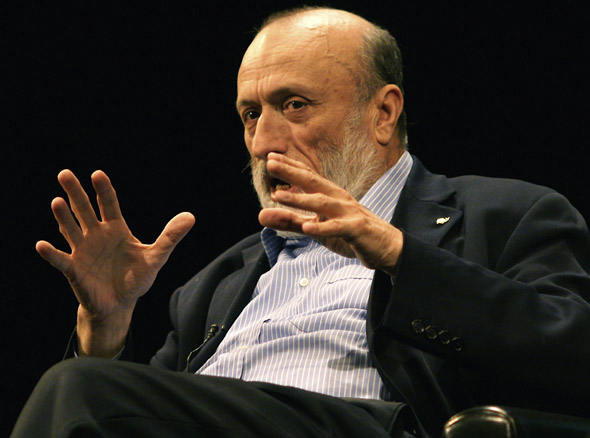

An Evening of Conversation With Carlo Petrini

Carlo Petrini knows a thing or two about food. He's got a thing or two to say about what we're doing right and wrong about ensuring the sustainability of our planet's food supply.

"The bees in Europe are dying. The pesticides that we're giving them are making them crazy.... Environment, Climate, Financial crises: Greed of man is the reason of all of them."

These are some of his convictions, which he shared at a talk last Saturday evening at Miles Nadal JCC's Al Green Theatre, presented by the Planet in Focus international environmental film and video festival, in association with the Italian Cultural Institute in Toronto.

Petrini is an Italian author and pioneer of the worldwide Slow Food movement, which aims to re-evaluate the agricultural processes, food production, distribution, preparation and consumption methods, which place food at the centre of human activity. Last year he received the Planet in Focus International Eco Hero Award.

The event was billed An Evening of Conversation with Carlo Petrini and I found it both inspiring and frustrating.

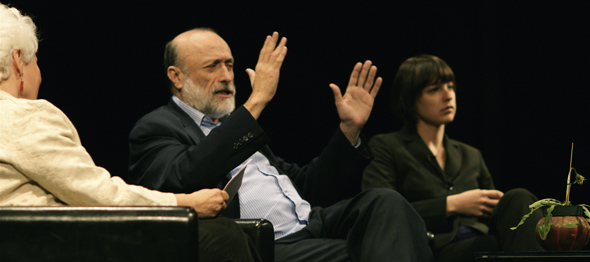

Harriet Friedmann of the Munk Centre on International Affairs was the moderator, but she did little other than give him a brief introduction, give him a wilting dandelion and ask him a few questions.

Petrini didn't speak any English, but he brought a rather proficient translator with him. This slowed down the proceedings somewhat, as we had to listen to every sentence (or part thereof) translated on the fly.

Petrini would reply in Italian, going on many tangents for several minutes before another question was asked. The experience felt like I was watching a really long foreign film with subtitles. Listening to him talk through an interpreter often slowed down the momentum of his message.

As for the content of his talk, I found it rather inspiring. The "evening of conversation" started out with a screening of a short film, which followed a chatty 78-year-old Italian farmer in his field, lamenting the fall of the farmer's role in food production.

"The farmers have always been the last ones," said Petrini. "There will come a time where we need to turn back, and the last ones will become the first ones. The farmers will be the first to bring us out of this situation. This is why we need young farmers. The technology and the traditional knowledge are not at the same level, so there's no dialogue.

I began to wonder if there would be any dialogue in this presentation. It was mostly Petrini going on and on, and little actual conversation. Not that he didn't have anything important to say....

"Traditional knowledge was based on observation and had an oral tradition. Even today, in poor countries, the old people speak and transmit the knowledge this way."

Petrini's message was that we need to give value to the food, and not consume more food. In the fast-paced culture in which we live, it's no wonder we've had a shift in our values. Perhaps there's some merit to slowing down and taking stock of our position and the position we give to food in our lives.

"People complain about olive oil price, not car oil price. The price of the dirty oil we put in cars is the same price as the olive oil. We must change our values.

Petrini went on to explain how, in 1972, families spent on average 32 percent of their income on food. And that today it's only 14 percent. But we spend 12 percent of our income on the mobile phone.

"Everybody's calling, but we don't know why we're calling.... We should go back and give the value to the right things. Put food in the central place. Have a holistic view of food. Don't give it credence as just fuel. The governance of limits is the new perspective. If we overcome the limit, the earth will die, and with it so will we."

Petrini gave examples of over-consumption in relation to our planet's production. "In Italy, everyone eats 90 kilos of meat per year. In America, it's 125 kilos. If everyone around the world ate as much, we'd need five planets to keep up. We need to change our eating habits."

He also blamed Mad Cow Disease on the universities of the West. "A farmer would have never given sheep to a cow to eat."

Petrini said he spent the earlier part of his day visiting several farmer's markets in Toronto and was quite impressed.

"I saw some very good examples of new things. I think these virtuous practices will be our future. We live in a period that's very similar to the fall of the Roman Empire. It took three centuries to break down. Out of this we will grow a new renaissance. This situation will produce a new humanism, or at least I hope it will."

He said we need to be building biodiversity from the bottom up and protect this creativity. "The farmer's markets were borne here in North America. We used to have them in Italy in Medieval times, but we lost them because all the markets became property of the commercial markets. So we're learning from you too. This is a country where so many cultures intersect. Don't give your soul, your heart to the multinational corporations, but build from the bottom up.

"When I first arrived in the US, they had 2 types of beer. One was Budweiser and I can't remember the other. Now, there are 4,000 microbreweries. This is the real biodiversity."

One of the more interesting notions brought up was what Petrini called The Governance of Limit, which he said was invented in the 6th Century after the death of Christ. He gave an example of Trappist beer produced by monks in a Belgian monastery. They make exactly 30,000 bottles of beer per year, in accordance to the strict rules in the abbey.

When asked how he sees biodiversity working in a city the size of Toronto, he said that this worries people in Italy much more than in Canada, because here we've got a much bigger area of land.

"In Italy we're very tight and we're destroying our land. During the last 80 years, we have put cement on the fields. We cannot continue to take the agricultural lands. We need to rebuild the relationship between city and rural areas. Urban agriculture needs to be sustained."

Petrini said the main reason of environmental disasters is food production. "Cows produce much more CO2 than all the cars around the world. The main reason is the agriculture and food production. It's here we should intervene and do something and work on this. We also need to change our relationship with gastronomy.

"A gastronomer who is not an environmentalist is stupid. And an environmentalist who is not a gastronomer is boring."

One of the more surprising notions Petrini brought up concerns hospital food.

"Hospitals should produce organic foods grown locally and cook decent food. For many, it's unclear that the food is part of the therapy. Good food in hospitals will help people recover better. After working with hospitals in the UK, they're wasting 50 percent less food. It costs them a bit more at the outset, but it's economically sound.

"It demonstrates that it's possible to make it more sustainable with more people consuming, due to higher demand. We should conquer the right for good, quality food for everyone. Otherwise it will become something for the elite and there's no future in it."

A lot of what I heard in this talk made sense. The real challenge is convincing enough people and corporations to change their mindset so that some of the notions, ideas and philosophies are put into practice.

Photos by Roger Cullman.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments