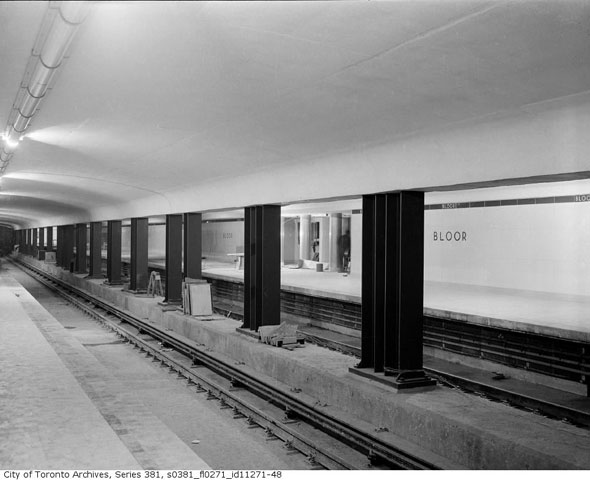

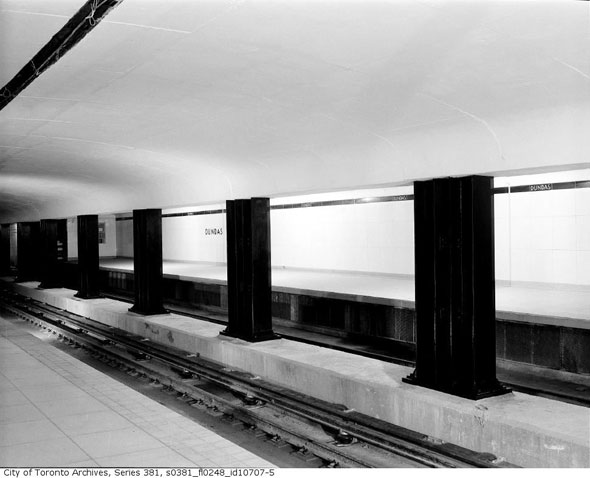

What the original TTC subway station tiles looked like

Long gone are the days when the Toronto subway had anything approaching a cohesive interior look. Though some efforts are being made to restore a handful of stations, the TTC has long allowed a hodgepodge of tile colours and textures to proliferate across the system.

It wasn't always so. When the Yonge line was still in the planning phase, the TTC selected a special kind of glass-faced ceramic tile to line the walls of the planned stations known as Vitrolite. The colours would alternate between stations but each would draw from the same theme, much like the Bloor-Danforth line (mostly) does.

Tenders SC-1 and SC-2, won by the Foundation Company of Canada, called for the glossy tile, popular in art deco buildings, over glazed terra-cotta and a type of tin-glazed tile, after the construction company offered a discount of $163,000. It still wasn't the cheapest option but the TTC board chose it anyway.

The original swatches consisted of four colours - "Primrose," "Pearl Grey," "Jade," and "Shell Pink" - but the supplier, Murray Associates, was ultimately unable to provide Shell Pink or Jade in the desired quantities at the budgeted price. "Alamo Tan" was offered as a substitute but the TTC settled on three tints for the 12 stations: "Primrose," "English Egg Shell," and "Pearl Grey."

Union station, shown below in its original tile, got Primrose, as did Dundas, Bloor, and St. Clair. Rosedale, at the top of the page, shared English Egg Shell with King, College, and Davisville while Eglinton, Summerhill, Wellesley, and Queen were lined in the Pearl Grey tone.

It's not completely clear what the TTC paid for the tile because the cost was often lumped in with other work the FCC carried out on the subway, including installing the cashier booths and building a station entrance at Union. One early breakdown put the cost at $1.6 million for materials and installation, though the price fluctuated once work began.

The tile itself, while attractive, was difficult to work with and had a tendency to shatter like glass. The FCC billed an extra $18,000 in broken tiles because it felt the problems were due to the "inherent character of the material," not the fault of its workmen.

The fragile nature of the Vitrolite glaze ultimately led to its gradual disappearance from the subway. Warping walls, shifting ground, or minor accidents would shatter entire two-inch thick tiles. Rather than pay for the upkeep, the TTC began replacing its original subway tile or covering it in plastic slats, in some cases entombing the damaged Vitrolite behind.

Lucky for us, photographer Ben Mark Holzberg documented the tile and donated his work to the national archives before much of it was lost for good. (Eglinton, pictured in close-up below, is the only station with its original glass-faced tile still intact.)

Some more colour pictures not included here, including a close-up of the tile at College, are available here.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Ben Mark Holzberg/Library and Archives Canada, City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments