10 strange and unusual things you might not know about the Toronto Islands

The Toronto Islands have a deep and rich history that affirms there's no place quite like it.

Over the last 200 years, the sandy strip of land has evolved from a pond and wildflower-covered peninsula, to a summer playground paradise complete with rides, beaches and other amusements.

Over its history, the natural landscape of the islands and its waterways have been extensively altered. It's doubtful anyone who rode the wooden roller coaster at Hanlan's Point way back in the day would recognize the topography of the Toronto Islands today.

Here are some quirky things to know about the Toronto Islands.

The Islands used to have a name

Toronto is full of painfully unimaginative names. Where is The Ex held? Exhibition Place. What should we call the new square at Yonge and Dundas? Yonge-Dundas Square.

The Toronto Islands fall into that same category, but for a while the area had a semi-official name: Island of Hiawatha, after an early First Nations leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy.

The name appeared on maps as late as 1924 as a collective name for all the Toronto Islands.

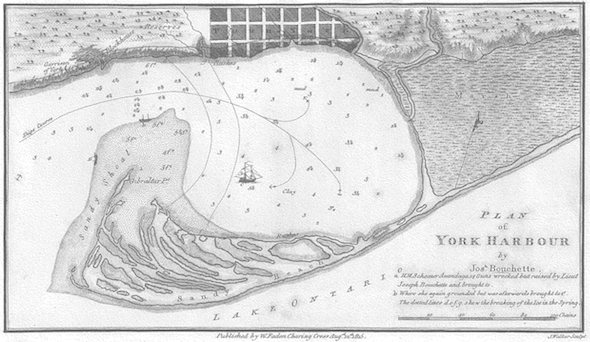

The Islands used to be a peninsula

The Toronto Islands were, until a particularly strong storm in 1858, linked to the mainland.

Before the marshy mouth of the Don River was turned into the Port Lands, a nine km spit of eroded Scarborough Bluff sand stretched from the foot of Leslie Street to roughly Bathurst Street, forming a "narrow neck of ground," in the words of Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of York founder John Graves Simcoe.

The sand bar, which is now the Islands, was covered in small ponds, wild flowers, vines, fir and poplar trees. It was also an important ground for First Nations hunters and fishers.

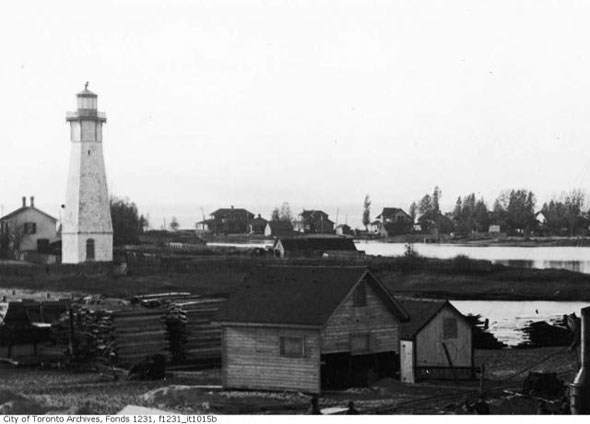

The first lighthouse keeper was murdered

Poor unfortunate John Paul Radelmüller has had a rough ride. Lazily accused by some historians of being mixed up with bootleggers and crooks before his murder in 1815, it seems the unfortunate German-born lighthouse keeper likely met his end as the victim of a robbery.

As writer Sarah B. Hood wrote in the winter 2012 issue of Spacing, Radelmüller was responsible for collecting import duties and he may have been killed for the tax revenue in his possession.

No one was ever convicted of the crime and over the centuries the death has been embellished to include ghouls and bloody staircases.

The Islands used to be a popular location for mansions

The boardwalk on the lake side of Centre Island roughly follows the path of Lake Shore Avenue, a lost road that used to be Toronto's mansion row.

The city's richest people — investment banker Arthur Massey, city engineer Charles Rust, and Gooderham and Worts president Gordon Gooderham — built large summer homes along the street that afforded expansive views of the lake.

The church of St. Andrew by-the-Lake, built in 1884, is a conspicuous relic of this time.

Babe Ruth hit his first professional home run at Hanlan's Point

In 1914, before he was the Bambino or the Sultan of Swat, George Herman Ruth was a minor leaguer with the Providence Grays. During a game at the 18,000-capacity Hanlan's Point Stadium against the Toronto Maple Leafs, Ruth belted one into right field, the first of many home runs in his professional career.

No-one is sure where the ball went. It could have dropped into the water, been collected by a fan, or simply thrown back onto the field. Either way, the Holy Grail of baseball is long gone now.

The Islands could have had a manmade neighbour

Harbour City was one of the most ambitious unbuilt projects in Toronto. The chain of manmade islands were supposed to include offshore housing for some 60,000 people, a network of artificial lagoons and canals for recreation and transportation, and commercial properties.

Part of the development would be in the lake opposite Exhibition Place, the rest on what would become former airport land (see below.) Harbour City died with the Spadina Expressway project in the early 1970s.

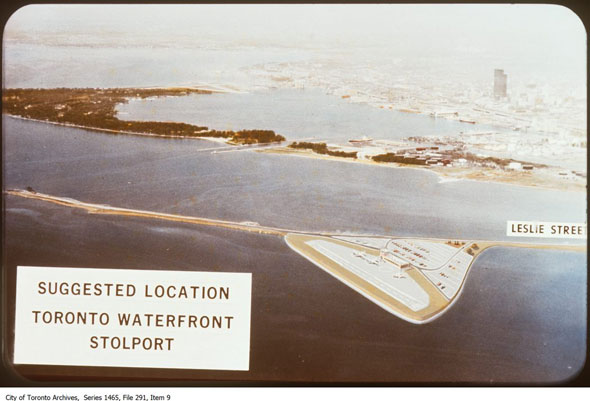

The Island airport could have been in the Port Lands

STOLports were all the rage in the 1960s. Short for "short take-off and landing," the miniature air strips were designed for special city-hopping aircrafts that were able to use extremely short runways. The Toronto STOLport was supposed to have been built on the tip of the Leslie St. Spit.

From there, the planes — De Havilland DHC-7s — could reach cities up to 800 km away, including New York, Chicago, Quebec, and Louisville. The plans fizzled, but eventually led to the expansion of the existing Island airport into its current size.

There used to be a lot more people living on the Islands

Today, there are about 260 homes on the Toronto Islands, but until the 1950s, there were as many as 8,000 people living offshore.

The decline is the result of a lengthy legal dispute between the various owners of the Islands, who would rather the area become parkland, and the existing residents.

The feud was most recently settled in 1982 with a decision that allowed existing islanders to lease land from the city until 2092.

Hanlan's Point used to be Toronto's Coney Island

While the eastern portion of Centre Island was an area popular with the city's highest earners, Hanlan's Point was Toronto's working class playground.

An amusement park with a massive wooden roller coaster, miniature railway, whiplash-inducing "whip," circular roller rink, and baseball stadium drew massive crowds until the late 1920s, when the park fell into decline amid competition from Sunnyside and financial pressure brought about by the Great Depression.

It closed for good in 1930s and was replaced by the Island Airport.

The airport ferry is one of the shortest in the world

The Island airport ferry is ridiculous. At 121 metres, the gap between the mainland and the terminal is so short that the Port Authority could technically park a longer vessel in the gap and have people walk on the front and step off the back.

For complex political reasons, the city was unable to build a fixed vehicle or pedestrian link to the Island until the opening of the pedestrian tunnel in 2015.

A Great Capture. Additional images courtesy City of Toronto Archives.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments