5 lost rivers that run under Toronto

The Don, Humber, and Rouge get all the glory, but Toronto is much more than a three-river town. Before John Graves Simcoe, when the land that would occupy the city was thick with trees and thickets, its soft soil was traversed by numerous streams and creeks that over centuries etched out deep ravines and sculpted rolling dales.

As early city builders would find, it's actually quite difficult to completely erase a river, and many of the waterways that once penetrated downtown Toronto still exist, re-routed into culverts or sewers and (mostly) from view. Here are five buried rivers that used to flow through Toronto.

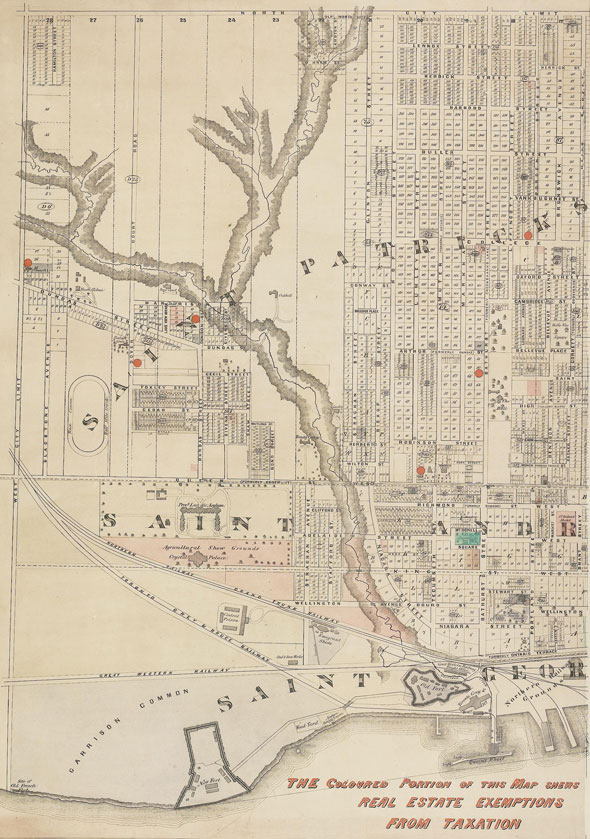

GARRISON CREEK

Of all the rivers present in early Toronto, Garrison Creek was the biggest and hardest to cross. Its winding course and ocasionally deep ravine proved a significant obstacle to the expanding city and substantial bridges were built at Dundas and Harbord streets, both of which have been buried but still stand.

Garrison Creek started north of St. Clair and headed directly south via Bloor and Christie under a half-buried bridge at Harbord - the stone wall on the north side of the street at Bickford Park is the bridge's parapet. It continued south, causing the weird dips and warped intersection on Crawford Street.

From there, Garrison Creek headed through Trinity Bellwoods Park, where there's another buried bridge under Crawford Street (the dog park is in part of the old ravine,) and out the southeast corner parallel to Niagara Street, where the river bank caused its distinctive arc. Garrison Creek drained into the Toronto Bay near Bathurst and Fort York Blvd.

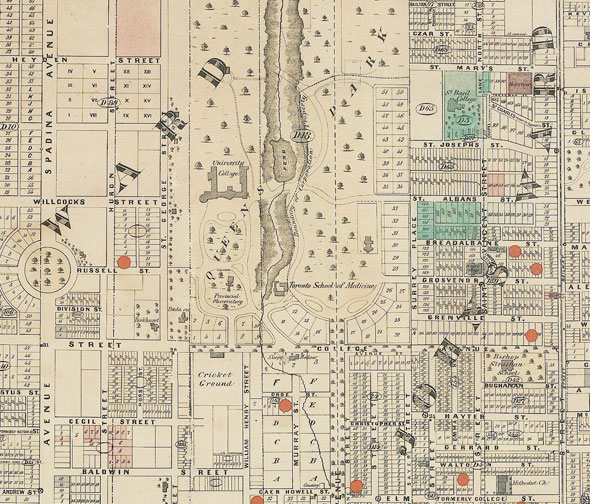

TADDLE CREEK

The geographical legacy of Taddle Creek, sometimes called Little Don River, is more subtle than that of its westerly cousin Garrison Creek. The odd dent in the southwest corner of Queen's Park Crescent and the gentle slope of Parliament just north of King are the extent of the river's surviving landscaping.

Possibly rising at Wychwood Park northwest of Davenport and Bathurst (no-one is entirely certain,) Taddle Creek flowed south along the eastern edge of the University of Toronto campus, forming a small pond at Hart House Circle that shows up early photos of the university grounds.

At College it swerved east, eventually draining into the bay near Parliament and Esplanade.

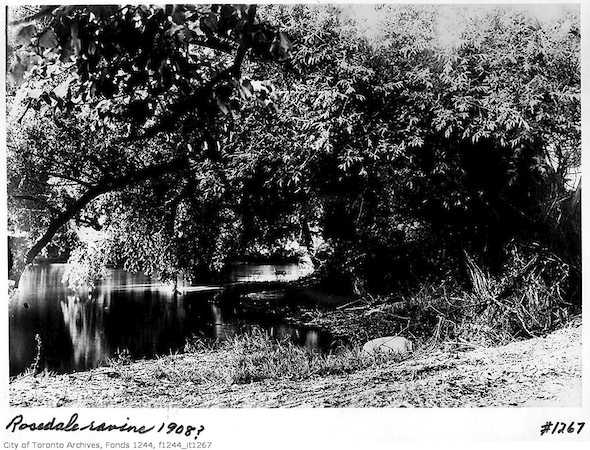

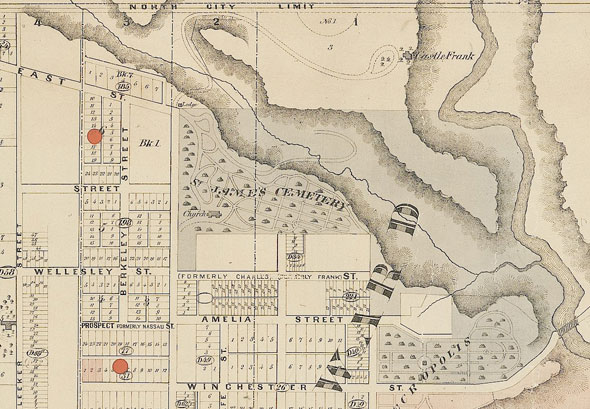

CASTLE FRANK BROOK

The steep sides of the Rosedale Ravine had to come from somewhere. Castle Frank Brook, the product of several smaller rivers that met near Cedarvale Park, eroded the Nordheimer Ravine, which could have carried the Spadina Expressway but now covers the Spadina line, and the deep Rosedale Ravine.

Today, Castle Frank Brook cuts under St. Clair West station, rises again in Sir Winston Churchill Park, and vanishes back into a sewer that carries it down under Rosedale Valley Road into the Don River opposite Riverdale Park.

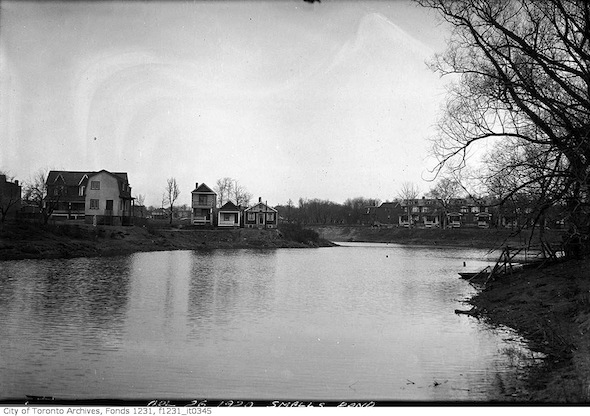

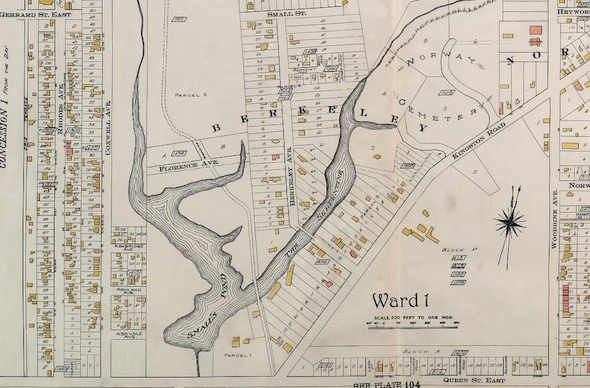

SMALL'S POND

The size of a small lake, Small's Pond once dominated the area close to Queen Street E and Kingston Road. It was fed by two separate streams, one that started near Gerrard and Coxwell, the other closer to Woodbine, and was once a prime source of beverage ice in the winter as many other bodies of water were considered too polluted.

The 12-metre deep, roughly U-shaped Small's Pond was naturally divided into two separate arms, one of which was popular with skaters and boaters and known locally as The Serpentine. The other, broader arm ran roughly parallel with Coxwell Ave.

In 1919, nine-year-old John Vice drowned in a weed-choked portion of the Small's Pond and the next year two small boys had to be pulled from its dark waters. Small's Pond became a stagnant, sewage-filled pool when its feeder streams were diverted into sewers. It was drained and filled in on health grounds around 1935. Orchard Park roughly marks the place where the two parts of Small's Pond met.

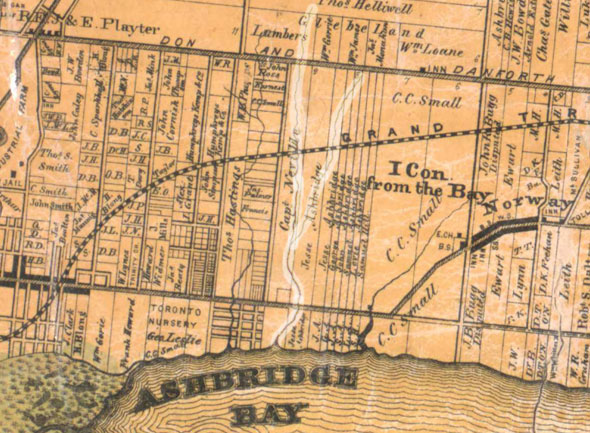

ASHBRIDGE'S CREEK

Ashbridge's Creek was so un-loved that it appears never to have been given an official name, though its geography is still easy to trace. Rising in two branches near today's Monarch Park, "the creek," as early landowners the Ashbridge family called it, passed under the rail tracks and down Woodfield Road, where it's still audible in the sewers.

At Gerrard, it moved slightly west, eroding a wide depression in the land where Highfield Road is now before draining into Lake Ontario at today's Eastern Avenue, just behind the streetcar yard. The lawn of the Ashbridge's home, which still stands on Queen Street E, got its dimpled texture from the river.

Today, Ashbridge's Creek flows into the Mid-Toronto Interceptor Sewer at Gerrard Street and ends life at the Ashbridges Bay Wastewater Treatment Plant.

For more information on lost rivers, visit Lost Rivers, a great little resource for everything wet and buried in Toronto. Nathan Ng's map site is a great resource for discovering old streams.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library,

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments