This building is almost all that remains of Toronto's lost shipbuilding industry

20 Lower Spadina Avenue is one of a declining number of buildings in downtown Toronto which have direct historical associations with Toronto's maritime (shipbuilding) industries and port-related activities.

Completed in July/August 1919, 20 Lower Spadina Avenue originally housed the offices of the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited and marked the chief entry point to its shipyards.

The site of 20 Lower Spadina Avenue was originally part of the Toronto Harbour and was infilled between 1917 and 1919. Until the late 1970s and early 1980s, 20 Lower Spadina Avenue sat directly on the waterfront near the head of the Spadina Avenue slip and wharf.

Land infill projects during the late 20th century resulted in the building becoming cut off from the waterfront, where it is now situated approximately 80 meters north of the shoreline.

1947 aerial photograph showing 20 Lower Spadina and surrounding industrial context.

The Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited – also known as the Dominion Shipbuilding and Repair Company — was formed in 1917 by Christoffer Hannevig (1884-1950).

Hannevig was a Norwegian financier who purchased the Thor Iron Works in Toronto with capital investment of $2 million contributed by several investors, including J. P. Morgan & Company of New York City. Adjusted for inflation, this is approximately $45 million in the present era.

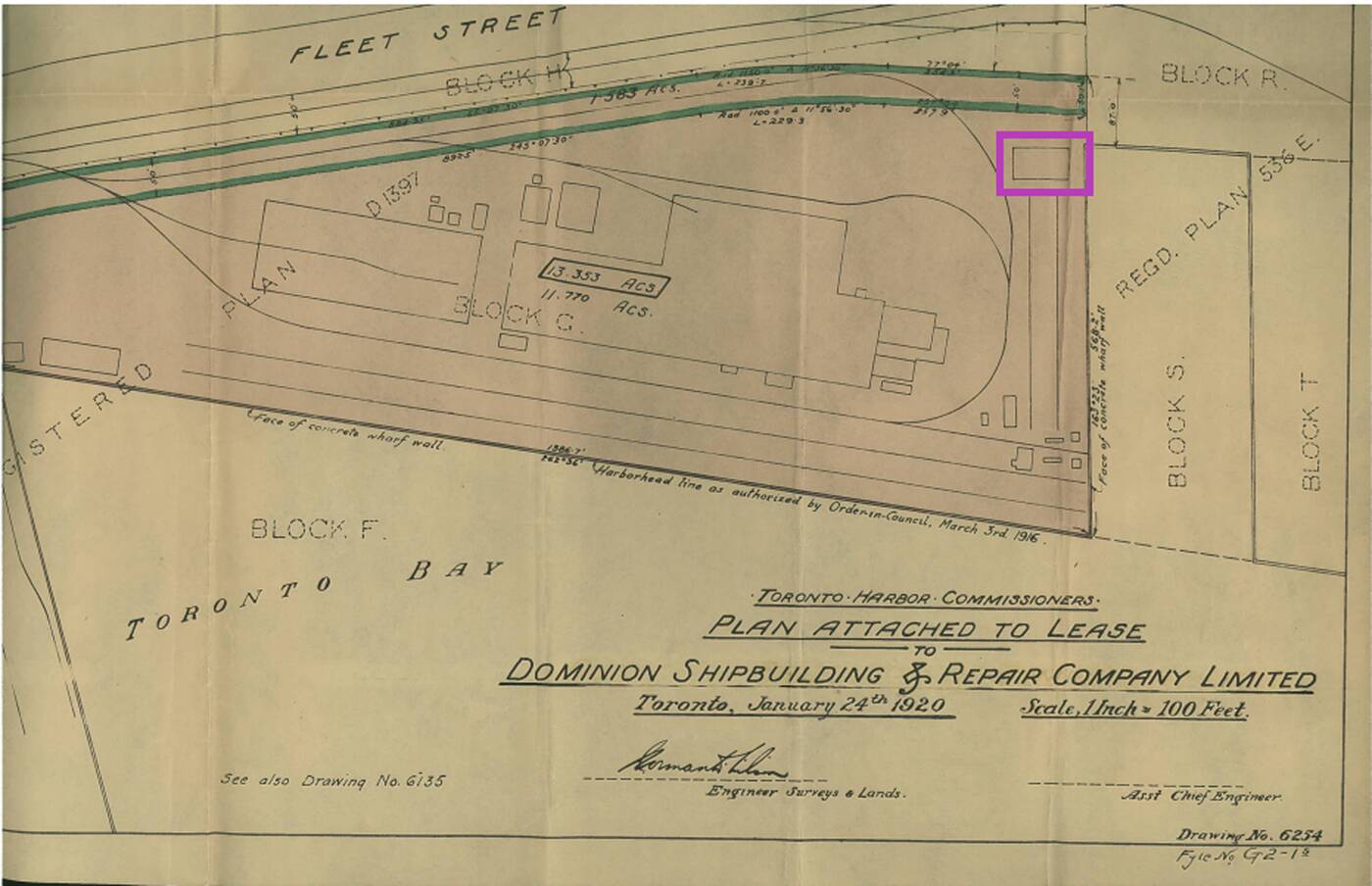

The Thor Iron Works was situated on approximately 15 acres along the waterfront between Bathurst Street and Spadina Avenue and were leased from the Toronto Harbour Commission.

Michael Moir notes in Shipbuilding and the Waterfront Plan of 1912 (2008) that as of Hannevig's 1917 purchase, two-thirds of the shipyard site was still underwater and slated for land reclamation by the Toronto Harbour Commission.

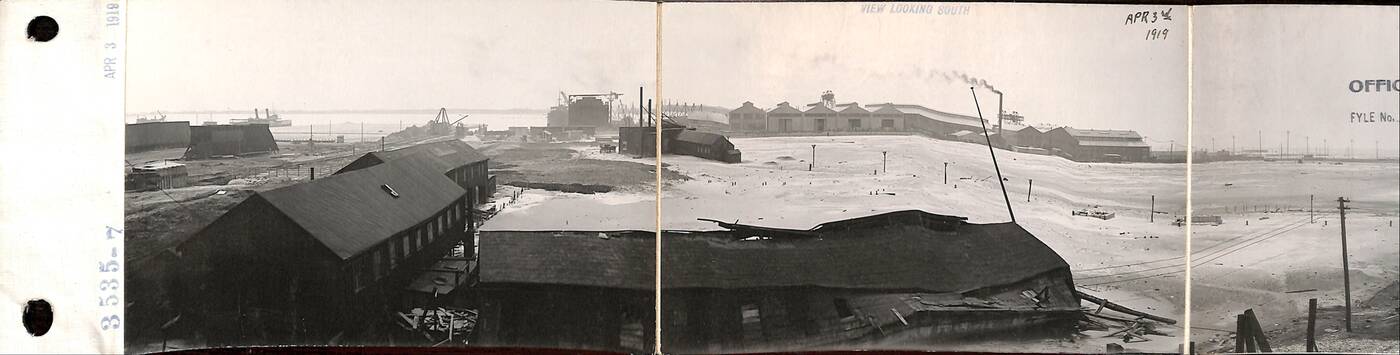

The vicinity of 20 Lower Spadina captured before the building was constructed.

Harsh winter weather coupled with a catastrophic fire that destroyed part of the former Thor Iron Works shipyard in April 1918 delayed initial operations of the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited, including both land reclamation and shipbuilding.

The land was leased to the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited in 1920.

In 1918, near the end of World War I, The Globe newspaper noted that shipbuilding was considered "one of the fields of industry that can be depended upon to absorb a considerable portion of labour that is being released from strictly war business."

Planning for the post-World War I economies and industries of Toronto was specifically noted to have been one of the contributing factors for the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited, specifically selecting and purchasing the site of the Thor Iron Works.

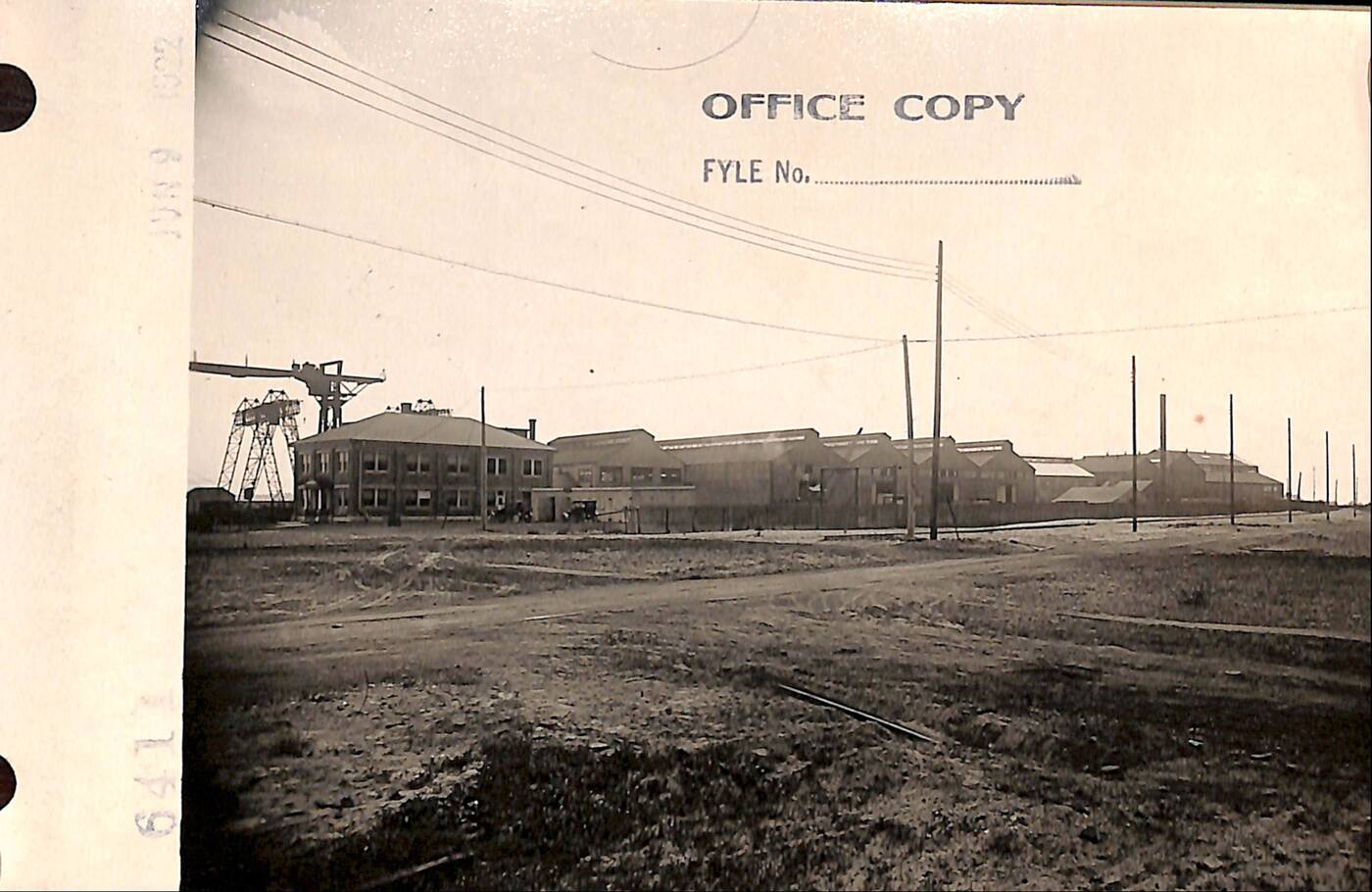

The shipbuilding operation pictured in the 1920s.

During World War I, Hannevig had created a business empire and was also connected to the Newfoundland Shipbuilding Company Limited; the Jefferson Insurance Company; the Liberty Marine Insurance Company; and the North Atlantic Insurance Company.

However, he experienced serious financial problems after the United States requisitioned 27 of his ships for wartime use in 1917. Of the 27 ships that were requisitioned by the United States for wartime use, Hannevig did not receive compensation for 18 of them.

Despite this, at the end of World War I in 1918, Christoffer Hannevig announced plans to construct a shipyard in New Jersey near New York City to construct ships for Norwegian shipping interests. This American site was operated under the name Christoffer Hannevig Inc. and its vessels sailed under the Norwegian flag.

In March 1919, Toronto newspapers happily reported that the Dominion Shipbuilding Company constructed 4 ocean-going freighters in a one-month period. By July 1919, Dominion Shipbuilding employed at least 1500 individuals.

By June 1920, the Dominion Shipbuilding Company had constructed seven ocean-going freighters. The seventh ocean-going freighter was the Gonzaba, which was constructed for the Gulf Navigation Company of New Orleans.

Despite this shipbuilding boom, the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited was a short-lived venture.

The company entered into bankruptcy, insolvency, and liquidation in July 1920.

The Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited provided three reasons for this: insufficient capital; labour and management; and the inability of the company to collect its debts. Hannevig and Hannevig & Company were named as the chief debtors in subsequent legal proceedings.

Shortly before this, in April 1920, the Metal Trades Union was negotiating a wage increase for metalworkers at the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited. Dominion Shipbuilding proposed increasing the wages of their metalworkers by 10% to 85¢ per hour, whereas the union was requesting a wage of $1 per hour.

The declaration of bankruptcy and insolvency resulted in a protest by the unionized workers of the shipyard that eventually evolved into a significant legal and political case.

This arose due to suspended operations and unpaid wages as a result of the Dominion Shipbuilding Company going bankrupt; as well as the failure of the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited and the Canadian Government to meet promises that were made during World War I for postwar employment of soldiers at the shipyard.

Notably, the Dominion Shipbuilding Company purchased victory bonds during World War. A message from Sir B. Edmund Walker (1848-1924) — that the Dominion Shipbuilding Company sponsored — about establishing a peace trade in postwar Toronto – published a day after the Armistice of 11 November 1918 – has been included with this article.

During this time, Sir Walker was the President of the Canadian Bank of Commerce.

Amid the strike, union members were concerned that workers from outside the company and/or Toronto would be brought into Toronto to complete half-finished vessels and outstanding contracts at the Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited shipyards. Their concerns were valid.

By August 1920, around one-third of the 800 mechanics formerly employed by Dominion Shipbuilding had been placed in other positions within their trade in both Toronto and elsewhere in Ontario through actions undertaken by their union.

In November 1920, Toronto City Council authorized the Transportation Commission to hire some of the 20,000 unemployed men in the City of Toronto to "commence work on the ships […] lying in the yards of the Dominion Shipbuilding Company."

Later, in December 1920, workers were brought in from the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company in Collingwood and the Henry Hope Company in Peterborough to finish 2 partially completed government vessels that were at the Dominion Shipbuilding Company shipyard while the Local 128 of the Iron Shipbuilders' Union picketed outside.

The shipyard continued to produce ships for existing contracts through June 1921.

By mid-1921, all of Hannevig's other business ventures had gone into complete insolvency. 20 Lower Spadina Avenue and the surrounding shipyards were sold in attempts to pay some of the more critical debts.

Following 1921, other uses of 20 Lower Spadina Avenue included uses by Roger Miller and Sons – contractors (circa. 1927/1928); Kilmer, Gibson and van Nostrand Limited – contractors (circa. 1929/1930); and Toronto Elevator Ltd. – a grain elevators company (circa. 1938). I would like to thank the Ports Toronto Archives for their assistance in identifying past uses of the building.

20 Lower Spadina photographed on June 9, 1922.

Later maritime uses of the former Dominion Shipbuilding Company Limited shipyard area included the manufacturing of allied minesweepers during World War 2 for the Dufferin Shipbuilding Company Ltd.; the Toronto Drydock Company Ltd.; the Toronto Shipbuilding Company; and Redfern Construction Company.

As of 1997, the building was tenanted by Galerie Céline Allard – a local art gallery.

As of the early 2000s, the 20 Lower Spadina Avenue building was owned by the Corporation of the City of Toronto. The 20 Lower Spadina Avenue building is presently – as of 2023 – tenanted by the Centre Francophone de Toronto (Centre Francophone du Grand Toronto) and the Broad Reach Foundation for Youth Leaders.

In the 1990s, 20 Lower Spadina Avenue was flagged by the Toronto Historical Board as having "significant heritage value but [was] not designated" or listed at this point in time.

In April 2021, I re-nominated the property for heritage status, albeit the City of Toronto has not provided any updates on this nomination since that point in time.

I am hopeful it may be added to the City of Toronto Heritage Register in the future as a rare surviving example of Toronto's maritime shipbuilding history.

Adam Wynne

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments