A brief history of post-war feminism in Toronto

In honour of International Women's Day, last week I wrote about the rise of first wave feminism in Toronto, with a focus on the work of Anglo-Canadian women and their efforts to both improve society, and, crucially, to secure the right to vote.

Today's article sketches out what Indigenous and African-Canadian women were doing in the mid-twentieth century to improve the lives of women as well as their greater communities. I'll also take a brief look at what women were doing in Toronto as part of the second wave of feminism (chronologically speaking, up until around the 1980s).

African Canadian Women's Activism

African-Canadian women were generally excluded from the women's organizations of the first wave, but by the post-war period, they were forming their own organizations to fight for their own goals. Well-known Canadian author Lawrence Hill's history of the Canadian Negro Women's Association tells the story of how the African-Canadian women's organization was founded in Toronto in 1951 by Kay Livingstone, with an initial focus on providing scholarship for African-Canadian children to encourage them to stay in school.

Two decades later, Livingstone's vision of organizing Black women across Canada began to fall into place, with the first meeting of the National Congress of Black Women, held in Toronto in 1973. Over two hundred women attended the weekend-long event at the Westbury Hotel (475 Yonge Street, now the Courtyard Marriott.

The Toronto Chapter of the CBW was founded that year as well by the Honourable Jean Augustine, a teacher and social activist within the Caribbean community on Toronto (see photo above). This was the first meeting of Black women from across Canada who came together to discuss issues that affected them all. The Congress had several goals, including fostering solidarity amongst Black women, pushing for education programs, and making contact with other organizations who worked for similar purposes.

In 1979, Toronto became the first municipality to proclaim Black History Month, and in 1995, Augustine, then a Toronto MP, introduced a motion in the House of Commons to recognize Black History month across Canada. Today, the Congress of Black Women of Canada continues in its efforts, with multiple chapters in Ontario, including several in Toronto.

Indigenous Women's Activism

Indigenous women were also active through these decades, working to promote the rights of Indigenous women. However, their efforts were less centralized in Toronto. Heather Howard-Bobiwash has written about how Indigenous women who came to Toronto in the post-war era for work and education founded the North American Indian Club, which later became the Native Canadian Centre along with the Native Centre's Ladies' Auxiliary, who did much of the organizing and necessary fundraising.

The organization offered programs and services to help Indigenous men and women in the city, but also served as a hub of Indigenous activism. They started meeting at the YMCA at Yonge and College in the 1950s, and later moved to a rented space at 603 Church Street in 1962 When they outgrew that space, they moved to 210 Beverley Street in 1966, before moving to their present location at 16 Spadina Road.

One of the major concerns for Indigenous women was the discriminatory nature of the Indian Act which said that Indigenous women who "married out," or married a non-Indigenous man, lost their Indian status, and rights to live on her reserve, participate and band politics, or qualify for education or health benefits.

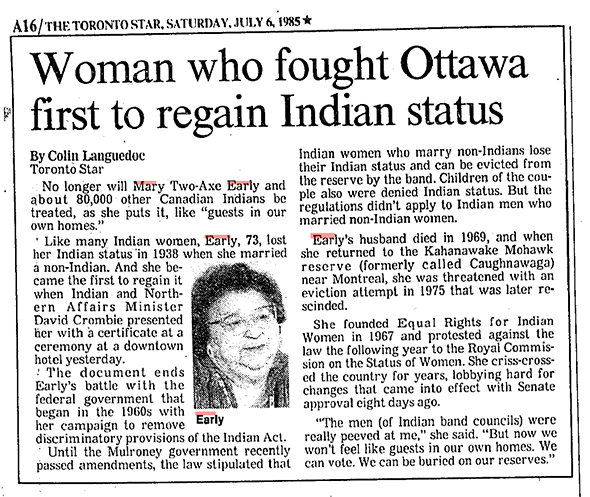

Several activists worked to make changes to the Indian Act throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, including Mary Two-Axe Early, a Mohawk women from Kahnawake, Quebec, and Sandra Lovelace, from Tobique, New Brunswick. Early founded the organization Equal Rights for Indian Women. Activists wrote letters, met with politicians, gave lectures and talks on the subject of Indigenous women's rights, and argued for giving women and their dependents back their status.

After filing complaints with the UN Human Rights Commission, and staging the Native Women's Walk to Ottawa in 1979, they started to make some important political breakthroughs. But it wasn't until 1985 that the Parliament of Canada passed Bill C-31, the bill to eliminate sexual discrimination in the Indian Act.

It restored status to tends of thousands of Indigenous women and their children and grand children. Mary Two-Axe early became the first women in Canada to regain her Indian status at a ceremony in Toronto. She was presented with written confirmation by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, David Crombie, who served as Toronto's mayor throughout the 1970s.

Crombie said to her "I could find no greater tribute to your long years of work than to let history record that you are the first person to have their rights restored under the new legislation." Early responded: "Now I'll have legal rights again. After all these years, I'll be legally entitled to live on the reserve, to own property, die and be buried with my own people."

The Native Women's Association of Canada was founded in 1973, the same year as the National Congress of Black Women. They organized as an umbrella organization, united thirteen groups from across Canada who had similar goals of achieving equal rights of Indigenous women, reshaping legislation on Indigenous women, and preserving and promoting Indigenous culture.

The group is very active today, and is using several strategies to prevent and address violence against Indigenous women and girls. They are lobbying for an inquiry into the 1,200 + missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada, holding vigils, and conducting research into the inequality that Indigenous women face.

The Second Wave of Feminism in Toronto

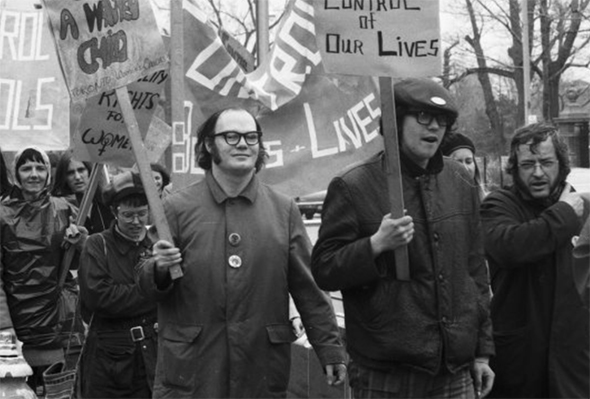

The second wave, which began in the decades after World War II, and continued until the late 1980s, was generally focused on four areas: women's reproductive rights, women's role in the workforce, equal pay for equal work, and violence against women.

As with the first wave, Toronto was the location of many protests, headquarters for numerous important organizations, and meetings. But of course, many protests took place in Ottawa, and women' organizations were located across the country.

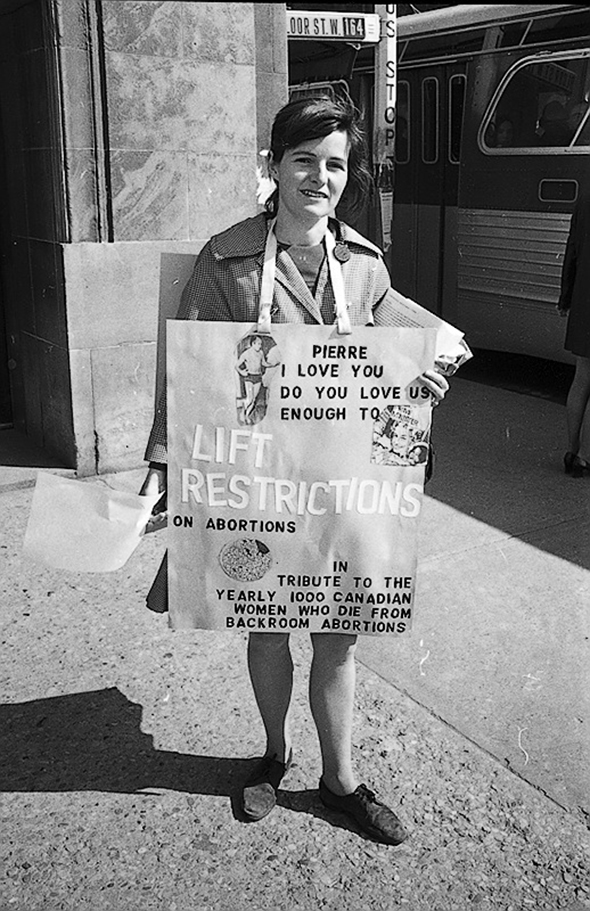

Abortion has been (and still is) a major issue for feminists who have fought for the right to abortion, and access to it. In Canada, the struggle began in the late 1960s, and in part, centred around Dr. Henry Morgentaler's clinic in Montreal. In 1983, Morgentaler opened clinics in Winnipeg and Toronto, even though abortion was still illegal under the Criminal Code. The Toronto Clinic was located at 85 Harbord St. above the Toronto Women's Bookstore.

Police raided both clinics, and the following year, he was charged with "conspiring to procure a miscarriage" at the Toronto clinic. He was acquitted, but the Ontario government appealed and a new trial was ordered. Finally, in 1988, the Supreme Court struck down the abortion law as unconstitutional. Despite it's legality, activists continued to have to fight for access . The original clinic, was firebombed in 1992.

The Toronto Women's Bookstore, an important home of feminist and women's publications, was destroyed as a result of the fire, and moved to 73 Harbord in June 1984, a space which they occupied until it closed in 2012. Throughout the 1980s and beyond, pro-choice women continued to protest threats to access to abortion services in this city. [add in pdf of article (or just photo from) Globe pro-choice article)

Today, the Morgentaler Cinic still exists on Hillsdale Ave near Bayview and Eglinton. Morgentaler himself passed away in 2013 after receiving the Order of Canada in 2008.

The third wave of feminism in Canada began in the 1990s, and has focused much more on anti-racism, anti-colonialism and anti-capitalism. While women in the second-wave often talked about "sisterhood," they were generally focused on women's issues in general, and weren't so thoughtful about how race affected their "sisters" in the city, or in Canada.

Third wave feminists have argued that feminists can discriminate against each other, and do so when they focus on the universalism of women's experiences, rather than on the diversity of women's experiences. The third wave involves many more grassroots organizations, rather than the nationalist centralized organizations that characterized both the first and second waves. And Toronto has been, and continues to be an important location for such organizing.

Images: New feminists abortion caravan, May 7, 1970. Photographer: Jac Holland. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC04612; Toronto Archives; Abortion laws: protest: picketers at subway station, April 22, 1970. Photographer: Jim Kennedy. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC06160; Womens liberation : free abortion on demand demonstration, May 10, 1971. Photographer: John Sharp. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC04911.

Alison Norman is a historian who lives in Toronto. She teaches in Canadian and Indigenous Studies at Trent University. Follow her on Twitter at @alisonenorman

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments