather had hampered the attempt for six days, leaving McCurdy and the locals frustrated, but favourable winds and sea conditions arrived on the seventh day and the team decided to make their attempt.

With his final checks completed, McCurdy's engineer gave the propellor a couple of twists and the engine roared to life. After a quick wave goodbye, the biplane skimmed along the smooth sand and effortlessly up in to the clear sky. He circled the island at around 1,000 feet, passing above the local wireless tracking station, before turning and heading out over the water towards Sand Key and the first ocean waypoint.

The view was unlike anything anyone had ever experienced: electric blue water beneath an electric blue sky. The lack of clouds or landmarks made it hard for McCurdy to orientate himself and contributed to severe spatial disorientation, a problem that still troubles pilots today.

"As I left the sand wastes of Florida skies behind, I was amazed to find the sea confronting me instead of below me. I beheld a mirage not as seamen see this phenomenon, but as though I was part of it," he recalled.

Guided by compass and puffs of steam Navy ships, McCurdy was in touching distance of his goal when the engine, located directly behind him, began to make "a terrific noise" - it was dying of an oil leak that had gone unnoticed on the ground in Key West. The Cuban crowd on the shore watched as the little plane gradually lost height and splashed into the ocean, just shy of land.

The U.S.S. Pauling arrived in minutes and plucked the uninjured pilot from his seat just as sharks had begun to circle the bizarre contraption. The accident clearly didn't trouble the unflappable McCurdy. He opened his story in the Star by complaining about the attention from the "impressionable" Cubans following his soggy arrival.

Later that week at a special gala event in his honour, Cuba's president José Gómez handed McCurdy an ornate red and green envelope amid the opulent surroundings of Havana's opera house. It was empty.

McCurdy was later advised by an American diplomat to ignore the bizarre exchange and forget his prize, which he did without apparent fuss.

Eight months after his dunk in the salty waters of the Caribbean, McCurdy flew the repaired plane from Hamilton to Toronto for the city's second annual aviation meet at Donlands Farm near Todmorden Mills.

Organizers built a grandstand for spectators and special passenger trains were organized from Union Station so people could witness the thrill of flight, which was still a dizzying novelty.

McCurdy arrived the day before, bumping down on Fisherman's Island, which was once located near today's Cherry Beach. The 56 kilometre journey took just over half an hour and allowed McCurdy to penetrate the thin air at 3,000 feet.

"The smoke was so thick over the city I couldn't see as far as King Street," he recalled over drinks in the King Edward shortly after landing. "At the eastern end of the Island I was flying so low that I was skimming over the heads of people in motor boats, and also over some tents and campers on the shore. They seemed to be quite excited. I circled back around Hanlan's Point and finally made my landing on Fisherman's Island."

Both McCurdy and fellow pilot Charles F. Hubbard made the journey to Toronto for the meet. Hubbard's aircraft, a "monoplane," had arrived earlier that day and both were boxed up and shipped over land to Donlands Farm.

Shortly after dinner on a gloomy summer's evening, McCurdy's plane was wheeled out from its tent where engineers had spent the afternoon overhauling the Gnome rotary engine. The weather was miserable, but a crowd still watched eagerly from the stands as the motor was yanked to life and McCurdy prepared for flight.

Released by his crew, McCurdy bumped down the uphill dirt runway, hopping in to the air and falling back down. It soon became clear the pilot was struggling to achieve take-off speed and a row of parked cars lay shortly ahead. Moments later, the little plane lifted a few feet off the ground, rolled left on to its back, and landed with a crunch in a freshly ploughed area just off the landing strip.

The grandstand emptied as spectators ran to the scene. They found McCurdy miraculously unhurt, surveying his wrecked plane. Gasoline leaked from a punctured fuel tank and the tail section had been destroyed. "It was all the fault of the runway," he said.

The $2,000 frame was a total wreck.

McCurdy flew until 1916 when vision problems kept him permanently grounded. His involvement in Canada's early aviation industry continued, however. He founded and was the manager of Long Branch Aerodrome pilot training school and helped set up Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd., an aircraft manufacturer based at Dufferin and Dupont that built planes during the first world war.

He died in 1961 after a five-year spell as Lieutenant-Governor of his native province.

MORE IMAGES:

Another view of McCurdy's wrecked plane at Donlands Farm

McCurdy flying in Toronto

A Curtiss Canada bomber - the first two-engine airplane made in Canada - at Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. McCurdy is in the cockpit on the left.

A group of aviators. J.A.D. McCurdy is second from the left.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Library of Congress

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments