Interstellar and the birth of IMAX in Toronto

Since its inception, the movie industry has always relied on gimmicks to get people out of their homes and into the theatre. From the advent of sound, to colour, 3-D and DTS multi-channel audio, innovation was mostly driven by intense competition with rival mediums like radio, television and now the internet. While IMAX may seem like yet another cynical studio ploy to increase their bottom line by charging more money per ticket, it actually began in Toronto with an altruistic vision for Canada's place in the cinematic order of things.

From at least 1939, with the establishment of the National Film Board of Canada, it became apparent that apart from a few aberrant titles, Canada was simply not interested in feature length narrative film making.

While Hollywood churned out American mythology as easy-to-digest assembly line entertainment, Canada was happy to be globally known for its animated shorts and documentaries, guided by the vision of Scottish NFB commish John Grierson. It made no financial sense to try and compete with the raging bull next door.

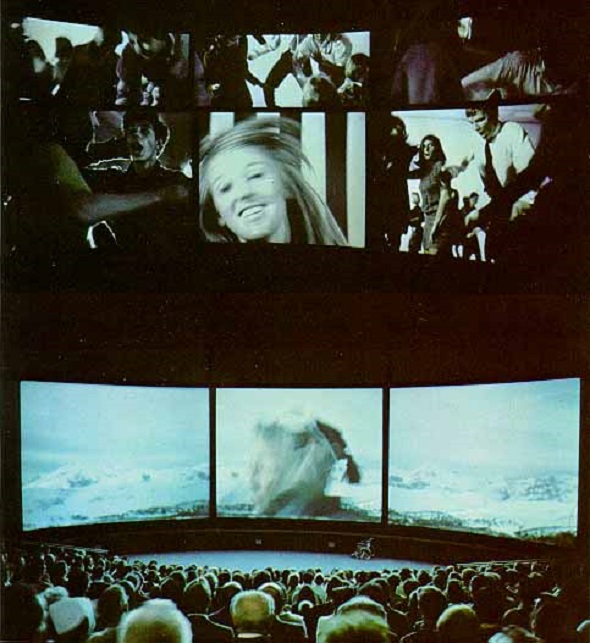

In 1967, the paradigm shifted dramatically with the films created for Expo'67: a celebration of Canada's centennial which still represents a high watermark for Canadian idealism. Experimental multi-screen films such as We Are Young, A Place to Stand, and Canada '67 blew minds and singed eye-balls with their radical technique. Suddenly viewers were active participants in these non-fictions, avant-garde travelogues with teeth, as opposed to passive observers.

Toronto native Graeme Ferguson directed the Expo'67 film Man and the Polar Region, a breath taking multi-screen exploration of the Arctic while his brother-in-law Roman Kroitor directed the NFB's official offering Labyrinth, often cited as the most important film of Expo '67. Both films relied on multiple massive screens, concurrent images, immaculate cinematography and the appointment of sensory stimulation over traditional storytelling.

On the heels of their Expo'67 success Ferguson and Kroitor realized films of this nature were the best way forward not only for Canadian film, but the art in general. In 1974, Ferguson stated "to draw people out of their homes, especially in the future when many people wall have wall-screen televisions, theatres are going to have to offer something very special - an experience which cannot be duplicated anywhere else".

Ferguson and Kroitor enlisted the help of engineer William Shaw to help develop a new technology which could accommodate the lessons learned from creating the Expo'67 films: a bold vision encompassing stadium seating, gigantic screens and surround sound.

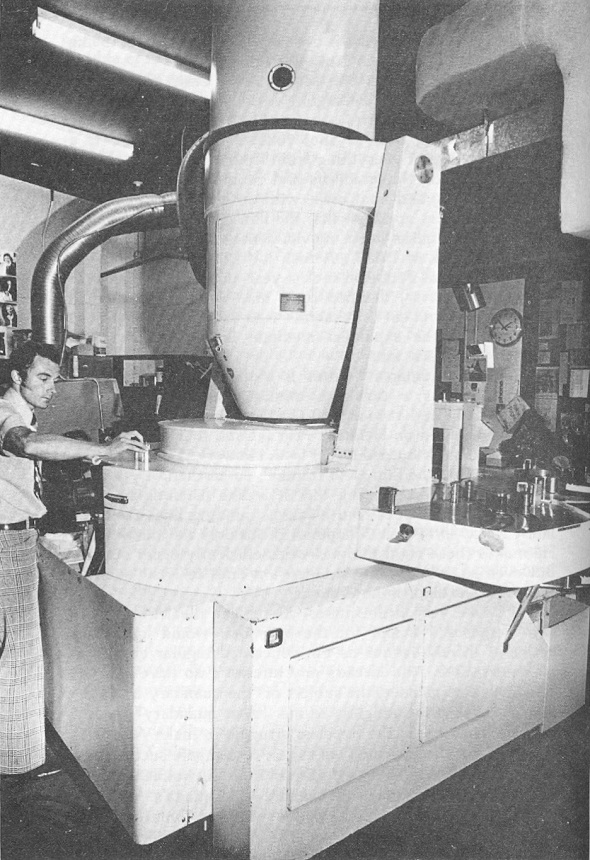

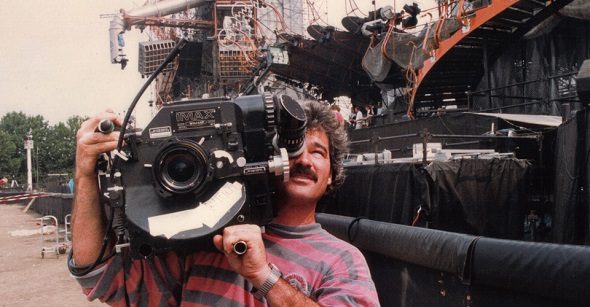

Shaw created a camera and projector which could offer extraordinary picture quality (a film frame which could produce approximately 18 thousand lines of horizontal resolution) and handle film stock 10 times larger than conventional 35mm picture frames. Not even 70mm was large enough to contain the kind of mind-blowing imagery this cadre of film makers wanted to present. With the aid of Ferguson's business savvy high-school friend Robert Kerr, The IMAX Corporation was born.

The first IMAX production to use this revolutionary technology was Tiger Child, featured at Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan. However the IMAX Corporation knew they needed a permanent base from which to build an audience and experiment with new ideas. Enter Ontario Place, another innovation influenced by the opulent majesty of Ontario's Expo'67 pavilion.

In 1969, Premier John Robarts announced the creation of Ontario Showcase (later Ontario Place), a collection of pavilions on the waterfront which would serve as an Ontario historical museum and family park featuring restaurants, a marina, live concerts, and an Expo-styled Dome where unique films would be screened. Architect Eberhard Zeidler delivered a six-storey-high screen upon which IMAX films could be projected - the iconic Cinesphere.

In May of 1971 the Cinesphere theatre was open for business, premiering another IMAX film entitled North of Superior, directed by Graeme Ferguson. The 18-minute long film (the maximum length of time a single IMAX reel could hold at the time) brought to life the geography of the Lake Superior region with rich aerial shots and a sonic depth unheard of in any film previous.

The new cameras used in filming had literally been put together with the help of duct tape, while dangerous helicopter stunts performed to capture perfect shots illustrated the daring and adventurous roots of cinema were alive and well at IMAX.

Line-ups stretched for hours as viewers flocked to see what all the fuss was about. Author John Hofsess described it as "the pleasure in seeing Ferguson's film is similar to the feeling one has in seeing a D.W Griffith or Sergei Eisenstein film for the first time; the director knows he is breaking new ground. The dimensions of the film medium will never again be the same". Viewers were even warned to close their eyes if they experienced any discomfort due to eye perception over-ruling the inner ear balance.

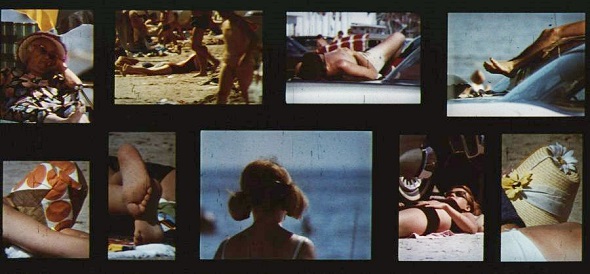

Seen by over 1 million people, North of Superior is considered the most widely seen Canadian IMAX film (It was even brought back for a short engagement before the Cinesphere was closed in 2011 to accommodate the makeover of Ontario Place). It was quickly followed by Catch the Sun, a patch work of wry sensations including a roller coaster ride and a trip over Niagara Falls accompanied by a storming Stompin' Tom Connors sound track.

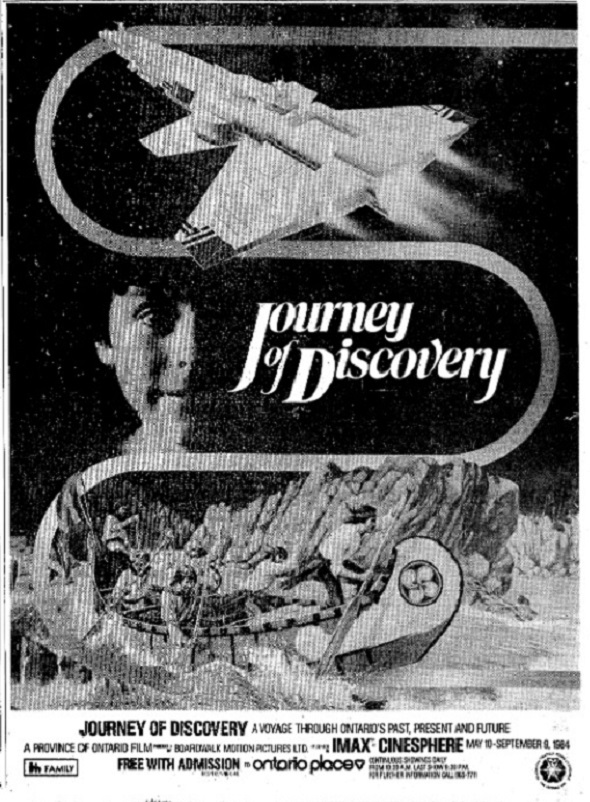

IMAX Domes and installations soon began popping up around the world, while the Cinesphere continued to screen a variety of exclusive IMAX films throughout the 1970s and 80s, including mostly forgotten Ontario-centric curios like Snow Job and Journey of Discovery. Questions about the sustainability of the format persisted to dog the original team.

According to Ferguson: "we were told that IMAX features would be impossible because nobody could stand the intensity of the medium for 90 minutes. In order to answer that, we made successful feature films on the Rolling Stones (The Rolling Stones: Live at the Max (1991), an 85-minute compilation of concert footage filmed in IMAX during the band's 1990 Steel Wheels tour) and the Titanic."

"The financiers were unconvinced; we still hadn't demonstrated that IMAX was suitable for drama. The company then invented a method of converting Hollywood features".

Warner Bros. embraced the format and after successfully up-scaling the Harry Potter series and releasing titles such as The Polar Express in IMAX 3D, the expansion of IMAX theatres was able to continue, finally attaining their true financial potential with the release of James Cameron's Avatar in IMAX 3D.

While there is yet to be a blockbuster filmed entirely in IMAX, wunderkind director Christoper Nolan has shot portions of The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises using the gigantic cameras to capture the epic scale of his Batman universe.

Nolan's science-fiction masterpiece Interstellar arrived on Blu-ray and DVD this week. Starring Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and Jessica Chastain, Interstellar tells the story a team of astronauts in search of other habitable planets as a dying Earth gasps towards its fast-approaching end date.

Again Nolan saw fit to utilize IMAX camera for portions of the action, including alien planets composed of water and ice (see: Miller's planet and Mann's planet). Filming these landscapes on IMAX in Greenland, one cannot help but draw parallels to Graeme Ferguson's original envisioning of the format.

While the up-scaling technique and exhibition of non-IMAX films in the IMAX format may contain a whiff of cynical profit motive behind them, its proper use by directors like Nolan certainly fits the original revelation of the format.

IMAX films should deal with sensations rather than ideas, and while there may be some gigantic ideas in Interstellar (everything from NASA to the theories of physicist Kip Thorne to worn melodramatic Hollywood tropes) it's the off-world sensations that ultimately define if the experience is successful.

In the mid-1970s Graeme Ferguson said "The subject of the quandary of Canadian cinema is meaningless to me. What quandary? I don't see any. All I see is the hopeless struggle to make American films on the cheap, which we expect to compete successfully in the U.S market. A crazy proposition, no wonder it fails. But there is no shortage of demand for Canada's futuristic cinema."

IMAX might have conquered the world, but its homegrown Toronto roots remain hidden underground to all but the most die-hard cinephile. Never mind the cultural black-hole which has enveloped most of the key Expo'67 films that led to its creation, where are the accessible copies of North of Superior (not the horribly pixelated postage stamp sized file on YouTube), Catch the Sun, Snow Job or Journey of Discovery?

In addition to losing the original IMAX theatre at Ontario Place, we seem to have lost sight of the films and their amazing stories too.

Sadly, Canada seems to have long ago surrendered not only fictional storytelling to Hollywood, but also to the act of commercially exploiting its own pioneering filmic heritage.

Interstellar is available now on Blu-Ray/DVD/Digital HD combo pack.

Retrontario plumbs the seedy depths of Toronto flea markets, flooded basements, thrift shops and garage sales, mining old VHS and Betamax tapes that less than often contain incredible moments of history that were accidentally recorded but somehow survived the ravages of time. You can find more amazing discoveries at www.retrontario.com.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments