A history of how the death and destruction of cholera epidemics shaped Toronto

Three large cholera epidemics occurred in Toronto's history during the following years: 1832-1834, 1849, and 1854-1855 followed by a significant panic – though no epidemic – in 1866.

Each of these major outbreaks preceded and prompted the development or emergence of vital democratic and societal institutions in both Toronto and Canada as a whole.

Cholera – a waterborne bacterial illness, often fatal– was a significant force in colonial Canada. The maritime immigrant experience was one of the main avenues of increasing early colonial populations in the Canadas.

As early as the 1840s, colonial Canadian officials noted a link between port-of-origin and increased risk of 'zymotic' (infectious) disease on board maritime vessels.

Quebec Port in 1834. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Zymotic disease refers to a Victorian interpretation of infectious disease where illness was perceived to ferment in the body like brewers' yeast or fungi. Outbreaks of highly contagious diseases were particularly problematic in ports along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence during the 1830s and 1840s.

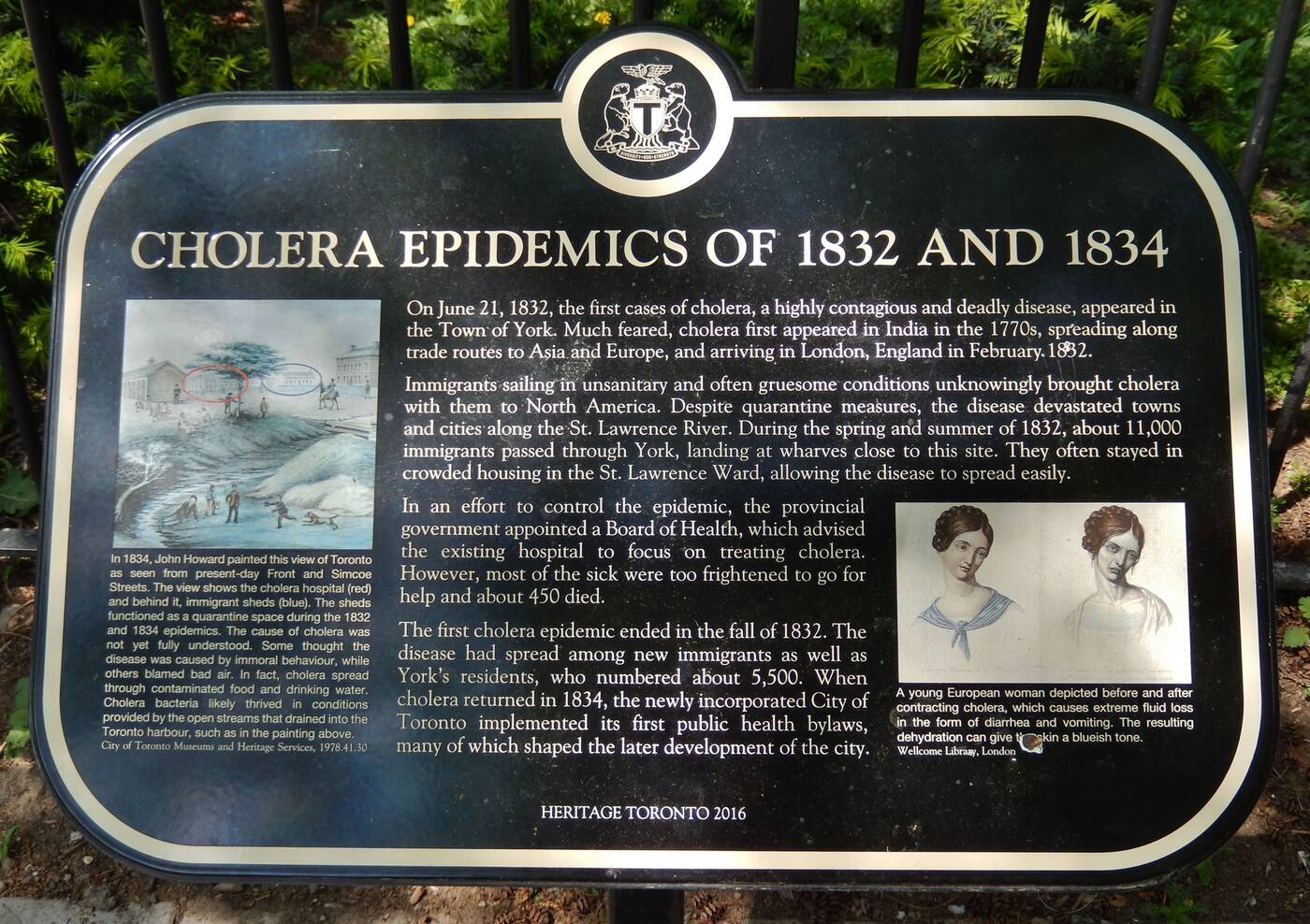

A young Viennese woman, aged 23, depicted before and after contracting cholera, Coloured stipple engraving, Italy (1831). Wellcome Collection.

Bruce Curtis in Social Investment in Medical Forms: The 1866 Cholera Scare and Beyond (2000) notes that the early colonial Canadian government was "prepared to abrogate individual liberties of property, privacy, and movement while specifying regulations for the conduct of individuals in relation to themselves and others" in order to address these inter-regional outbreaks of infectious disease.

Other common and challenging disease outbreaks in this era included diphtheria, malaria, measles, smallpox, and typhus.

Early 19th-century Canadian industrial cities along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence must be thought of as an interconnected series of municipalities due to their historic reliance on waterway access for transportation of goods, people, and trading services.

Easy-to-traverse road systems were not yet a common infrastructure item outside municipalities and rail networks were still in their infancy during this era.

Quarantine checkpoints were established at several points on the Gaspé Peninsula and at Gross Île just east of Québec City. Maritime vessels were ordered to anchor and fire a cannon to announce their presence to officials, though oftentimes vessels would sail right past – claiming ignorance of the laws.

"Cholera Plague, Québec." Painting by Joseph Légaré , circa 1832.

The quarantine checkpoint system created some of the earliest forms of statistical medical data in Canada, recording port-of-origin, number of passengers, classes and quantities of goods, and presence of fever.

Disease followed shipping and trade routes, as well as interregional migration patterns in the early to mid-nineteenth century. An outbreak of cholera in Caribbean port cities often preceded an outbreak in the Americas and Canadas several months later.

The presence of cholera or other diseases at a quarantine checkpoint or notices received from other colonial port cities of regional outbreaks in the mail were spread with public fervour.

At least one region – the Mississippi River trade network– went through extensive mail disinfecting programs in the nineteenth century to try and promote public health and safety while limiting spread of disease through contaminated mail items.

Disinfecting mail items was an attempt to prevent a breakdown of social cohesion and communication and subsequently functional societal operation in an era before rapid communication methods.

In "Social Investment in Medical Forms" (2000) Bruce Curtis calls public response to this disease phenomenon "cholera culture" as it involved an integrated approach involving actors on all levels from the international to the municipal, as well as the corporate to the individual in promoting knowledge of cholera transmission and promoting the elimination of transmission routes and vectors.

In an era before water and waste management systems, eliminating cholera and diseases at the source was a vital management routine coordinated and executed by regional authorities rather than colonial authorities across the Atlantic. It was functionally impossible for colonial authorities across the Atlantic to respond and manage outbreaks in a timely and thus effective manner.

Stephen Bocking, in "Constructing Urban Expertise" (2006), identifies the importance of technical expertise within urban planning procedures and how this facilitated "the emerging capacity of the city to regulate and provide for itself."

Outbreaks of cholera and other infectious diseases sparked the creation of institutions and regulatory bodies in the name of governance and promoting public safety. This regional authority over the health of its residents fuelled early notions of Canadian self-reliance, self-governance, and autonomy.

The sanitary idea – replacing the zymotic and miasmic theories of disease — did not gain popularity in Toronto until the 1870s, despite being introduced in London in the 1840s. This transition in understanding of disease transmission dynamics had vital impacts on democratic procedures in Toronto and the Canadas.

However, the sanitary idea was also closely tied to trends of 'moral environmentalism' and 'moral absolutism' where religious notions of moral and immoral behaviours impacted public policy. This model of public policy was pervasive in Canada until the late-twentieth century.

The Gooderham and Worts Industrial District was formed in 1831 on the west banks of the Don River Delta. This Industrial District was home to Upper Canada's grain processing centers which rendered grain derivatives, products, and by-products.

The Gooderham and Worts Industrial District expanded several times between the 1830s and 1860s, eventually housing multiple processing, distilling, and rendering plants.

Gene Desfor identifies in Planning Urban Waterfront Industrial Districts: Toronto's Ashbridges Bay, 1899-1910 (1988) that by-products of these plants included "refuse from a large number of cattle byres, or dairy and beef fattening yards, also being dumped into the marshlands… [eventually] there were seven byres with a capacity for more than 4,000 animals" dumping waste into the wetland and waterway systems of Toronto.

Ashbridges Bay marshlands in the 1890s. City of Toronto Archives.

During this era, the economic and residential center of Toronto was located in present-day Corktown – resulting in significant volumes of human sewage entering area waterways and forming a significant source of biohazardous pollution.

Some of the earliest technical reports for regional authorities indicate severe concern over the state of the Don River Delta, Ashbridge's Marsh, and the Inner Harbour of Toronto, as these environments were the common dumping ground for residential and industrial waste products.

1866 cartoon depicting cholera's waterborne dangers. George Pinwell.

This pollution further displaced First Nations communities and early residents (including a large Black community in present-day Leslieville) who relied on Ashbridge' Marsh and its connected waterways as a vital ecosystem for food, camping and settlement, and transportation.

1832 saw the Parliament in Upper Canada move from Church Street and King Street East to the present-day intersection of Front Street and Simcoe Streets. Parliament was located two kilometres west of the Gooderham and Worts Industrial District.

Cholera epidemics of 1832-1834 - heritage plaque (via Historical Markers Database). Heritage Toronto, 2016.

Adjacent to the new Parliament building were the City's Immigrant Sheds — infamous for their crowded conditions and outbreaks of disease.

In 1835, the first sewer was constructed in Toronto. This early sewer buried Russell Creek south of King Street, which had become extremely contaminated with feces and other waste products.

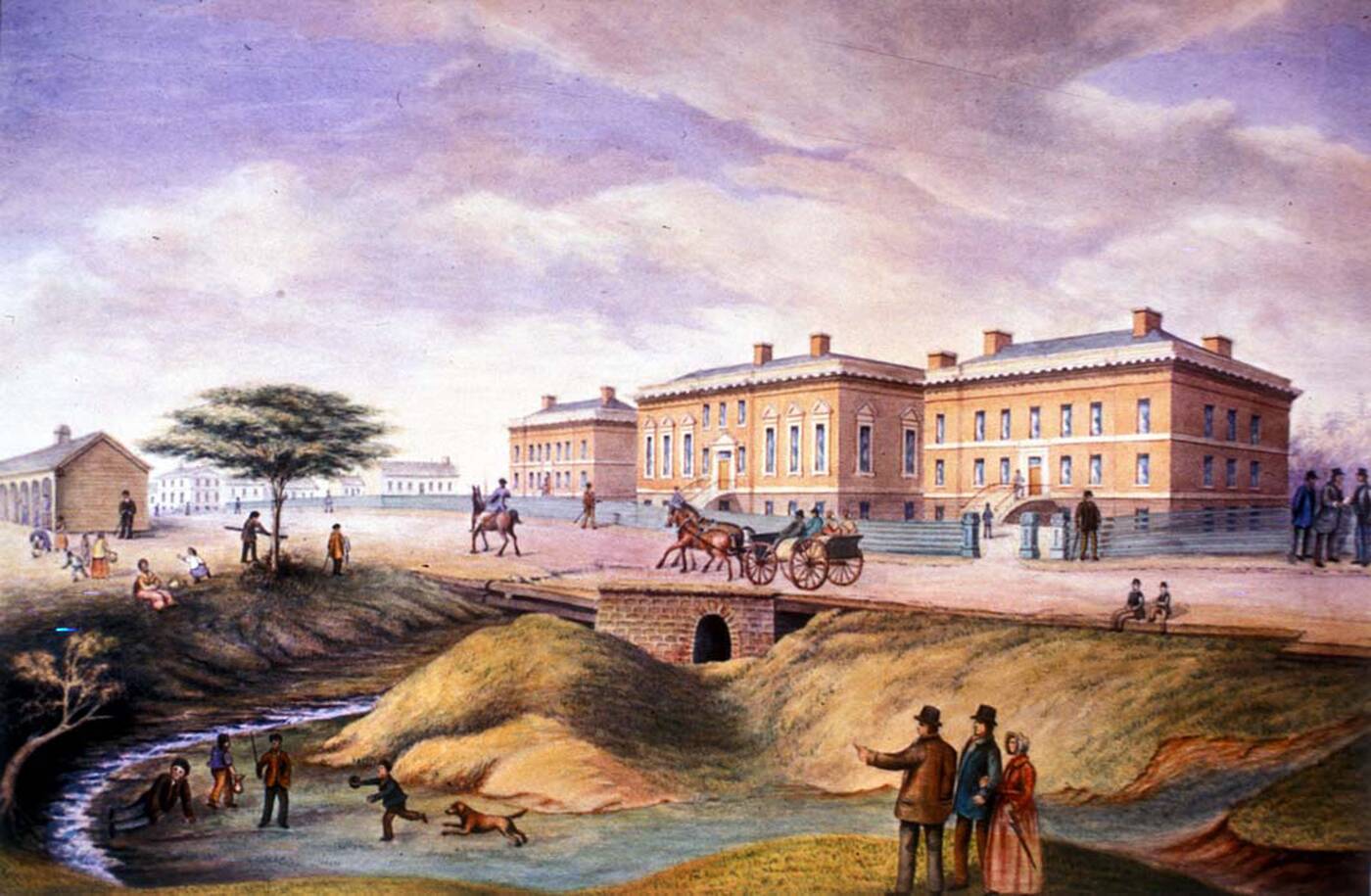

Russell Creek had previously flowed directly in front of the new Parliament Buildings (visible in this 1834 painting) and had become a smelly problem for those attending Parliament. The sewer drained, untreated, into the Inner Harbour.

Upper Canada's Third Parliament Building, 1834. Image via Ontario Legislative Assembly.

Six years later, in September 1841, provincial legislation was passed that incorporated Joseph Masson, Albert Furniss, and John Strang as The Toronto Gas and Light Company — Toronto's first municipal gasworks and waterworks.

The early waterworks reservoirs were officially reserved for firefighting, but public complaints to the officials hint at other uses, including consumption, domestic uses (laundry, cleaning, etc.), and recreation.

Within a few years, Furniss had been accused of poisoning the residents of Toronto after City Council voted to install the water intake pipe only a few meters away from the sewer output pipe in the Inner Harbour.

Regional authorities had identified a public problem, though had failed to fully identify the relationships, mechanisms, or vectors for regional disease outbreaks in relation to environmental contamination.

1849 saw a significant cholera epidemic along the St Lawrence and Great Lake waterways. Joseph-Charles Taché (1820-1894) was a Quebecois doctor and the Deputy Minister of Agriculture, who was working in the Saint Lawrence Region during the 1840s. Taché extensively documented his observations on cholera transmission along ports on the Saint Lawrence.

Joseph Charles Tache. Archives of Quebec.

This same year, Taché published the "Memorandum on Cholera" which introduced twenty public health laws and bylaws based on his experiences and observations managing the St. Lawrence quarantine checkpoint system.

These regulatory guidelines intersected city planning, housing services, transportation services, medical officials, port and waterway authorities, and judiciary forces in ensuring measures were followed to limit the transmission of cholera and to prevent other outbreaks.

This regulatory model was initially implemented in the French Québec City and Montréal and later adopted in English Kingston and Toronto the same year.

1853 was a pivotal year in the management of Toronto's water and waste management systems. Kivas Tully (1820-1902) – a city engineer, councillor, and port authority – published a report in 1853 urging immediate action to remedy the cesspool created by annual, natural flood events exacerbated by significant sewage and waste dumping on the east boundary of Toronto harbour.

Tully's report advocated for the re-direction of the Don River into the Ashbridge's Marsh via cutting a channel in the marsh and erecting a breakwater on its western boundary.

It is important to note that during this era the environment immediately east of the Don River Delta was still one of the largest continuous urban wetland ecosystems in North America.

Tully saw this wetland as having potential as a retention system for sewage and waste products from both the economic industrial and residential zones of urban Toronto. His vision had grave implications.

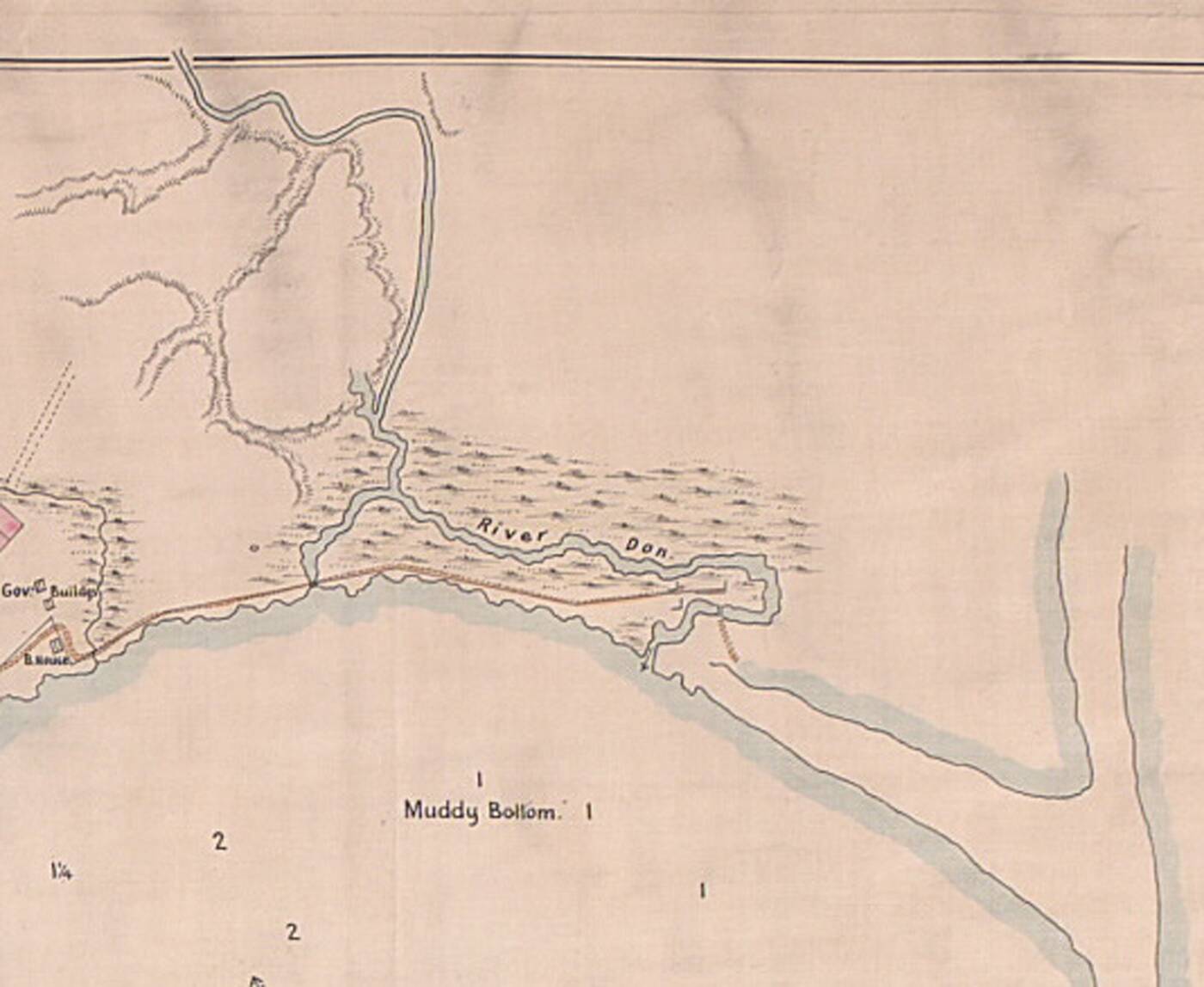

Don River Delta - 1823. Toronto Archives.

Residential sewage coupled with biohazardous waste products from thousands of cattle at the industrial rendering plants suddenly started flowing into Ashbridge's Marsh and stagnated. This resulted in the cholera outbreak of 1854-1855, which killed an estimated 5000 Torontonians — an estimated 1/6th of the population.

Many are still buried in cholera pits under Saint James Park, Toronto's former mass graves or public cholera grounds.

The year 1854 saw the emergence of infectious disease medicine in Canada through the establishment of the School of Medicine at Trinity College – now part of the University of Toronto – in response to growing numbers and severity of epidemic disease outbreaks in the region.

The establishment of a school of medicine in Toronto facilitated early notions of education and institutional research and development in the name of public health and safety, as well as public sector development in response to the 1854-1855 cholera epidemic.

In The Lancet in 1854, Dr. George Gibb (1821-1876) – a faculty member of Pathology and Surgery at McGill University and the St. Lawrence School of Medicine – published "On the Successful Treatment of Cholera in Canada" which documented his observances of treating cholera patients in ports along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence during the mid-nineteenth century.

Though cholera is bacterial, of note is Gibb's advocating for the treatment of cholera with a mixture of terpene camphor and calomel. The involvement of fungicidal calomel was a product of Victorian notions of zymotic medicine.

However, early notions of infectious disease management and treatment in the Canadas in the 1850s were plagued by misguided – though not malicious – attempts to prevent and treat infectious diseases.

One of Dr. Gibb's contemporaries – Dr. James Bovell (1812-1880) – a founding member of Trinity College's Faculty of Medicine –proposed and then put into practice the process of fresh milk, intravenous transfusions to treat cholera in the general public in 1854.

This process became the topic of both medical and public debate on grounds of its effectiveness and legitimacy.

Less than a decade later, Dr. Bovell was implicated in another stream of public debate and scandal over the safety of Toronto's hospitals after being responsible for the first documented patient death from anesthetic chloroform at Toronto General Hospital in January 1863.

Dr. Bovell was then later implicated in further accusations of implementing illegitimate or unfounded medical discourse after delving into 'moral absolutism.' That is, Dr. Bovell proposed governmental regulation of dress codes in public contexts and church fashion in the name of public health.

These overbearing notions of moral environmentalism and moral absolutism enacted by the regional authorities unfortunately fuelled public distrust in the newly emerging medical field and impaired voluntary reporting of disease outbreaks.

It is important to remember notions of accountability and consequence when translating theory into practice.

The implications wrought by misguided, illegitimate, and unfounded medical discourse and practice was a loss of faith by the public in both medical and governmental authorities during vital periods of both developmental and medical discourse in Canada.

At the height of the cholera outbreaks in the 1850s, the development and implementation of water and waste management systems in the city was marred by overly complicated municipal procedures.

Prior to the Toronto Sewer Boom of the 1880s, the majority of Toronto's residents' waste was either dumped in bulk into the waterways or directly into unhygienic cess and privy pits in the yards of their residences.

Several of these rivers were buried due to public health concerns over water quality and still flow in Victorian sewers under the downtown core of Toronto, causing structural instabilities above due to infill placed in Victorian times settling and shifting over the buried waterways.

Catherine Brace, in "Public Works in the Canadian City" (195), describes how residents had to petition the municipal authorities in order to implement sewer systems in nineteenth-century Toronto. To install a sewer, each block on the street required its own petition – "two-thirds of residents had to vote on it, followed by a city study on the efficacies of it."

This model became plagued by austerity measures, class distinctions, and civic in-fighting among neighbours and neighbourhoods. Such a model of democracy is fundamentally important, though the block-by-block specific requirements hindered progress in the implementation and integration of vital, life-saving water and waste management systems.

Brace (1995) further elaborated on this in-fighting as "an out of sight, out of mind attitude seem[ed] to have prevailed, producing a dichotomy between the willingness to pay for a sewer in one's own street and the unwillingness to pay increased taxes for a trunk sewer system."

Changing the common public discourse from one of financial drawbacks on the taxpayer to that of increasing individual property values elicited a greater and more appreciative public response as to the importance of implementing water and waste management systems.

Namely, having "a sewer into which one's property drained increased the value of that property and removed the smelly nuisance of the privy pit in the yard" while simultaneously reducing and largely eliminating a major vector for cholera and other infectious diseases.

1866 was the eve of confederation and independence of the Canadas. The year also saw American, Canadian, and Caribbean cities and ports gripped with mass fear of cholera outbreaks.

An outbreak of Asiatic Cholera in Continental Europe in 1865 and subsequent outbreaks in the French port cities of Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1866 fueled public fears that it would spread north and inland to the Canadas based on regional maritime trade routes.

This public fear was so strong it resulted in the formation and approval of the "Public Health Act" by Thomas D'Arcy McGee (1825-1868) in 1866, which was incorporated and carried over into Canadian legislation in the post-1867 Confederation period. McGee was the Canadas' Minister of Agriculture which was the position responsible for enacting quarantine measures.

The "Public Health Act" enacted measures around control, containment, and management in affairs leading to negative public health outcomes with the aim of mitigating or preventing them.

A significant component of this was addressing unhygienic and unsanitary housing conditions, stemming from the lack of water and waste management systems in residential areas, as well as economic industrial zones.

The "Public Health Act" allowed the government to appoint health wardens to enter private properties and point out sanitary failings regardless of the occupants' class or social position.

The decade following the Confederation of Canada saw several other favourable developments in the realm of public health and public sector development.

Delegation of state power over the individual and property to various jurisdictional boards and regulatory bodies in the name of public health fueled public discourse into the political foundations of health care.

Public concerns centred around the feasibility of only employing one Chief Medical Officer for the entire region. This model was problematic in that a single individual would be responsible for all decision-making, and subsequent policy influence, drafted per personal biases and personal stakeholder interests in the relevant proceedings.

Regardless, outbreak of contagious and deadly disease and subsequent containment and management fuelled ideologies around self-governance, self-reliance, and autonomy in the Canadas and clearly influenced confederacy through the incorporation of pre-colonial, regionally-created health models into official, post-Confederation national health policy.

Medical committees attempted to allay fears of hygiene and sanitation-based bias through announcing the strategy of employing a bilingual doctor to address both English and French civic and cultural interests. This doctor had ten police officers at his disposal to inspect people's yards for privies, cesspools, and stagnant water.

In 1877, the Chief Medical Officer and health wardens were granted the delegated authority to approve sewer installation without city council approval.

It is important to note that Toronto City Council previously held the power to approve the installation of sewers without a public petition or consultation process, but often did not out of concerns of constituents becoming irate over increased taxes as a result of the infrastructure projects.

The 1880s saw extensive developments in Toronto's water and waste management systems coupled with strong regional market forces and industrial prosperity.

The Toronto Sewer Boom of the 1880s resulted in thousands of homes being connected to water and waste management systems, with miles of sewers being built in a number of years compared to meters of sewers per year near the completion and final integration of the waste management system in the early 1890s.

In 1889 a report was issued about the specific sanitation and health problems associated with the significant environmental contamination of Ashbridge's Marsh with encouragement that the situation be addressed by authorities in a timely manner.

However, large-scale waste management system installation declined in the 1890s due to an economic depression, with Mayor Robert John Fleming (1854-1925) eventually cancelling the program in 1892.

In 1892, a significant public health and public sector scandal also unfolded in Toronto - involving fiscal mismanagement and apparent fraud during proposed land transferral for alleged containment, remediation, and treatment of the contaminated industrial environments at the Don River Delta and Ashbridge's Marsh.

This scandal was defined by a mysterious public entity known as the Beavis and Brown Syndicate.

The Beavis and Brown Syndicate proposed to municipal authorities that in exchange for reduced property tax and an exclusive monopoly for commercial activities on the lands for 45 years, they would undertake the costs and duties of environmental remediation of Ashbridge's Marsh in the name of public health.

Despite these proposed arrangements, the syndicate repeatedly refused to reveal the identities of its financiers, board members, and employees. This elicited public and political suspicions and accusations.

Bizarre financial transactions and exemption policies dotted the documents, with one report indicating the funds were accessible in London – and another a few days later claiming the syndicate did not and had never existed.

Accusations arose that the board members were local aldermen and councillors who would benefit from developments along the eastern boundary of the harbour, primarily for wharf and quay development for incoming ships, which would bypass navigation around poorly dredged Inner Harbour channels.

This scandal fuelled public discourse and distrust in the abilities of regulatory government bodies to enact unbiased change without publicly accessible data and fiscal monitoring protocols in place.

Toronto has a complex history in regard to the relationship between the management of infectious disease and stewardship of its lands and waterways.

Rampant and unchecked industrial and residential activities in the early and mid-nineteenth century created a significant public health hazard through mass biohazardous contamination of the Don River, Ashbridge's Marsh, and the Inner Harbour of Toronto.

Overly complicated colonial administrative policies in elements of public infrastructure design and implementation resulted in significant delays in vital water and waste management systems, which could have saved thousands of lives.

A lack of accountability for early regulatory boards resulted in public mistrust of governing authorities, resulting in diminished interactions between the medical system, government agencies, and the public.

Significant lessons could be learned not only in the history of Toronto as a city, but in approaches and management of future public infrastructure, public health initiatives, and land stewardship projects.

City of Toronto Archives, Series 376, File 4, Item 47

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments