Toronto punk squalor immortalized in beautiful book

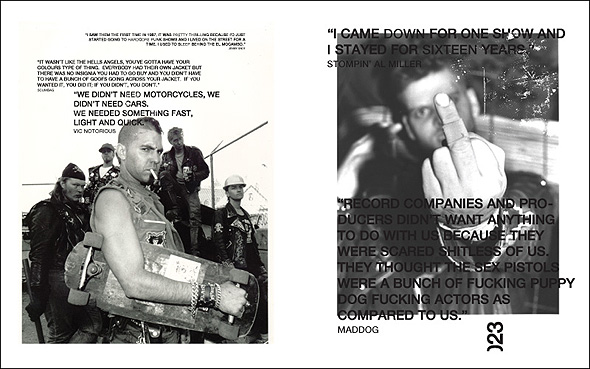

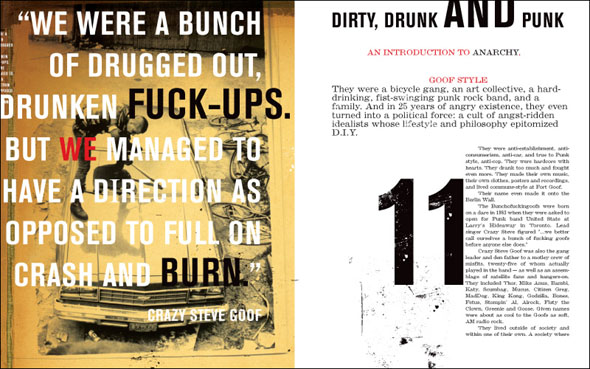

The wonder isn't just that somebody wrote a book about the Bunchofuckingoofs, probably the most unglamourous and confrontational product of the city's punk scene. Frankly, it would have happened eventually, if only because there's such a good story behind the squalor and occasional violence that typified the band's nearly two-decade reign as the clown princes and junkyard dogs of Kensington Market. The wonder is that Jennifer Morton's book, Dirty, Drunk And Punk, is such a handsome, coffee table-worthy volume, setting the Goofs' grimy antics in a gilded frame.

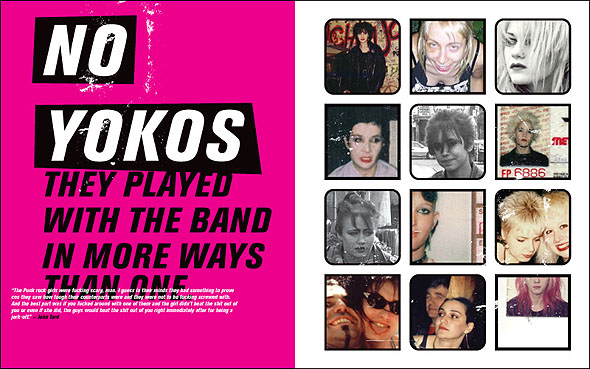

Morton was a producer at The New Music when she filmed the BFG at Fort Goof in the late '80s - actually the second of two bunker-like refuges and after-hour booze cans the Goofs built for themselves in the Market, during the heyday of their infamy as downtown's most visible proponents of the punk lifestyle. Behind the leather and chains and circling pack of mongrels, she was impressed by the group's scruffy creativity, and the charisma of their leader, "Crazy Steve" Goof.

"I really do think they're the punk version of the Andy Warhol factory, because they actually were productive," Morton recalls while sitting at a Market lunch stand, midway between where the two Forts once stood. "They made their own t-shirts and flyers for the band, they made their own clothes, they ran the booze can. They got a lot done, they made their own politics and had their own rules and regulations about how the place would operate - it wasn't clean, but it functioned."

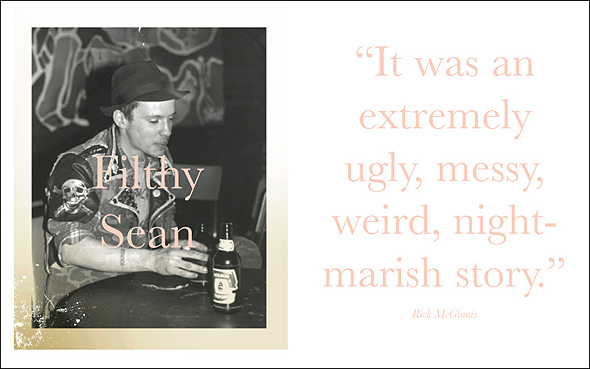

While it's wildly improbable that there's a huge audience for a book about an obscure Toronto hardcore band that was virtually quarantined by the mainstream music industry, that doesn't explain the appeal - and the focus - of Morton's book. Hardly the best punk band Toronto ever produced - they might not even be the best band to come out of the Market - the Goofs story documented in Dirty, Drunk and Punk is a wild, compelling social history, populated with indelible characters with names like Thor and Godzilla, Bambi, Fetus and Filthy Sean.

"I'm hoping that when you look at the book you'll think: 'Is this fiction or non-fiction?'" Morton says. "I hope that's what draws people in, because it is a fascinating story, with people like Filthy Sean, who kills his parents and goes to jail then gets the inheritance to start the recording studio. I mean, is that for real? The stories - and they like to tell their stories, like about the guy who got hung because he didn't learn his lesson - the more blood, the more craziness, the more they were dying to tell. They're very proud of how they treated each other, and behaved and lived."

The lavish design by Bill Douglas was essential, Morton tells me. "People outside the scene can't understand it without the visual backing." The story itself is told with a few first-person recollections by Johnston and others, some narrative and reportage by Morton, and a lot of oral history provided by band members, ex-girlfriends, friends, fans and hangers-on. (In the interest of full disclosure, I'm one of the interview subjects quoted in the book.) The lion's share of the graphic material was provided by Crazy Steve, who managed, despite the almost constant chaos of Fort Goof life, to build an impressive archive of photos, posters, clippings, set lists, t-shirts and eviction notices.

For his part, Steve is as shocked as anyone else at the reality of a book. "I wasn't really paying attention. Well, of course I was paying attention - I was being interviewed and I was giving them stuff to make the book, but there's a million things that are supposed to happen that get to different stages, right? I left the country twice since it started for at least five months, so I wasn't paying any really serious attention to it at all. And then all of a sudden Jennifer phones me up and hands me a book, and I'm, like, 'Wow. It's really a book.'"

When he's not escaping winter in places like India or Thailand, Steve can still be found in the Market, but he acknowledges that it's changed a lot. "At six o'clock everything closed and people shut down and locked it all up and left. And the only thing that was left was the Greek's and us, and we'd do whatever we wanted on the streets all night. You could set bombs off and nobody would call the cops because nobody was here to call the cops. Now this is what Yonge Street used to be like in 1977 - at 2 in the morning there's 150, 200 people walking around the street. The same street where fifteen, twenty years ago the same people would never dare walk at night. They'd be terrified."

Steve laughs. "Now they think they own the place."

While Morton says that tracking down interviews for the book was difficult - onetime Goofs and ex-punks having gone straight, gone to prison, moved to the suburbs or gone to ground - Steve himself seems to have barely changed - or aged. And he still lives with the same austere code that typified the Goofs. "I come back from India and friends say to me 'Oh, my welfare cheque didn't come on time. Life's so horrible.' I say, 'Oh really - three days ago I saw a guy with no arms and legs dragging himself down the street. He had pieces of fucking truck tire roped to his stumps and a pair of mismatched flip-flops for gloves because he had no fingers to hold onto them and was dragging himself down the sidewalk. You didn't get your cheque. Sucks, eh?'"

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments