That time Nelson Mandela became a Toronto citizen

The first time Nelson Mandela stepped into the heat of a Toronto summer it was from the doors of a Canadair Cosmopolitan on the tarmac of Lester B. Pearson International Airport. It was June 19, 1990, and the anti-apartheid leader, released from prison only months earlier, had come to thank the people of Toronto for their support.

30,000 people packed University Ave. and Nathan Phillips Square to hear the 71-year-old leader of the African National Congress party, still fragile from 27 years of incarceration, address the city. Security was tight, as if for a royal visit, but this occasion had a different feel.

As Walter Stefaniuk wrote in the Toronto Star: "Mandela is a black man and a black or coloured person cannot lead an apartheid nation, or aspire to a state in life another human being may have as a political birthright."

He would become an honorary citizen of Toronto before he could legally be elected South Africa's first black president, but the barriers to his historic term of office were beginning to tumble.

Apartheid's racist laws permeated every part of life in South Africa in 1990. Blacks were not allowed to live in the same neighbourhood as whites, were not allowed to travel within the country without a passbook, and were not allowed to use beaches or park benches in the land of their birth, to name just a few of the countless restrictions.

Mandela had spent 27 years in an island prison, handed a life sentence for sabotage and conspiracy over his over his party's plans for a new model of government in South Africa, one not centred on division and hatred. He was released after years of mounting international pressure and trade boycotts on 11 Feb., 1990 before an international TV audience of millions.

In Toronto that summer, Mandela had been scheduled to speak at Nathan Phillips Square but was too tired from a hectic travel schedule. When he did address the public, it was from a stage on the front lawn of the Queen's Park legislature.

"We thank you for refusing to forget us," he said. "We thank you for your tireless support. It is remarkable that so many of you could give up so much of your time to help the people separated from you by thousands of miles. Thank you for that commitment and dedication. It reached all of us. We are on the threshold of major changes in South Africa."

His closing words were almost drowned out by chants of "Mandela, Mandela, Mandela." In Ottawa, he urged parliament and the people of Canada to "walk the last mile" with him on the road to democracy. Four years later he was elected president in the country's first ever multiracial vote.

When South Africa's outgoing president returned in September 1998 it was to collect an honorary companion of the Order of Canada, Canada's highest award. He had been South Africa's head of state for four years, leading the country out of apartheid and through a difficult process of healing.

"I humbly accept it as an expression of the deep bonds between the Canadian and South African peoples, based on our shared commitment to common values," he told a rapt audience at Rideau Hall in Ottawa. "I thank you from the bottom of my heart."

As newspapers reported, Mandela, 80, appeared physically frail. He wore hearing aids and was helped from the lectern by prime minister Jean ChrĂŠtien. Flash photography was prohibited due to problems with his eyesight but his distinctive voice was clear and unwavering.

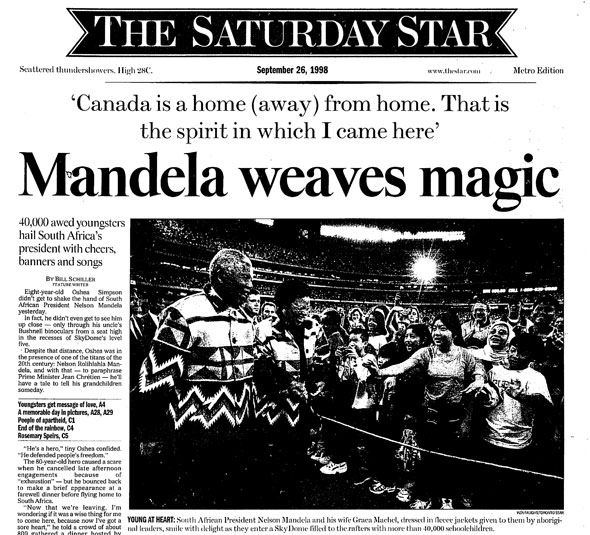

The official Canadian visit - his last in office - culminated in a packed mass rally at the SkyDome where Mandela was to announce the formation of the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund (Canada,) a local chapter of an international charity focused on children and youth.

40,000 eager students crowded the ball park to hear the international icon speak but likely few were as excited as 9-year-old Alon Meyer of Thornhill.

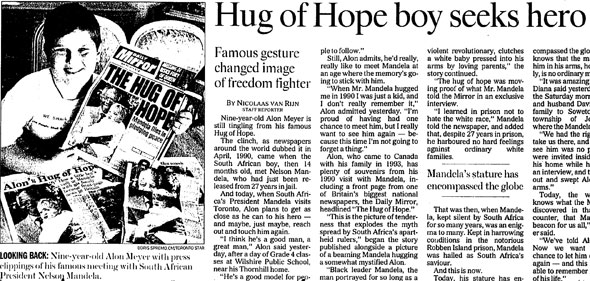

Born in South Africa, Alon was just a baby from an ordinary white family when he was suddenly thrust into the arms of newly released Nelson Mandela by his mother during a media event. The resulting photograph was carried in newspapers around the world and dubbed the "Hug of Hope."

"This is the picture of tenderness that explodes the myth spread by South Africa's apartheid rulers," wrote Britain's Daily Mirror. Alon was among the electric crowd at the SkyDome and said he planned to reach out and touch the man with whom he had shared an iconic photograph.

After Mandela's speech, in which he called Canada a "home from home," the first check for his new fund - $72.46 - awaited from the kids at Park Public School on Shuter Street, the oldest educational institution in Toronto still on its present site.

Mandela last visited Toronto in 2001, taking special time to repay the generosity of the Regent Park kids. In a visit to the school, he spoke powerfully of his affection for the students. "I love each and every one of you. Not as my child, not even as my grandchildren, but as our great grandchildren ... I love you from the bottom of my heart."

In return, Park Public School became Nelson Mandela Park Public School.

Ryerson celebrated the man known as "Tata" (Xhosa for "father") in his home nation, with an honorary degree, but there was one last gift from the people of Canada. In a simple ceremony at the Museum of Civilization on the banks of the Ottawa River, Jean ChrĂŠtien handed Mandela a certificate, the first of its kind issued to a living person.

South Africa's anti-apartheid leader, an icon and inspiration for millions, had become an honorary Canadian citizen.

"You have honoured me beyond anything I might have deserved," he said. "I thank you."

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments