10 quirky things to know about Etobicoke

Modern day Etobicoke, like the City of Toronto, is a relatively recent construction. Once a disparate collection of small towns and villages, the current city is a suburban spread of high-rise apartments, leafy residential streets, and tough-looking industrial zones.

Toronto's western neighbourhoods are also home to numerous tantalizing curiosities, including remnants of a lost village absorbed and almost erased by the encroachment of modern industry, a massive and ornate Hindu temple, a pioneer cemetery landlocked by highway ramps, and a tiny fragment of a cancelled light rail line at Kipling station.

Here are 10 quirky things to know about Etobicoke.

The name "Etobicoke" is a reference to trees

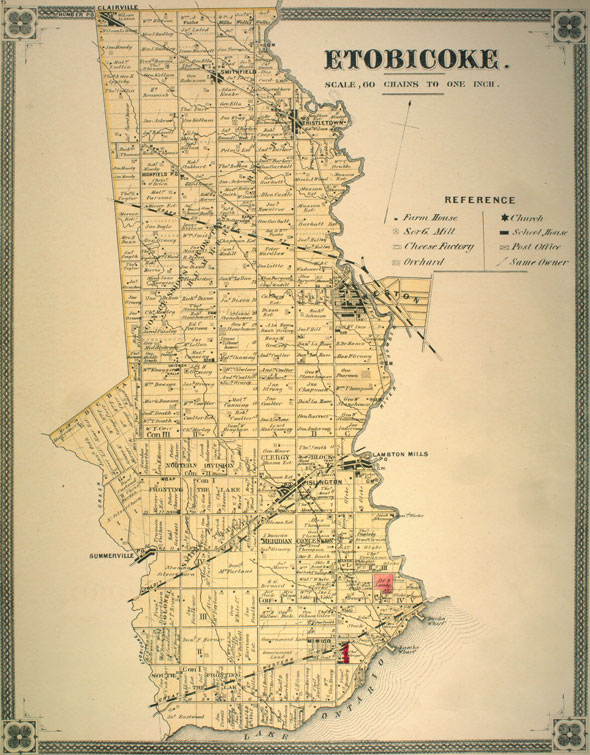

The Etobicoke name with its bizarre silent "k" is derived from the Ojibwe word "wadoopikaang," which is used to refer to a place where alder trees grow. Over time, the word was gradually corrupted and anglicized into "atobecoake" and finally "Etobicoke."

The land was part of the controversial Toronto Purchase of 1787, a deal that transferred control of a large swath of Toronto land from First Nations people in exchange for 2,000 gun flints, 24 brass kettles, 120 mirrors, 24 laced hats, 96 gallons of rum, and a bolt of floral flannel.

The land was part of the controversial Toronto Purchase of 1787, a deal that transferred control of a large swath of Toronto land from First Nations people in exchange for 2,000 gun flints, 24 brass kettles, 120 mirrors, 24 laced hats, 96 gallons of rum, and a bolt of floral flannel.

Long Branch used to be a summer resort

In the days when the intersection of Brown's Line and Lake Shore Blvd. was a rural oasis, entrepreneur Thomas Wilkie bought and subdivided a portion of prime lakefront property into 219 cottage-sized lots, just southeast of where the 501 Queen streetcar ends today.

The new neighbourhood included a park (called, imaginatively, Sea Breeze,) a luxury hotel, and numerous spectacular mansions. Before the streetcar, access was via rail or steamer from the foot of Yonge St. Several of the old summer homes still remain.

Hurricane Hazel killed 35 people on one Etobicoke street

When Hurricane Hazel ripped through Toronto in 1954, the area around the Humber River was hit particularly hard. The river swelled to several times its normal size and burst its banks, washing out bridges and dragging away homes.

On Raymore Drive, which was located inside the river valley just south of Lawrence, 35 people were killed when the water washed away their homes. The location of the disaster, which was responsible for almost half of Hazel's deaths in Ontario, is now Raymore Park.

There were once plans to build light rail out of Kipling station

Transit plans change as frequently the seasons in Toronto, so it's perhaps no surprise that Kipling station harbours evidence of a dead light rail transit line. The route, planned in the early 1980s, would have run north along the Kipling hydro corridor to Pearson airport, then east to York University.

Had it been built, the light rail line would probably have used articulated streetcars, possibly tethered together. The roughed in platform opposite the bus bays was the only piece ever built.

There's a hidden pioneer cemetery in the Highway 427/401 interchange

Richview Memorial Cemetery doesn't really do the whole "rest in peace" thing. Bound on two sides by highway and on another by Eglinton Ave., the resting place, which dates back to 1846, is never dark or quiet.

Amazingly, despite the oppressive surroundings, burials still take place at Richview in full view of speeding trucks and cars. About 300 people are currently working their way through eternity there.

The Bloor-Danforth line could have reached Sherway Gardens or Mississauga

The Bloor-Danforth line has been extended twice since it opened in 1966--from the original terminus at Keele to Islington in 1968, and from Islington to Kipling in 1980.

A plan to push the line west into Mississauga via Sherway Gardens was floated at various times during the 1980s and 1990s, but was repeatedly shelved over the projected costs and a predicted lack of ridership. Had it been built, there would likely have been stops at East Mall, West Mall, and Dixie.

Northwest Etobicoke has its own ghost town

Before Claireville effectively became an industrial park, it was a small village on the outskirts of Toronto. As Sean Marshall wrote for Spacing, at its peak, the little community had several churches, some small businesses, and a smattering of homes, a small number of which survive.

The area was rezoned as the city grew and all but a few pieces of the town were demolished. Just south of the old village lies a disused portion of Indian Line that runs parallel to Highway 427.

A gorgeous Hindu temple is hidden on industrial Claireville Drive

Completed in 2007, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Etobicoke's extreme northwest corner is made of 24,151 handcarved pieces of marble and stone.

There's no central steel structure or central supporting skeleton - the entire building, all 10,000 tons of Italian marble, Turkish limestone, Indian sandstone, and granite, is self-supporting.

The first Toronto piece of the 401 was built in Etobicoke

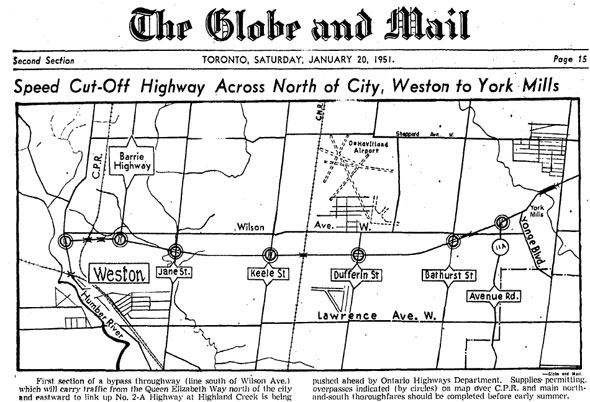

Highway 401 was originally conceived as a high-speed Toronto bypass. Drivers travelling on Highway 2, snarled by traffic lights and heavy traffic, would be able to cruise over the top of Toronto en route to Windsor or Quebec.

The first Toronto section was built from the Humber River to Avenue Rd. in 1951. The four-lane highway was the first in the city to feature cloverleaf interchanges and the now-familiar highway-style access roads.

Unfortunately, the highway was never a driver's dream. By 1956, the traffic was already "intolerable," according to the Globe and Mail.

The oldest home in Etobicoke dates between 1802 and 1820

Located on a street overlooking the Humber River and nuzzled up against new suburban-style property, Etobicoke's oldest surviving home predates the name of the Thistletown neighbourhood to which it belongs.

John Grubb, a businessman responsible for the construction of Albion Rd., built the stone cottage on Jason Rd. between 1802 and 1820. The area was predominantly rural until the spread of the suburbs in the 1950s and 60s.

Jack Landau, o.mutukuda, Marika van Velsen/blogTO Flickr pool, City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments