That time Toronto hid a flying saucer

Toronto has seen its fair share of bonkers contraptions over the decades. From Knapp's Roller Boat, a cigar-shaped Victorian ship its designer hoped would drive over the top of choppy water (it didn't,) to the proto-hot air balloon launched by a German aviator on Front Street in 1859, the city has never been starved of spectacles.

The Avrocar, an awkward hovering patrol vehicle with supersonic fighter ambitions, built and tested in secret at Malton during the Cold War, might just trump them all for peculiarity, if not practicality.

A.V. Roe Canada Limited, as it was first known, was a Canadian subsidiary of British engineering firm Hawker Siddeley. It was formed by the merger of Hawker's existing aircraft division, named for its founder, Alliott Verdon Roe, with Victory aircraft, a Canadian plane maker based at Malton airport, now Pearson.

At Avro in 1952, visionary English designer John Carver Meadows Frost - "Jack" Frost to his friends - was the project designer on the company's high-speed interceptor jet, the CF-100 Canuck.

The "tall, gangly" Frost arrived in Canada from de Havilland, a British aircraft maker at its peak during the second world war, where he contributed to the company's search for a supersonic fighter plane and was lauded for his useful problem-solving tweaks.

The CF-100 was the first military jet wholly designed and built in Canada, but its creation had been fraught with problems: a serious issue with the wings flexing dangerously during flight had led to two crashes. As a result, completed planes were delivered late and the company was heavily criticized by the Canadian government.

In the resulting internal shuffling, Frost was re-assigned by his superiors to head up the Special Projects Group - Avro's top secret skunkworks division where radical innovations were nurtured away from prying eyes in a special workshop at Malton.

"Guards on the door, locked doors, special passes ... we were not exactly ostracized but we played our own little tune in the corner of a very large company," Al Wheelband, one of the group's engineers is quoted as saying in author Bill Zuk's "Acrocar: Canada's Flying Saucer."

The first suggestion Frost was dreaming of a flying saucers had come the year before, in 1951. Without warning, the Frost approached shop superintendent Bob Johnson and asked him to fabricate a disc 9-cm wide, 2-cm thick with small scoops carved around the edge. At the centre he needed a hub, like a bicycle wheel.

He told Johnson it was part of the CF-100 project, but refused to elaborate.

After a series of tests in which Frost dazzled workers by making the little disc fly around the room using a jet of compressed air, the designer presented a rough concept for an aircraft with vertical take-off and landing capabilities to Avro management.

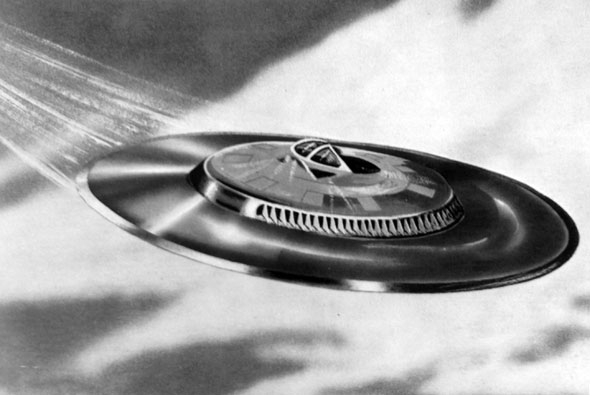

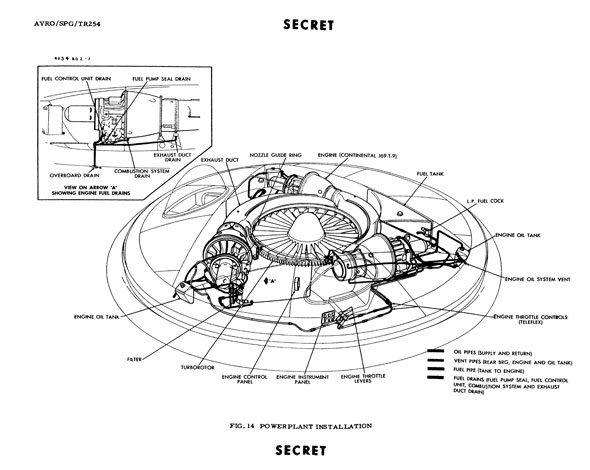

Codenamed "Project Y," the central feature of the Avro flying saucer was a special flat engine capable of lifting itself off the ground by propelling its thrust in a circle.

The first full-size mock-up, financed by Avro with an eye to producing a working fighter jet, dispensed with the early frisbee shape and looked more like the blade of a shovel. Nicknamed "Flying Manta" and "Stingray," it was 7.8 metres long, 6.4 metres wide and could, in theory, reach speeds of up to 2,400 km/h, according to wind tunnel calculations.

Two natural phenomena made the underlying principle viable: The Coanda or "ground" effect, which causes a jet to be attracted to a nearby surface, and the ground cushion effect that generates increased lift and drag on airplane wings when they are close the ground.

Engineers in Britain helped with research and development, but Project Y was still highly classified. Design tweaks were made on scrap paper and immediately destroyed but the cloak and dagger tactics couldn't stop people talking, and the Toronto Star jumped on the story when it eventually leaked.

"Takes off straight up: report. Malton 'flying saucer' to do 1,500 mph," read the headline on Feb. 11, 1953. "A wooden mock-up reported to lie behind tarpaulin screens in Avro Canada's experimental hangar at Malton, to which only holders of 'super-security' cards are permitted."

"No project of this kind is known to be under development elsewhere in the Western world."

Despite promising results in the wind tunnel, the Canadian government balked at the $100 million Avro estimated to fully develop the craft and pulled out entirely, having sunk about $2 million on development.

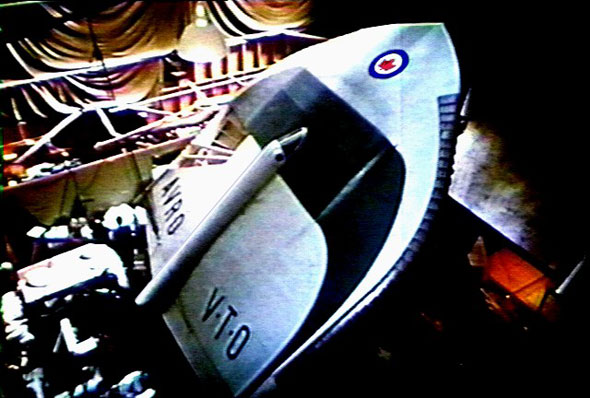

However, the American military had already inspected several prototypes of the aircraft, which was now circular again, and stepped into the breach.

The U.S. Air Force agreed to finance Frost's design in 1954 to the tune of $784,492, extending its development until 1956 and opening up wind tunnel and test facility access in Ohio and Massachusetts.

Now all Avro had to was build the thing.

A special indoor rig was erected at Malton to test various engine configurations as Frost realized early on a single engine would not be capable of generating enough power for lift and supersonic flight. Due to the thrusts and speeds involved, observers had to be sheltered behind a quarter-inch steel wall with little windows - it was a good thing, too.

During an indoor trial run, one of the engines caught fire and began to accelerate out of control. Frost and the team fled but were spared from disaster by a quick-thinking engineer who hit the fuel cut-off switch on his way out.

While Frost was trying to get his aircraft off the ground, the U.S. Army expressed an interest in doing exactly the opposite.

The U.S. had already spent more than $1.7 million in search of a viable design for an "air jeep," a one-man reconnaissance vehicle capable of floating just above the ground at low altitude, but had not received any viable designs. The Avro craft looked promising.

Frost was still intent on making his design a supersonic fighter but the complex engine had proved almost impossible to complete. In the meantime, a scaled-down model was built for testing by the army.

It was out of this craft the Avrocar was born.

Amid internal turmoil at Avro and the eventual cancellation of the Avro Arrow on "Black Friday," Frost was forced to put his supersonic ambitions on hold. As it was, the low-altitude model was beset with power and control issues.

In videos, the Avrocar hovers about a metre above the ground. Reports suggest it never got above 3 metres and the brilliantly named test pilot Spud Potocki struggled to move the aircraft in any direction except forward without losing stability.

"A conventional aircraft is controlled by the tail fin and rudder and the stabilizers. The saucer had nothing, Frost's idea was to maintain control by manipulating vanes mounted around the periphery of the saucer ... the trouble was, the system didn't work," the Winnipeg Tribune reported in 1976.

Frustrated with the lack of progress, the U.S. military pulled out of the Avrocar project in 1960 and it was cancelled completely in 1961 without realizing its potential either as a supersonic fighter or a low-altitude, all-terrain vehicle.

Subsequent endeavours would eventually prove Frost's science sound. Modern hovercraft rely a similar method of lift, though many use a separate set of engines for forward thrust.

One of the two working Avrocar prototypes, still in its American livery, are on display at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum in Fort Eustis, Virginia.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Wikimedia Commons

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments