10 quirky things to know about the Don Valley

Toronto has a powerful love/hate relationship with the Don River. At once prized for its unspoilt scenery, the mighty river and its impressive valley have been extensively manhandled over the last 200 years, becoming at various times a source of disease, a toxic dump, and a convenient conduit for transportation.

Jennifer Bonnell is an assistant professor in the History Department at McMaster University. Her book, Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto's Don River Valley, traces the history of the waterway and explores our complex and evolving relationship with one of the city's most defining landscape features.

The book is full of fascinating insights into the history of the Don. With input from Bonnell, here are 10 strange but true facts about the Don and the Don Valley.

The Don River caught fire on at least two occasions

Two oil refineries--McColl-Frontenac and British American Oil--were located on the Don in the early 1900s, and product discharged from their factories that coated the surface of the river.

A fire destroyed a bridge across the river at Keating Street in 1931 and another in 1943 destroyed several properties. As a testament to the lack of environmental awareness, neither incident generated much press at the time, Bonnell writes.

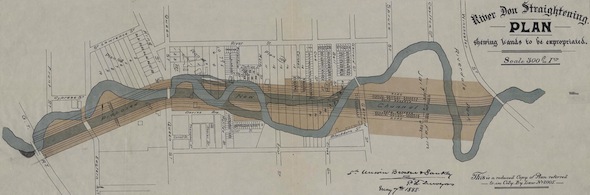

The lower portion of the Don was straightened, widened, and deepened

South of the Bloor Viaduct, the original course of the Don River has been erased. In the 1880s, the city planned and built new industrial hub along the banks of the river, in doing so freeing up space for a new eastern rail entrance to the city.

The original concept called for a straight run of the river through the Port Lands to better flush polluted water into the lake.

The right angled mouth of the river was built to avoid one of the oil refineries

The original mouth of the straightened Don River was supposed to connect to the lake via a gentle curve south of Eastern Avenue. Too bad that the British American Oil refinery lay in the way.

The company refused to budge, and in 1915, the mouth was made into a tight right angle at the Keating Channel to avoid the now-demolished property.

The Don Valley used to be a popular location for summer homes

The verdant scenery, abundant wildlife, and gentle sounds river sounds lured many people to build vacation cottages in the Don Valley, including noted naturalist Charles Sauriol, who had two homes knocked down, one in 1961 to make way for the Don Valley Parkway and another in 1968 due to conservation and flood damage mitigation efforts following Hurricane Hazel.

At one time, Sauriol had a large vegetable garden, orchard, and about 50 bee hives.

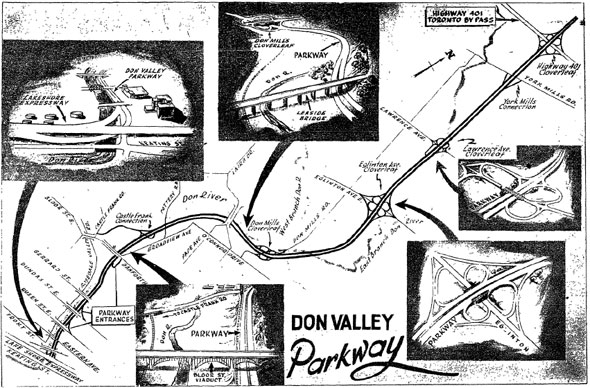

A proto-Don Valley Parkway was envisioned as early as 1914

With the straightening of the Don River, potential new transportation corridors were opened up on both sides of the water course.

The city eyed a potential low-speed parkway in 1943 that would have travelled in an n-shape up the Don Valley, over the top of the city, and down the Humber River Valley, but the idea was shelved. It would take until the 1950s for the DVP to become a reality.

Squatters also holed up in shacks and caves in the Don Valley

As early as the 1820s the Don Valley has sustained a population of homeless people. "One of the first recorded squatters in the valley was Joseph Tyler, who, according to 19th century Toronto historian Henry Scadding, lived in a cave on the side of a hill in the valley near the Queen Street bridge," Bonnell writes.

Tyler was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War and made a little money selling building materials or ferrying beer in a canoe from the Helliwell Brewery at Todmorden to the city.

The Port Lands was once one of the largest marshes on Lake Ontario

Industrialization might have made the city rich, but it entirely wiped out one of the great marsh areas of Lake Ontario. Early maps show the mouth of the Don covered in reeds, ponds, and little creeks that provided homes for migratory birds and other wildlife.

The marsh once extended as far east as Leslie Street and served as a permanent connection to the Toronto Islands. A storm 1858 permanently severed the connection to the mainland.

The steep sides of the Don Valley used to be popular with skiiers

In 1934, the Don Valley was home to an insane 30-metre ski jump. Built by the Toronto Ski Club near Thorncliffe for a competition, the wooden ramp promised to launch participants some 50 metres into the valley.

The winning participant, 17-year-old Teddie Zinkin, managed 34 metres on the day in front of thousands of spectators. Later, the wall of the valley just south of Lawrence was a city-owned ski hill. Today, a single pylon from the lift is all that remains.

The Don Valley used to be a hotbed of malaria

When early Toronto settlers complained of fever and chills, they called it "ague" or "lake fever," but what really ailed them was malaria. The disease-carrying mosquitos once reached as far north as Southern Ontario, taking advantage of pooled water and land disturbed by construction.

The area around the mouth of the Don was one of the worst affected areas in the city.

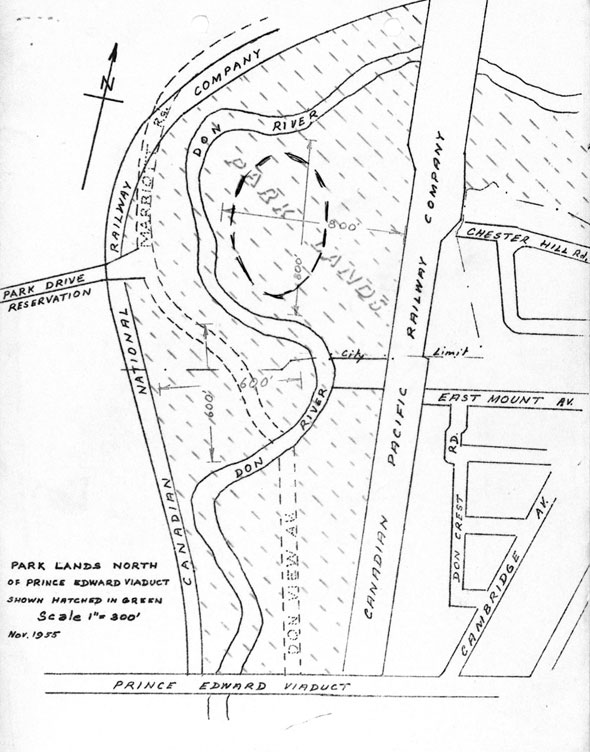

The city once eyed part of the valley floor as a possible baseball stadium location

Before the city got the Blue Jays expansion franchise in the late 1970s, the city actively sought a Major League Baseball team in 1960. Tentatively known as the Toronto Canadians, the city offered up several possible locations, two of them in the Don Valley.

One in Riverdale Park and another north of the Bloor Street Viaduct. The latter, which was sketched opposite the Chester Hill Lookout, would have nestled in the crook of the river. Escalators and elevators would have connected the stadium with Broadview subway station.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments