The history of schools in Toronto and their connection to Egerton Ryerson

While various forms of schooling were available in the area we now call Toronto from its earliest days as colony, the history of the city's public school system as we know it today can be traced back to 1847.

That was the year that the Toronto Normal School opened. It was the first teachers' college not just in the recently incorporated city but in all of Upper Canada, which eventually gave its location at St. James Square the nickname "the cradle of Ontario's education system."

Jarvis Collegiate, Toronto's oldest public secondary school pre-dates the Normal School by 40 years, but the vast majority of schools that remain in the city today derive from the period following formation of a central teaching facility.

The Normal School in 1856.

The Normal School bounced between a few locations in its first years, but in 1852 it found a home on Gould St. in a Classical Revival style building designed by architects. F. W. Cumberland and Thomas Ridout. The campus was eight acres, and offered a view down to the lake.

The force behind the foundation of the Normal School was the controversial racist and sexist Egerton Ryerson, whose name will finally be removed from the university that's located on the same grounds. While the building was demolished in 1963, portions of its facade remain.

Ryerson became the Chief Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada in 1844. Shortly after, he wrote the highly influential "Report on a System of Public Elementary Education for Upper Canada," which established the need for a teachers' college.

The Normal School was much more than just a teaching academy, though.

Ryerson envisioned it as an artistic and cultural hub that would serve as the cornerstone for educational resources in the province, and it's remarkable to think of how many cultural institutions have their origins here.

The Normal School in the early 20th century.

Founded in 1857 at the Normal School, the Museum of Natural History and Fine Arts would eventually become the ROM. The Ontario Society of Artists (1872) would become what is now known as OCADU. And the Ontario Agricultural College (1874) would eventually give rise to the University of Guelph.

In addition to breeding these institutions, the Normal School also helped to modernize Toronto's public school system, as did legislation passed by Egerton Ryerson in 1850 that paved the way for municipally elected school boards.

While there's some debate regarding the founding date for the Toronto Board of Education, 1850 tends to be the default as it corresponds with the passing of this legislation in Upper Canada.

Jarvis Collegiate in 1926.

There are numerous schools that pre-date this period, including Jarvis Collegiate (1807), Jesse Ketchum Public School (1831), and the Ward School/Enoch Turner (1849), but the major expansion of Toronto's public school system would come in the decades that followed.

Toronto's Catholic School Board, it should be noted, can also be traced to this time.

Separate school legislation was passed in 1841 thanks to the relationship between Canada East (Quebec) and Canada West (Ontario). St. Paul's Catholic School opened that same year. A second school, St. Mary's, followed in 1847.

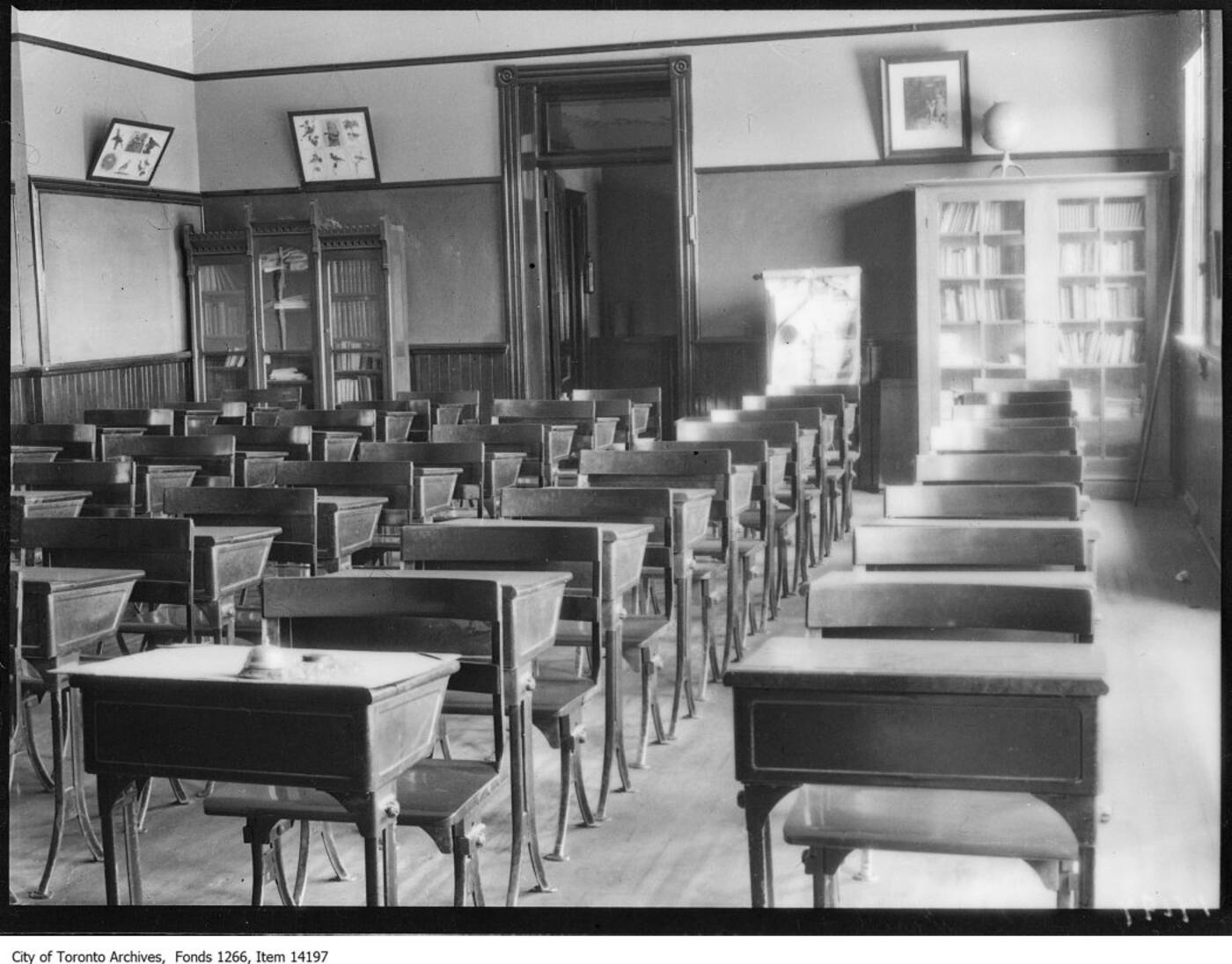

Interior of classroom at Swansea Public School.

By the end of the 19th century, a host of large-scale schools had opened under the Toronto Board of Education. Weston (1857), Harbord (1892), Humberside (18992, and Parkdale Collegiate (1888) all date back to this period. Ditto for primary schools like John Fisher (1887) and Swansea (1890).

It wasn't until 1904 that Toronto's elementary and high schools were linked, which took place during a period of great expansion for the Board of Education. The city was growing fast, and it needed a robust school system.

Central Technical School in 1919.

Many of the city's imposing schools built in the Collegiate Gothic style of architecture like Central Tech (1915) and Northern Secondary (1930) derive from this period.

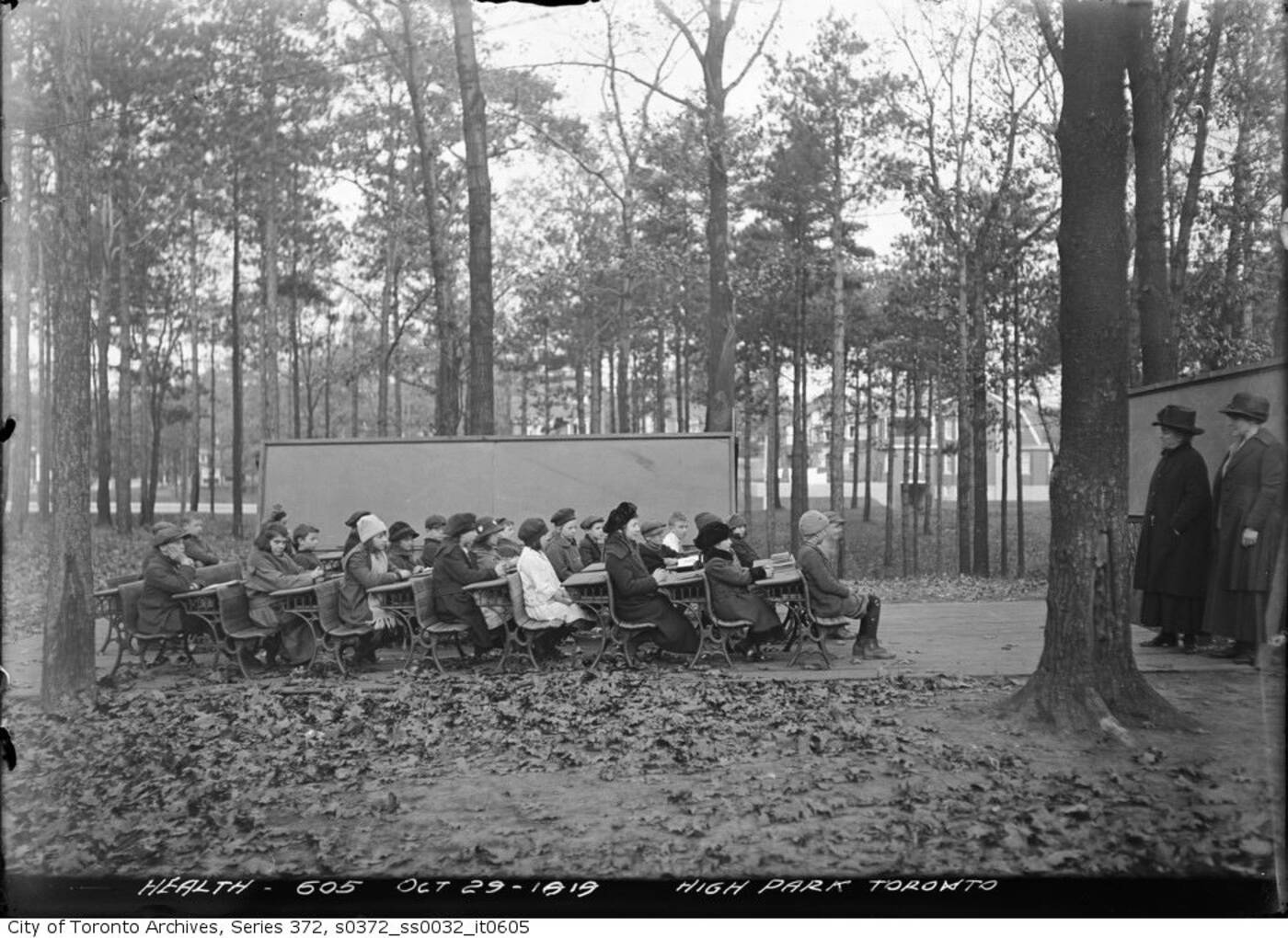

Counter to these imposing structures, it was also during this period that Toronto opened its first open-air schools, of which the High Park Forest School is best known.

This outdoor facility for tubercular and undernourished children ran from May to October to augment its students regular education.

High Park Forest School in the fall of 1919.

High Park's Forest School remained as a place for under-privileged children until 1963. At that time, municipally run summer camp programs took much of the burden off of open-air schools in providing education and care outside of the fall/winter term.

The mid-century period brought another wave of expansion for Toronto's school system, which is easy to spot today thanks to the modernist architecture of many schools from this period.

At the time, the Toronto Board of Education had its own architectural department headed up by Frederick Etherington and primary design architect Peter Pennington.

The schools from this period are an important part of the city's cultural legacy, even as some are under threat of demolition.

Davisville Public School. Photo by Robert Moffatt.

Lord Lansdowne (1961) and Davisville Public School (1962 - now demolished) are probably the most architecturally significant of Toronto's mid-century schools, but the two decades that followed their construction witnesses a surge of new schools across the city.

While each borough had its own school board pre-amalgamation, some of the major design principles were shared across Toronto. It's easy to place schools from this period even at a quick glance.

As was the case at the turn of the 20th century, a surge of school construction took place, this time to accommodate a city that was rapidly expanding both in terms of geographic development and overall population.

By the time the 1980s rolled around, school construction slowed as the construction of the previous decades left its mark. Some public schools were converted to the Catholic Board. Don Bosco used to be Keiller Mackay Collegiate Institute (1971) and Tabor Park Vocational School (1966) eventually became Jean Vanier.

The legacy of Toronto's school building boom in the 1960s and 1970s is still being felt today. Following amalgamation in 1998, the various school boards for each borough were united as the Toronto District School Board.

Figuring out just how to spread students out in a unified system is just one of the challenges that the TDSB faces today.

Throw in changing demographic patterns, increasing downtown density, the birth of new neighbourhoods, wild real estate values, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the task of managing our school distribution becomes hugely complicated.

North Toronto Collegiate. Photo by Oreo Priest.

We've seen novel deals brokered to revitalize schools through condo developments, like at North Toronto Collegiate, but such plans aren't always warmly embraced (i.e. John Fisher).

Over the last decade, the Board has undertaken the process of reviewing a list of schools that it could close and sell off.

The coming decades will pose many challenges for the TDSB with continued provincial pressure to shutter under-attended schools and development trends creating new pockets of density throughout the city.

Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments