The history behind the construction of Highway 401 in Toronto

When work began on what would become Highway 401 in 1946, nobody imagined what a monster it would become.

The Toronto portion of the road, built as a four-lane, limited access express route between what is now Highway 427 and the Rouge River was supposed to be a high-speed bypass for through motorists.

Drivers snarled by traffic lights and stop signs on old Highway 2 would be free to cruise uninterrupted over the north of the city, the province promised.

"Provincial highway bypasses may end to traffic tie-ups," The Globe and Mail suggested in an August 1952 headline. Too bad it didn't work out like that.

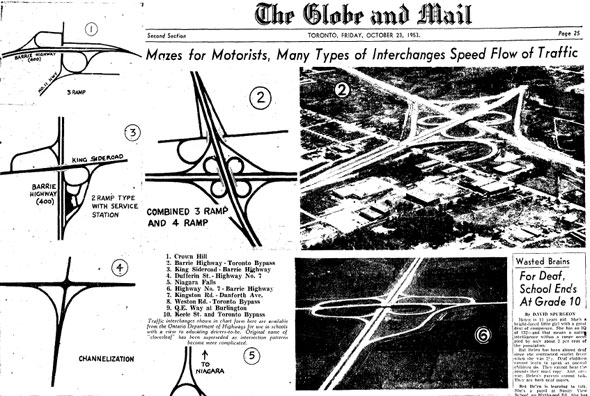

An article about the 401 in The Globe and Mail.

The origins for today's 401 can be traced back to the first piece of the Queen Elizabeth Way. Opened in the 1930s, the four-lane highway with its grassy median was the first of its kind in North America between two towns.

The design, championed by provincial minister of highways Thomas McQuesten, was based on the German autobahn and it gave drivers in Ontario their first taste of freeway driving.

Unlike the QEW, the 401 was designed during the second world war to bypass the towns and cities of the GTA, rather than link them.

Planners secured a wide right-of-way to permit future expansion in an arc over the north of Toronto: up today's 427, east-west parallel to Wilson Ave., then over to the Rouge River where Highway 2 and the 401 intersect today. The project was known as the Toronto Bypass.

Instead of laying down the blacktop all in one go, the highway was stitched together in pieces, starting with the Highland Creek to Oshawa portion east of Toronto in 1946.

Post-war shortages and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 delayed construction of the remaining portions by several years.

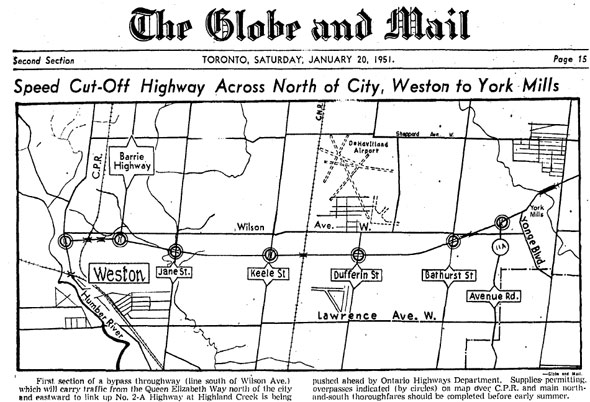

An article in The Globe and Mail.

In January 1951, work had begun on the western portion of the Toronto Bypass from Weston to York Mills.

"Slashing like a fawn ribbon across the fields and through the thinly populated areas north of Toronto, the projected four-lane cutoff designed to connect the new Barrie highway with Yonge St., Avenue Rd., and other north-south thoroughfares is progressing steadily through early stages of basic construction," The Globe and Mail wrote.

There were fears a shortage of structural steel for bridges and rail overpasses could delay the project, but there was also a sense of urgency among provincial officials who feared Toronto would fall behind other cities if it didn't build highways.

"We must not hamper our growth by failing to develop highway transportation," said highways minister George Doucette, who was ironically hospitalized at the time following a motor crash.

Construction of the 401.

Like Toronto's first subway, which was soon to be built under Yonge St. between Union and Eglinton, designers strived for a clean, uncluttered look for the bypass.

"Unlike U. S. freeways, part of the 401 plan was to build a freeway with bridges and interchanges that displayed clean lines, dramatic simplicity and an impression of airiness," writes highway historian John Shragge.

"The concept also included a ban on commercial billboards, tourist signs and construction of buildings within a quarter of a mile of the freeway to avoid clutter."

The Toronto Bypass didn't acquire its numerical name until 1952. (The "Macdonald-Cartier" designation didn't arrive until January 1965, the 150th birthday of Sir John A. Macdonald.)

By 1953, work had begun on the eastern portion of the Toronto Bypass, from York Mills to Sheppard in Scarborough.

On this section alone there were 11 cloverleafs, which were at the time a confusing novelty to Toronto motorists. In an attempt to prevent potentially dangerous situations, the Ontario Ministry of Highways printed special charts for use in driving schools.

Highway 401 before the construction.

One of the stranger ideas that surfaced during construction was a plan to plant trees and rose bushes along the highway shoulder. The Ministry of Highways believed planting flowers--turning the road into "a thing of beauty to behold"--would encourage drivers to slow down, while the trees would act as snow fences.

The idea came about after the province committed to replace every tree cut down during building work. 326,465 trees and shrubs were planted in 1954 alone.

Early Ontario highway drivers were restricted to one of three speed limits. Depending on the section of the road, the speed limit was either 60 mph (96 km/h,) 55 mph (86 km/h,) or 50 mph (80 km/h.)

The varying speeds were eventually standardized to 80 km/h until 1968, when it was briefly raised to 112 km/h. The limit has been 100 km/h since 1976.

The anticipated shortage of structural steel became a reality in 1955. A lack of materials delayed completion of the bridge over the Don River, but there had been bigger problems the year before.

The new highway bridge over the Humber River was washed out by Hurricane Hazel and had to be extensively rebuilt. Archival photos show tonnes of river silt over the surface of the road and deep cracks in the structure.

Construction of the 401.

The Toronto Bypass, two lanes in either direction from Islington to Markham Rd., opened in 1956. The 37 km stretch cost about $17 million (close to $150 million in today's money) but never became a paradise for motorists.

No sooner had the ribbon been cut were plans in the works for expansion. Four lanes became six, then 12, before the familiar express and collector configuration was added in an attempt to make the road flow better.

Unfortunately for drivers, the 401 never became a motorists paradise. An editorial in The Globe and Mail said the project had been "bungled." It said the road was too narrow and had too many interchanges that invited "short-trip local drivers to clutter up the road."

The volume of cars was already "intolerable," the paper wrote.

The full highway was completed from Windsor to the Quebec border in 1968. It's been growing in size ever since. Through Toronto, the express and collector layout swells the road to in excess of 12 lanes, making the road one of the largest and busiest in the world.

Good thing the planners left room to expand.

Archives of Ontario. Additional photos: Globe and Mail, Jan. 20, 1951, Apr. 17, 1953, and Oct. 23, 1953; City of Toronto Archives; Toronto Public Library, S 1-2080A.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments