The history of the Harbord Village neighbourhood in Toronto

Harbord Village is a tiny neighbourhood in Toronto nestled between the Annex and Little Italy. Known as both a residential and commercial area, it’s filled with family homes, restaurants, cafes and specialty shops.

Sometimes referred to as the South Annex, Harbord Village has a long history unknown to many Torontonians. According to historian Wendy Smith of Harbord Village, this flat neighbourhood was formed from the lakebed of Lake Iroquois during the last glacial period.

Indigenous people were known to frequent the area, hunting animals that were grazing.

The intersection of Spadina Avenue and Harbord Street in 1911.

This led the land, containing Harbord Village, to see competition among Indigenous groups, like the Huron-Wendat and the Senecas. In the 1760s, hundreds of Mississaugas took over the land before the British claimed ownership.

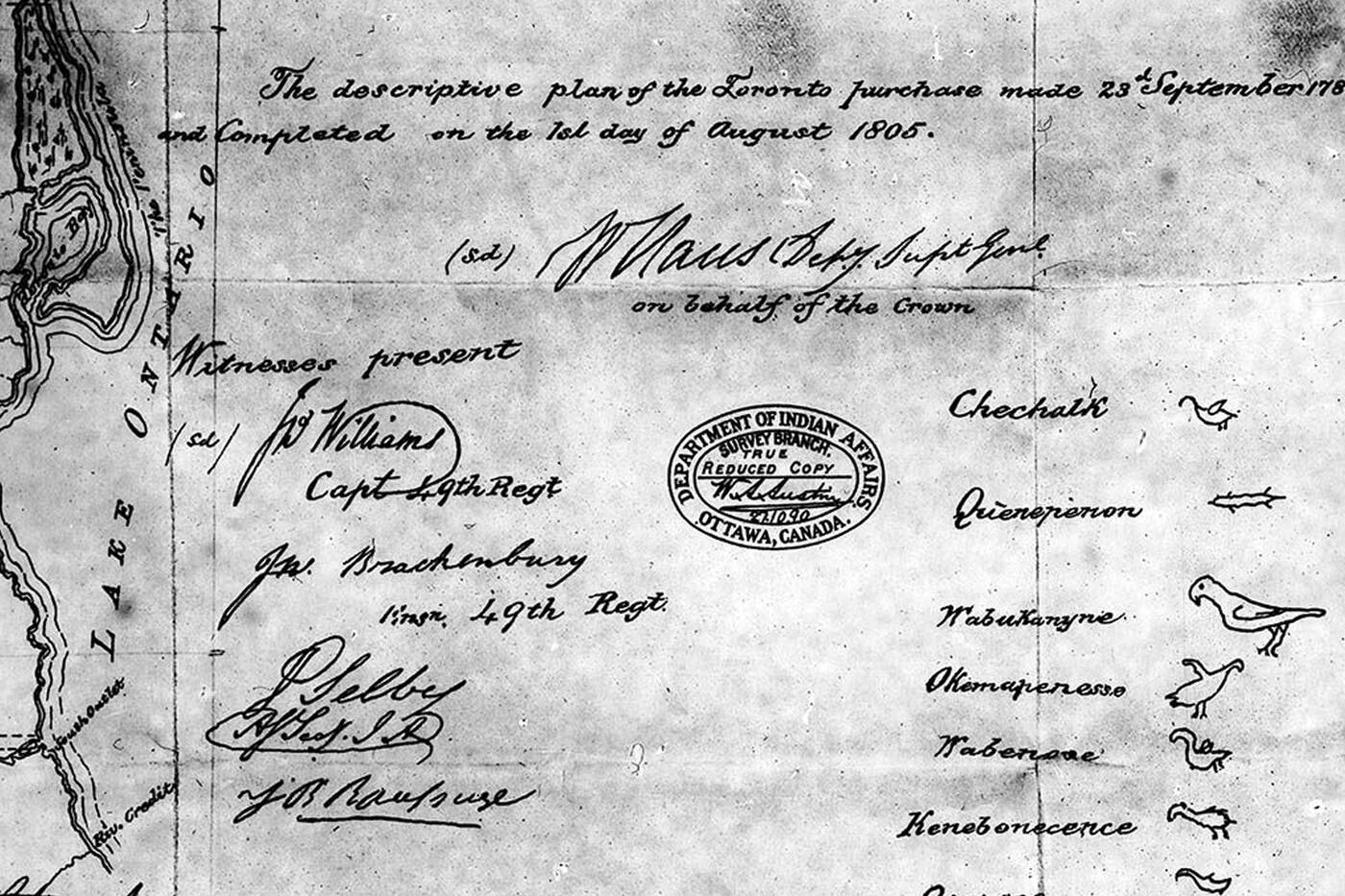

The 1787 Toronto Purchase

In 1787, the British colonial government purchased the land covering much of Toronto’s central metropolitan area under what is called the Toronto Purchase.

According to The History of The Mississaugas of The New Credit First Nation, the Toronto Purchase is extremely controversial because the Mississaugas did not understand the agreement in the same way the British did, as they did not know their rights to the land and its resources could be permanently signed away.

Signatures on the Toronto Purchase signed September 23, 1787, and completed on the last day of August in 1805.

In 1805, the document was revised to define specific rights for the Mississaugas. Despite this, most of the Mississaugas moved away from the area in the following decades. This was due in part to the large number of European settlers who came to the neighbourhood starting in the late 1790s.

The earliest subdivision of land in the area was done by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe in 1793, as a plan for the foundation of the town of York, which is present-day Toronto.

The land was mainly developed by six families, the Baldwin, Denison, Willcocks, Russell, Baby and Jarvis’.

Old cedar block pavement along Brunswick Avenue north of Harbord Street on November 1, 1899.

The Village evolved in the 1870s

Harbord Village began quickly evolving in the 1870s, with initial residents being mainly British immigrants. Roads were paved and homes were built to fill the need of the growing population.

New cedar block pavement along Harbord Street - Robert Street to Spadina Avenue in 1899.

This was the time when the Bay and Gable semi-detached houses that the neighbourhood is now known for began popping up.

It was largely a working-class neighbourhood, including men working in trades as well as a few white-collar workers. However, during the 1920s the more affluent families left the area to other, newer parts of the city.

View from the roof of Knox Church, Spadina Avenue and Harbord Street in 1910.

This allowed a much more diverse population to move in, including descendants of slaves who escaped from the United States, as well as immigrants from Europe, many of them working in the garment industry along Spadina.

According to Harbord Village History, this led the commercial part of the neighbourhood to begin catering to these ethnic groups.

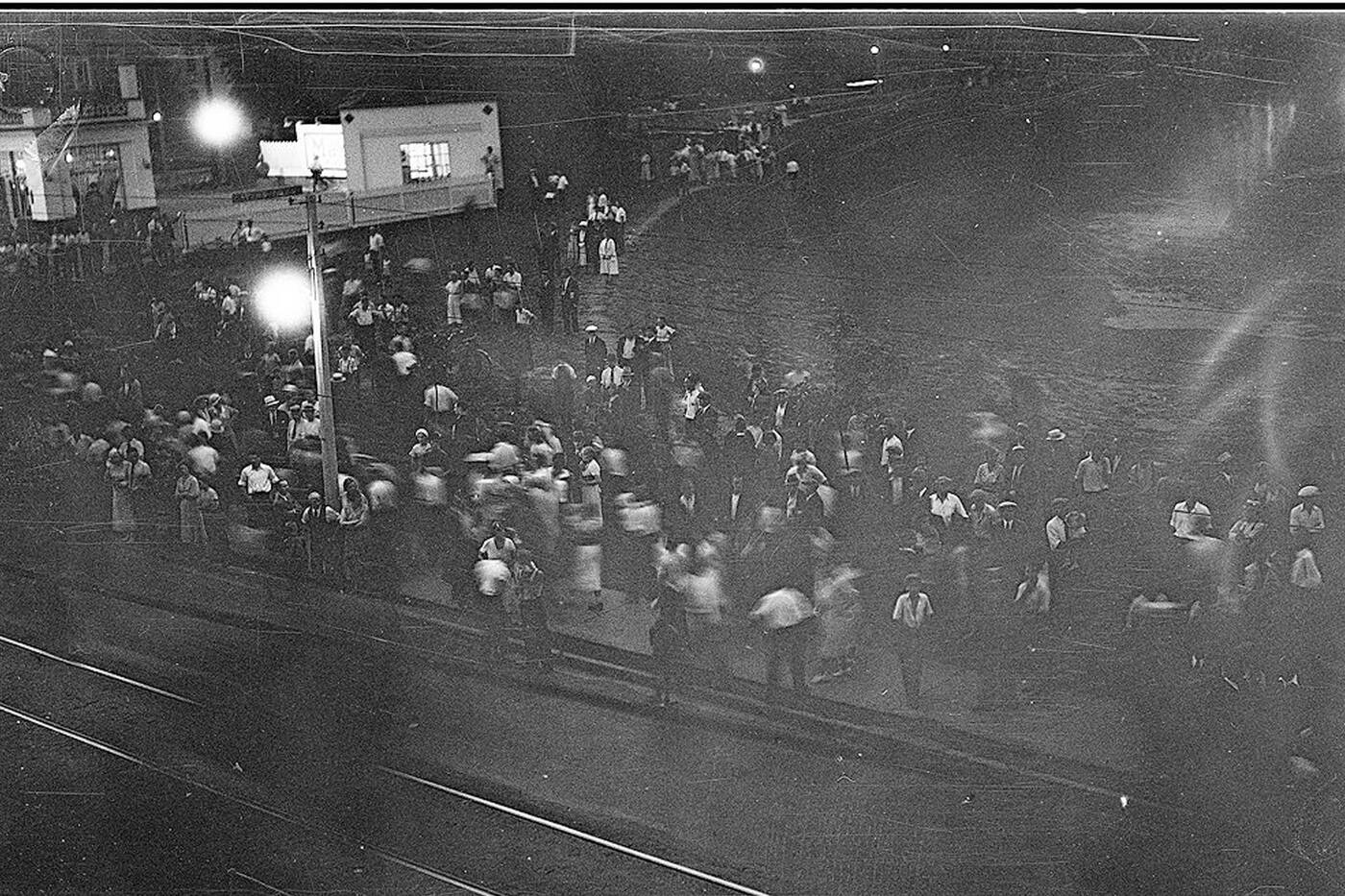

Jewish Eastern European immigrants were a large part of the demographic, but often felt excluded from the white, Protestant society that dominated much of Toronto at the time. In 1933, the neighbourhood came together when the infamous Christie Pits riot broke out nearby.

It started as a fight between fascist supporters and the largely Jewish Harbord Playground baseball team, and ended as one of the largest and most famous riots in the history of Canada.

Christie Pits riot on August 16, 1933.

Immigrants played a big role

The Jewish immigrants played a big role in the development of the neighbourhood, opening synagogues and many local shops. In 1943, the First Narayever Congregation (established in 1914) acquired 187 Brunswick Avenue where it stands to this day.

During the 1940s and 1950s Harbord Village was known for the abundance of bilingual families, speaking English as well as their native languages at home.

Unfortunately, the neighbourhood was still considered a slum and families who acquired wealth continued to move away.

These vacancies invited Italian and Portuguese immigrants to move in, buying homes from the Jewish families who were leaving the area. To this day, Harbord Village still has a significant Portuguese population.

View of Harbord Street from Spadina Avenue on June 13, 1944.

It attracted new residents in the late 60s

The City of Toronto planned to rid Harbord Village of its slum identity and replace the old houses with tall apartment towers. The planned Spadina Expressway inspired the city to turn Harbord Village into an up-and-coming neighbourhood, essentially at the cost of losing the character it was known for.

However, it was this character that ended up attracting new residents in the late 60s. Harbord Village steadily began gaining popularity with young professionals and university students who were drawn to its affordability and proximity to their campus and the downtown core.

As a result, only one block of houses was demolished and residents decided to form the Sussex-Ulster Residents’ Association (SURA), the forerunner of the Harbord Village Residents Association (HVRA).

In the end, only two high rises along Spadina were completed and the Spadina Expressway was cancelled, leaving Harbord Village to continue developing. The neighbourhood once again became an inviting place for young adults to settle down.

Harbord Village became known for its Victorian architecture, walkability and strong sense of community. The 1970s and 90s brought great gentrification to the neighbourhood, as professionals working and studying at the University of Toronto settled there.

In 1983, the Morgentaler Abortion Clinic was opened on 87 Harbord Street by Dr. Henry Morgentaler. Its existence sparked many disputes, with pro-life and pro-choice supporters both holding demonstrations.

This led to the clinic being fire-bombed by a pair of anti-abortion

activists in 1992. The building was eventually rebuilt and remains a solemn reminder of an important time in Harbord Village's history.

In the year 2000 SURA became HVRA, named after the neighbourhood’s Harbord Street. Through their work, a few streets in Harbord Village have been named Heritage Conservation Districts.

Unfortunately, the neighbourhood hasn’t been able to preserve all of its favourite places. In 2012, Harbord Village’s Toronto Women’s Bookstore closed its doors after serving Toronto for 39 years.

In 2013, The HVRA created the Oral History Project, to record stories from people who lived there between the 1930s and 1980s. It celebrated the neighbourhood's history through audio interviews, transcripts and historic photos.

This was done thanks to an $18,000 grant from the Ontario Trillium Foundation.

Harbord Village shows you that every street has a story and every neighbourhood plays an important role in this city’s history.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments